In anticipation of more Ukrainian-language dubbing contracts, film distributors are already planning to invest in the expansion of their sound facilities.

Nearly a year since its first attempt to bring Ukrainian language into the nation’s cinemas, the government has announced an agreement with most distributors that will introduce more imported films in the country’s official state language.

In anticipation of more Ukrainian-language dubbing contracts, film distributors are already planning to invest in the expansion of their sound facilities.

A voluntary memorandum signed on Jan. 22 by the Culture Ministry, film distributors and cinema chains stipulates that by the end of 2007 at least half of the movies shown in the country will be dubbed or subtitled into Ukrainian.

Each movie released in Ukraine will have to have an equal number of Russian and Ukrainian copies.

By the same deadline, all children’s movies will have to be in Ukrainian.

Dubbing opportunity

Seeing the market potential, Ukrainian and foreign companies are hurrying to capitalize on the expected demand for Ukrainian dubbing.

Polish native Bohdan Batruch, CEO and owner of B&H, an official distributor of United International Pictures, Paramount, Dreamworks, Walt Disney and other Hollywood majors, said the increased demand for Ukrainian-language dubbed movies in cinemas will bring down the cost of dubbing.

Batruch said his company currently has to use highly overpriced Ukrainian studios to record the voices of local actors, which then have to be sent to European studios for mixing with the soundtrack in the Dolby format.

But with more contracts for Ukrainian-language dubbing, he plans to launch his own sound-studio and thus cut such costs.

But with more contracts for Ukrainian-language dubbing, he plans to launch his own sound-studio and thus cut such costs.

B&H plans to invest up to $2 million into new dubbing facilities. Batruch expects the new facilities to decrease dubbing expenses by two thirds.

Batruch said that the dubbing of a single movie into Ukrainian could cost up to $60,000. He plans to open his new sound mixing facility, which will also accept orders from other distributors, in June.

Hanna Chmil, the head of Ukraine’s State Cinematography Service, said the state also plans to get in on the new business opportunity, investing $2 million into modern copy making equipment that meet the standards of modern cinemas.

St. Petersburg-based Nevafilm, a company that possesses one of the largest dubbing studios in Russia and which started dubbing into Ukrainian last year, also plans to open its own recording facility in Kyiv. Nevafilm will keep its Dolby sound mixing facility in St. Petersburg, however.

Nevafilm development director Tatiana Gasevskaya said the move is more about new market potential than high prices charged by Ukrainian studios’ services.

“We constantly have orders for Ukrainian dubbing,” she said.

Gasevskaya added that it is still premature to say whether opening a full cycle facility in Ukraine would be economically viable option for Nevafilm.

“The Ukrainian government is well-known for changing its decisions on very short notice, so no one knows for how long the new quotas will be in place.”

The language games

The new quotas will not affect Russian-made movies or so-called art-house movies, made by European, American or Asian independent film studios. Such movies are usually released in small numbers.

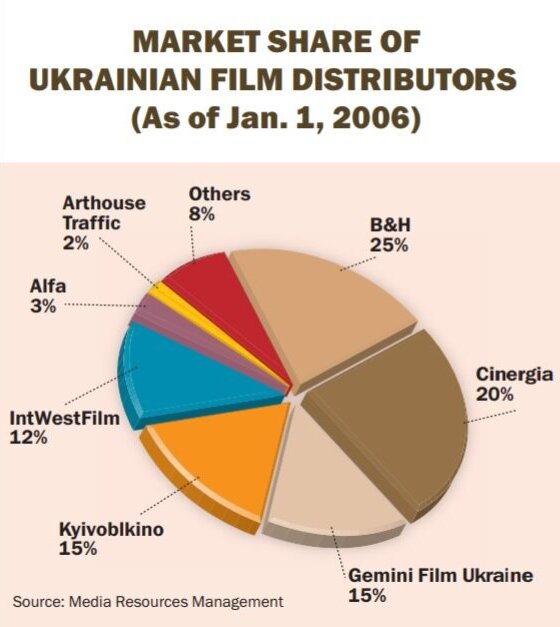

According to the Culture Ministry, distribution companies controlling up to 90 percent of Ukraine’s market signed the recent memorandum.

The government’s last attempt to introduce quotas for the Ukrainian language in the film industry back in January 2006 failed. The decision was cancelled by a Kyiv court several months later.

The Law on Cinematography, passed in 1998, requires all films shown in Ukraine to be either 100 percent dubbed into the state language or edited with subtitling in Ukrainian. The law has been largely ignored by the market, however.

Chmil described the memorandum as a “compromise” between the state and the film industry. It will allow the latter to gradually switch over to expected full Ukrainian dubbing, she added.

Batruch, who also operates Ukraine’s largest cinema chain, Kinopalats, boasting 14 venues, said the new memorandum simply reflects the real situation on the market. Movies in Ukrainian already gross more than the same titles with the Russian dubbing, he said.

The Ukrainian dubbing of “Deja Vue,” one of the most recent titles distributed by B&H, grossed $245,000 nationwide, compared to box office draws of only $155,000 for the Russian-language version during the same timeframe, he added.

Batruch said that the difference is even more striking when it comes to children’s movies. For example, he said, “Charlotte’s Web” grossed $212,000 in Ukrainian and only $77,000 in Russian, despite having virtually the same number of copies released in Ukrainian and Russian.

“It is a myth that Ukrainians wouldn’t want to watch a movie in Ukrainian,” Batruch said, as the country’s secondary and higher education systems are predominantly in Ukrainian. Soviet leaders pushed hard to establish Russian as the predominate language in Ukraine and other Soviet republics. It was the language used in education and other important venues. Usage of Ukrainian was rare in the country’s capital Kyiv during Soviet days, for example. Many in the capital didn’t even understand Ukrainian.But now, “there is a new generation of moviegoers who would hardly notice any difference,” Batruch added.