If you can’t answer that, you’re not likely to get very far or, in fact, anywhere at all.

Of course, conditions can change and very quickly, so the question is a fluid one. A highly competitive approach ten years ago might not be viable today and companies that are barley five years old are commanding valuations in the billions.

That’s why there’s so much talk about business models. Somebody claims to have new one, while another says that an old one is defunct. But what is a business model really? As innovation researcher Tim Kastelle points out, there a multitude of definitions representing different points of view. That can be confusing. It’s time to clear things up.

An insight

In essence, a business model is an idea about why people will pay more than it costs you to produce a product or service. Most business models are run of the mill, like a deli owner who simply believes that people will pay extra for someone to make their lunch for them, but others as truly innovative.

For instance, Henry Ford realized that by using an assembly line to manufacture cars, he could take a very niche product, a curiosity really, and make it into a product for the masses. Lou Gerstner transformed IBM’s diverse product line into a powerful consulting model. More recently, the Google guys realized that the same logic that conveys authority is an academic setting could create a better search engine.

Sometimes, the innovation isn’t about the product itself, but merely the way it’s sold. Tim Kastelle gives a great example in the story of Xerox, where they failed when they tried to sell copiers but then when on to great success when they began leasing them.

A fully blown concept

Of course, Google didn’t make money with their insight about search engines, they just made a better search engine. They had no idea how to monetize it. First they tried licensing the product to sites that already had a big audience, like AOL, but that didn’t get them very far. Finally they hit on Overture’s idea about selling ads related to the results and struck it big.

In other words, a business model is a lot more than just a key insight (Jon Kleinberg of Cornell had an idea for a search engine that was very similar and, some believe, superior to Google’s concept, but it never really gained traction). You need to also figure out the mundane stuff, like how much your product will cost to make, who you’ll sell it to and so on.

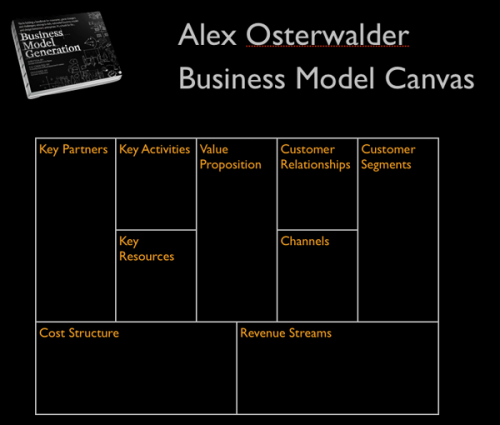

There are a lot of ideas how to do this. Kastelle gives examples of eight types of business models on his site. One of the best is the Business Model Canvas by Alex Osterwalder.

However, even after you have all that figured out, you still need to get some idea if your business will be steady for years, grow very quickly or whether it’s likely to decline over time. For that, you’ll need more than just clever ideas, you’ll need to plug in some numbers.

A set of assumptions

A business model is essentially forward looking, if it’s not, then it’s a financial statement. Most financial models are done with a five year outlook, so there’s a fair amount of guesswork involved. While an Excel workbook full of numbers may look concrete, it’s really just a set of assumptions.

That’s fairly obvious with a start-up, but it’s also true of an established business. As I’ve pointed out before, prediction is a tricky business, even if you have a wealth of data at your disposal. The past can’t be automatically extrapolated into the future.

And that’s where industries run into trouble. Clayton Christensen points out that disruptive innovations change business models because they render old assumptions about value impotent. They’re disruptive because they change the basis of competition.

An excuse

Business models, of course, don’t play out in Excel spreadsheets or PowerPoint decks but in the real world, where things are messy. As I explained in an earlier post, Blockbuster got themselves into a world of trouble not because they didn’t realize that things were changing, but because they failed to change key facets of their model.

Here’s where a well articulated and deeply ingrained business model can become a vulnerability. Long time employees become loyal to it, take comfort in it and become blind to possible flaws. They respond to new innovations by saying “that’s not our business model.”

In other words, a business model can become an excuse. Once it’s successful, it’s hard to argue with and hence hard to change even when, as in the case of Blockbuster and Kodak, the need for change is overwhelmingly obvious.

A benchmark

Most of all, a business model is a mental model. It offers a theoretical construct of how management thinks a business can work. Much like the Constitution of a country, it is a philosophy as much as anything else and philosophies, to paraphrase Camus, are there to serve man and not the other way around.

In other words, they are means to an end, not an end in themselves and that’s where the confusion often arises. There’s no reason for people to favor one model over another unless it performs demonstrably better. A business model should never be mistaken for a business purpose.

So business models serve us best when used as benchmarks. They document our business concept so that we can test them in the marketplace. Inevitably, they will be off somewhat and will need to be jiggered, tweaked and sometimes transformed. They are not a set of commandments, but living documents that must evolve and adapt.

Greg Satell is a U.S.-based independent media analyst.You can read his blog entries at http://www.digitaltonto.com.