Artist Mykhailo Andriyenko-Nechytailo, better known in France as Michel Andreenko, was one of the great Ukrainian modernists who lived and worked in Paris between 1923 and 1982.

Indeed, independent scholar Vita Susak’s magisterial monograph “Ukrainian Artists in Paris 1900-1939” begins the second part of her oeuvre “The Second Wave: The Crazy Twenties” (the first wave being from 1900 to 1918) with an overview of four prominent artists of this period: Alexis Hryshchenko, Vasyl Khmeliuk, Mykola Hlushchenko, and Michel Andreenko.

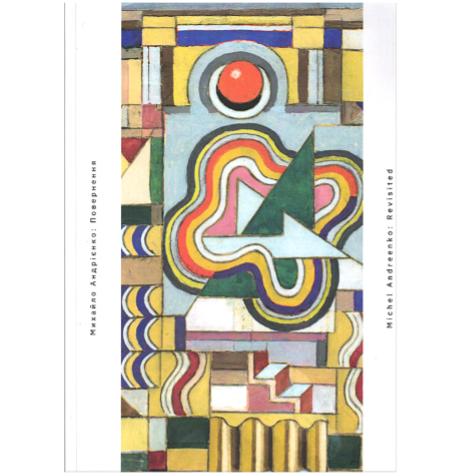

Between June 18 and Sep. 25 this year, the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art (UIMA) in Chicago is devoting its entire exhibit to the works of Andreenko. Titled “Michel Andreenko: Revisited,” it features 50 of the artist’s paintings from the splendid collection of Drs. Alexandra and Andrew Ilkiw of Highland Park, Illinois.

Over the years, the Ilkiws have amassed some 97 of Andreenko’s paintings, gouaches, watercolors, and prints, in addition to over 250 preparatory sketches and documents spanning the artist’s creative life in Paris.

UIMA’s exhibition is the second showing of Andreenko’s works – the first being in 1979. That was the year I relocated from Chicago to Paris, where I developed a strong interest in Ukrainian Parisian artists. So, on a visit to Chicago in June, I made it a point to visit UIMA, one of the anchor institutions in the Ukrainian Village where I grew up in the 1950s and 1960s.

Discovering Andreenko

In Paris, I discovered Andreenko through people who knew him. Among them were collectors such as Volodymyr Popovych, his daughter Irena, and the musicologist Professor Aristid Virsta.

Andreenko was born in 1894 into a noble Ukrainian family and raised in the southern city of Kherson – currently an area of intense fighting between Russian and Ukrainian forces. His life’s journey took him from Kherson to St Petersburg where he studied stage design and graduated from St Petersburg State University.

Revolutionary events, however, precipitated his return to Kherson. After a year in Odesa, he illegally crossed the frozen Dnister River into Romania and arrived in Kishinev (now Chisinau) in Moldova. From there, he continued to Bucharest, Prague, and in 1923 arrived in Paris, where he lived and created until his death in 1982.

Andreenko painted in a variety of styles reflecting the period of his time – first in the cubist-constructivist manner, then, in the 1930s, neo-surrealism. His work was characterized by a precision of composition that harmonized subtly with a gradation of colors.

In the 1940s, Andreenko switched to neo-realism and painted a number of portraits and cityscapes he called “Disappearing Paris.” Finally, in 1958, the artist returned to a non-representational abstract style. He also dabbled in collage using materials as diverse as sandpaper, texture paint and cork chips – a mode in which he painted until he died in 1982.

Having lived in Paris during the 1980s, I was attracted to the UIMA exhibit’s charcoal and crayon drawings of Paris street scenes. Among them, I found two small oil gems – The Street Fair” (1950) with the Eiffel tower in the background, and the “Cathedral of Chartres”, a place I visited many times. Some of the charcoal drawings, however, lacked a date and descriptions of the scenes depicted, making it difficult to follow the artist’s evolution over the years.

In Paris, Andreenko exhibited extensively in such prestigious venues as the Salon d’Automne and Salon des Independants, as well as numerous private galleries. One of these was the Gallery 22, at 22 rue Bonaparte, where he had a solo exhibit on June 27, 1974. By a most unusual coincidence, the gallery was not far from Café Bonaparte on the north end of the legendary Place Saint Germain des Pres – a square the existentialists dubbed the “bellybutton of the world.” This factoid had a special meaning for me because Café Bonaparte was a popular Sunday afternoon gathering place for Ukrainian artists, dissidents, intellectuals, and scholars during the 1980s and 1990s.

Important sense of Ukrainian identity

Andreenko occupies a distinct place in the Ukrainian section of the avant-garde school of Paris. Curiously, he lived like a recluse, especially in his later years when many of his friends departed. He seemed uninterested in fame and fortune, and like Hryshchenko and Khmeliuk, he never obtained French citizenship.

He remained a Ukrainian and carefully guarded his Ukrainian identity. When approached by a Russian cultural official in Paris asking him to be a spokesman for Russian artists in Paris – aware of the pattern of subsuming Ukrainian accomplishments and identity under a Russian cultural lens during the Soviet times – he declined and was told his place in history would disappear.

On the contrary, thanks to the efforts of collectors and art connoisseurs such as the Ilkiws, Susak, Popovych, Virsta, and others, he did not disappear and his place in history is solidly assured. In this, the Ilkiws fulfilled the artist’s wish that his works be collected and exhibited by Ukrainian diaspora expatriates living in the West.

Even though I arrived in Paris in 1979, I never had the good fortune of meeting the great artist. He was in declining health and was not seeing visitors. My first encounter with his art was through Virsta, an avid collector of Ukrainian modernists and other painters. In fact, he persuaded me to purchase one of Andreenko’s unnumbered lithographs (below) displayed at UIMA.

Today, his works can be found in museums in Vienna, London, Paris, and Rome, as well as private collections such as those of the Ilkiws in Chicago.

UIMA’s exhibit “Michel Andreenko: Revisited” offers a rare opportunity to become familiar with the creations of this renowned Ukrainian modernist painter. The exhibit is open until Sep. 25.

Jaroslaw Martyniuk is a former energy and environmental economist with the International Energy Agency (IEA)/Organization for Economic Cooperation and Developed Countries (OECD) in Paris. He is also a retired researcher associated with Radio Liberty in Munich and Washington D.C., and the author of “Monte Rosa: Memoir of an Accidental Spy.”

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily of Kyiv Post.