In a secret recording of Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma made public 20 years ago, his order to threaten and intimidate journalist Georgiy Gongadze set off a political crisis. It triggered calls for his resignation and started the “Ukraine Without Kuchma” movement.

The “Melnychenko tapes,” named after the presidential bodyguard who claimed to have recorded hundreds of hours of Kuchma conversations, revealed to Ukrainians exactly how politics is conducted in their country.

But the tapes revealed much more than Kuchma’s loathing for journalists who dared to criticize him during his authoritarian rule from 1994–2005.

In a more obscure episode of the tapes, Kuchma allegedly discussed Ukraine’s supply of the Kolchuga system, a passive target-detection radar, to Iraq in violation of United Nations sanctions. Although no evidence was found, the disclosure severely damaged Ukraine’s relations with the U.S. and the U.K. — so much so that, during the 2002 NATO summit in Prague, the seats for the 28 member states and other partner countries were arranged not according to the English alphabet, but according to the French one. That was to ensure that the unpopular Kuchma didn’t sit next to U. S. President George W. Bush and British Prime Minister Tony Blair.

But few remember another episode of those secret recordings from Kuchma’s office.

In a conversation from 2000, Kuchma was talking to Viktor Yanukovych, the then-governor of Donetsk Oblast who later became the president of Ukraine.

Kuchma was outraged by the behavior of one of the local judges in Donetsk. The judge was reluctant to prosecute a local man who, on the day of the presidential election in October 1999, allegedly distributed copies of a fake newspaper in Donetsk that claimed that Kuchma had died and the country was ruled by a doppelgänger.

According to the audio recordings, Kuchma demanded that Yanukovych pressure the judge: “Take this judge, such a dirtbag, hang him by the balls, let him hang one night…”

It is unclear whether Yanukovych followed the order, but Kuchma got what he wanted. The man, a local lawyer named Serhiy Salov, was sentenced to five years in prison for distributing five copies of a fake newspaper. He later challenged his sentence in the European Court of Human Rights and won.

You might wonder why I am paying so much attention to this story from 20 years ago. The thing is, the judge whom Kuchma demanded to “hang by the balls,” and who eventually convicted Salov, is one of the most influential people in modern Ukraine.

This judge is Oleksandr Tupitsky, the head of the Constitutional Court. And the Constitutional Court itself in today’s Ukraine has become an inquisition that could burn all Ukraine’s achievements in battling corruption during recent years.

Dangerous court

The Constitutional Court has been making the news lately.

In August, the Constitutional Court ruled that the appointment of Artem Sytnyk as the head of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine, or NABU, was unlawful. A few weeks later, in September, the same court declared that some provisions of the legislation that regulates the NABU contradict the Constitution.

More is yet to come. The abolition of all anti-corruption infrastructure is on the way, as the Constitutional Court has started considering two new submissions.

The first aims to recognize the High Anti-Corruption Court as illegal.

The second is the recognition of all anti-corruption reform as illegal, including the law on illicit enrichment, passed under President Volodymyr Zelensky in 2019.

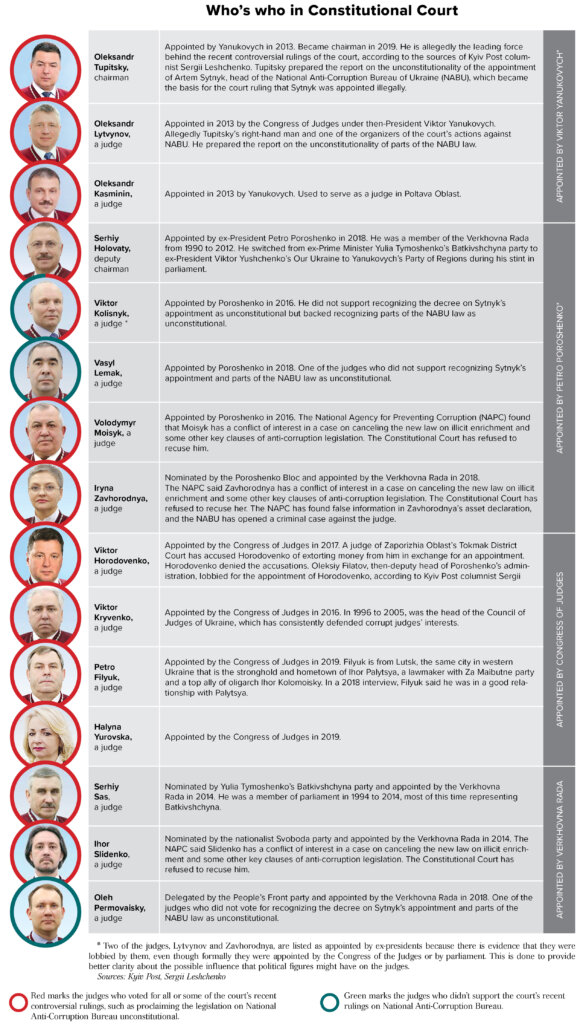

For many, the current Constitutional Court of Ukraine is terra incognita. Few people understand how its influence groups work and connect with the outside world. So I will try to shed some light on the issue.

