The sight of a car with a number plate from another city of country in front of you is a reason for most Ukrainian drivers to get worried. You won’t trust the driver of that “alien” car; they are unlikely to know the city. They’ll be nervous and may not notice traffic signs and might create dangerous situations.

In Soviet times, Kyiv drivers were afraid of drivers from the village. Rural drivers entering Kyiv drove slowly and sometimes made strange maneuvers. But that was back in distant Soviet times.

This type of village driver is now only a memory, but they were followed by other waves of “foreign” drivers, forcing the people of Kyiv to tense up. Not so long ago, Kyiv was “occupied” by thousands of old cars with Lithuanian and Polish license plates. They were mostly being driven by Kyiv residents who had imported these European cars illegally and did not want to pay taxes on their registration.

In 2014-2015, the roads of Kyiv were flooded with many expensive cars with Donetsk license plates. A little bit later, cheaper cars with Donetsk number plates appeared in the capital.

At first the richer drivers drove without paying any attention to the rules and showing no respect for others. The driving style of people in cheaper cars did not differ much from that of Kyiv drivers. Over time, everyone began to drive more or less normally again, although there are still a lot of cars with Donetsk license plates in Kyiv. This means that there are still many migrants from Donetsk and Luhansk, from the East of Ukraine in Kyiv.

There are also settlers from Crimea, mostly Crimean Tatars. But you will not see cars with Crimean number plates in the city. Refugees and migrants from Crimea travelled light when they came to Kyiv, and without cars. There are far fewer of them than Internally Displaced Persons from Donbas, but they are much more visible.

Not only because they are Muslims. While former residents of Donbas try not to draw attention to themselves, Crimean Tatars do quite the opposite. They live more openly, they express themselves and welcome any interest in their history and culture. They’re trying to create a virtual Crimea around themselves because they yearn for the peninsula and follow everything that happens there very closely.

From Kyiv they try to support families of repressed Crimean Tatar activists. Collect money for them, send medicines. They constantly receive relatives from Crimea in Kyiv. They are trying to help young Crimean Tatars enter Ukrainian universities. They do a lot more besides. They set up Crimean Tatar cafes or become regular visitors to those Crimean Tatars cafes that are already trading.

Musafir has been the most famous Crimean establishment for several years. It’s good, but I am much more attracted to the small Cheburek place on 20 Pushkinska, near the Russian Drama Theater. While you’re in Cheburek, you’ll enjoy the traditional deep-fried pasties, you can always chat to the owner Erfan Kudusov, who abandoned both his house and his business in Crimea immediately after annexation.

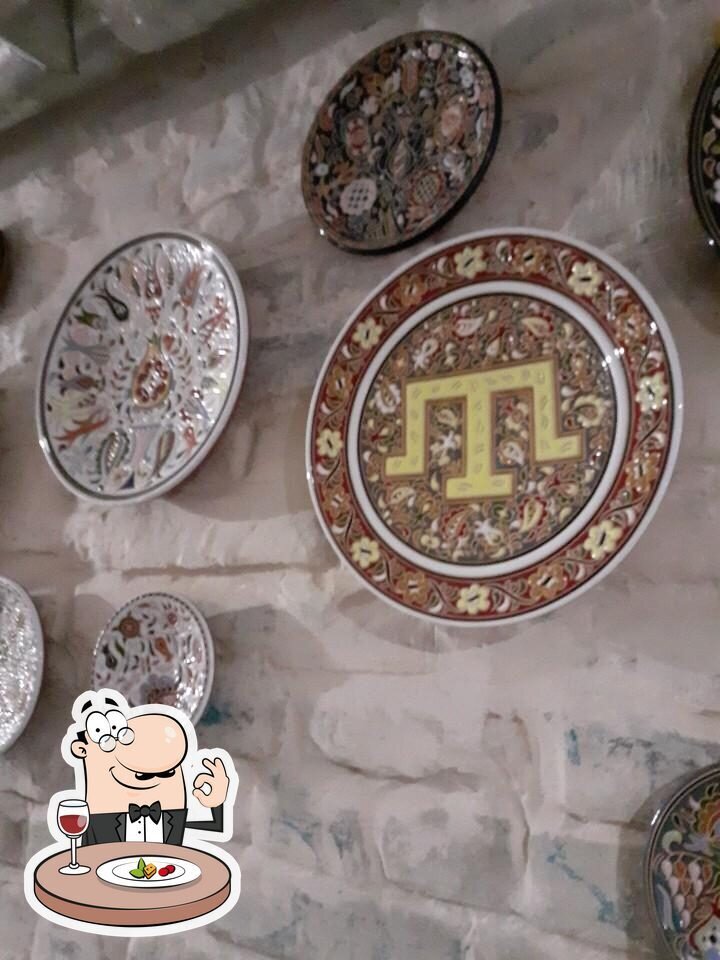

His café is a bit like an English double-decker bus, with the bottom floor in the basement. It immediately became a club for lovers of Crimean Tatar culture and, at the same time, the epicenter of the fight against the Russian annexation of Crimea. ATO and OOS Veterans from various cities hold meetings here and works by Crimean Tatar artists and Ukrainian photographers are constantly on display.

It is almost impossible for Crimean artists to transport their paintings to Ukraine. Difficulties arise both on the Russian side and on the Ukrainian side, though Ukrainian border guards tend to be more flexible.

From Ukraine’s point of view, the main problem is that people entering the mainland from Crimea might be vaccinated with the Sputnik vaccine produced by Russia, which is not recognized in Ukraine or Europe. Once they are on Ukrainian territory, they are vaccinated with generally recognized vaccines and the next time they come into Ukraine that will be one less thing to worry about.

Russian border guards and customs officers demand to see special permits for the export of artwork. Annexed Crimea is now de facto part of the Southern Federal District of the Russian Federation. The administrative center of the district is Rostov-on-Don. This means that artists who want to take their works out of Crimea must take their paintings there and receive a certificate from the local department of culture stating that their works have no artistic value.

With this certificate, paintings can be taken out of the territory of annexed Crimea. The artists must then return to Crimea and enter Ukraine. Artists who have made this complicated journey many times sometimes get to know Russian officials in Rostov-on-Don and are allowed to apply for certificates remotely via email. They send photos of paintings and receive certificates for export. However, there have been practically no official exhibitions by Crimean Tatar artists in Ukraine, if you don’t include the occasional small exhibitions held in Crimean Tatar cafes like Cheburek.

The political activism of Crimean Tatars extends not only to the issues of annexed Crimea or Donbas. Erfan Kudusov recently recorded a video calling on Kazakhs to overthrow the Tokayev government. This was followed by a series of events that would certainly have interested the late author John Le Carré.

A couple of weeks after the video had got to almost 100,000 views on YouTube, an elderly gentleman showed up at Erfan’s café. He was a very specific-looking Kazakh with gold teeth and manicured nails. He started to visit the café almost every day. He made friends with Erfan and begged him to go with him, at his expense, on holiday to Singapore or Dubai.

Erfan was not going to go anywhere with him, but the elderly Kazakh kept asking. Then Erfan asked a policeman acquaintance to follow the strange visitor. This experienced policeman later reported that the Kazakh had very quickly noticed that he was being followed and that had been able to ‘lose’ his tail very professionally. Erfan searched the Internet for information about this visitor who kept trying to become his friend. He found only one mention of him in the newspaper Krasnaya Zvezda (Red Star), the official paper of the Ministry of Defense of the Russian Federation.

At some point, the Kazakh disappeared and did not re-appear. But he left behind an aftertaste reminiscent of Cold War spy movies. Now Erfan shows his friends footage of this Kazakh captured on the café’s CCTV. I think we should enlarge a still of this suspicious visitor and hang it in a frame on the wall there, next to photos from the Donbas.

We are living at a time of total war. What happened in Kazakhstan is connected with the Russian Federation, with Ukraine, and with Crimean Tatars, many of whom grew up there after their parents and grandparents were deported from Crimea in 1944.