The key actors in the current Constitutional Court are the chairman of the court Tupitsky and his deputy Oleksandr Lytvynov. They acted as NABU executioners because, as judges-rapporteurs, they wrote the texts of the decisions in the last two high-profile cases concerning NABU.

For the first time in the history of Ukraine, Tupitsky declared an individual action illegal — a decree appointing Artem Sytnyk director of NABU. Lytvynov wrote the text of the decision on the illegality of some provisions of the law regulating NABU.

Tupitsky and Lytvynov’s paths are inextricably linked with Yanukovych, who fled to Russia during the EuroMaidan Revolution on Feb. 22, 2014. For some time, they simultaneously worked as judges in the district courts of Donetsk, when the region was headed by Yanukovych.

Tupitsky was a judge in the Kuibyshevskyi District Court of Donetsk, while Lytvynov served in the Budyonnivskyi District Court. Lytvynov’s background is unusual for a Ukrainian judge: He is a graduate of the Far East Military Command Academy in Russia.

Turning the tables

Tupitsky and Lytvynov came to power in the Constitutional Court in May 2019 as a result of a silent revolution in the court that went unnoticed by the public.

According to my sources in the court, Tupitsky and Lytvynov rallied other judges and removed the previous chairman of the Constitutional Court, Stanyslav Shevchuk, a well-known scholar who had previously served as ad hoc judge of the European Court of Human Rights.

The members of the Constitutional Court who sided with Tupitsky and Lytvynov and helped them take charge of the court included the judges who appear to be influenced by former President Petro Poroshenko and one judge who is close to Ihor Palytsya, a lawmaker and political proxy of billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky. In addition, Tupitsky himself is rumored to have connections with criminal figures Yuriy Ivanushchenko, an ex-lawmaker nicknamed Yura Yenakiyevsky, and Ihor Kryvetsky, a Lviv businessman nicknamed Pups (“baby doll”).

Enter Vovk

And here we get to know the third master, who helped Tupitsky and Lytvynov come to power and now leads the puppets in the entire judicial system. This is the notorious chairman of the Kyiv District Administrative Court, Pavlo Vovk. His name is known far beyond Ukraine.

Now it’s time to explain why the situation in the Constitutional Court is so important right now. Because, in fact, a recently-formed core group of judges of the Constitutional Court are trying to destroy all the anti-corruption gains of recent years. The judges are doing this because their political protectors want it that way — and also because this is the only way for the judges themselves to escape prison.

It turned out that the whole story, including the dismissal of Shevchuk from the leadership of the Constitutional Court and the seizure of power by Tupitsky, was recorded by law enforcement. It is part of the NABU’s investigation into judge Vovk.

According to the so-called “Vovk tapes,” conversations of Vovk and his affiliates recorded by NABU in his office, Vovk helped to assemble the majority of votes for the uprising. And when Shevchuk was fired from the Constitutional Court, Vovk boasted to his subordinates that they now controlled the court.

In early September, NABU, having these records in its hands, summoned six judges of the Constitutional Court for questioning as part of the investigation of the Vovk tapes. This launched the court’s revenge scenario against NABU. Defending themselves from the criminal case, the judges of the Constitutional Court collected the majority of votes and declared Sytnyk’s appointment illegal.

But this created another problem for them — when voting for the ruling, the judges of the Constitutional Court didn’t declare their conflict of interest. After all, they were already involved in the NABU case against Vovk.

At this point, another anti-corruption body took interest in the court. The National Agency for Preventing Corruption (NAPC) launched an investigation into the fact that the judges did not report their conflict of interest in the ruling against Sytnyk.

But because these top judges created a system of covering up for each other, the investigation was stopped — by no one else than Vovk. When the NAPC subpoenaed documents from the Constitutional Court that they needed for the investigation, the judges went to Vovk’s court to challenge the subpoena. Of course, he blocked it.

Evidence of collusion

Now the Constitutional Court is trying to declare all the anti-corruption infrastructure built in recent years illegal.

At the same time, three judges of the Constitutional Court are already involved as witnesses in investigations into corruption.

But that’s not all. The destruction of NABU by the Constitutional Court is totally permeated with conflicts of interest.

One of the lawmakers whose appeal to the Constitutional Court led to it ruling Sytnyk’s appointment illegal was Antonina Slavytska, a lawmaker of the 44-member Opposition Platform faction. Her name is mentioned by Vovk in the NABU’s tapes. But who is Slavytska?

NABU said that one of the lawmakers who signed the scandalous appeal is in a “close personal relationship” with Vovk. According to my sources, this lawmaker is Slavytska, and she has a common child with the judge. In her income declaration, Slavytska mentions her child, but doesn’t list his patronymic, as if to conceal the child’s father. Vovk mentions her name in NABU’s tapes.

Besides, Slavytska publicly attacked Sytnyk in the media.

So, to put it simply, a Ukrainian lawmaker joined the effort to take down the anti-corruption agency that is investigating the father of her child — and all this without declaring her conflict of interest.

Anti-corruption infrastructure is one of Ukraine’s few accomplishments in the years since the EuroMaidan Revolution. It now faces systematic pressure from Tupitsky’s group in the Constitutional Court.

It is essential to stop this scenario. Tupitsky should not administer justice, but be brought to it. He has no moral right to preside over the highest court in Ukraine.