Until 2016 the wall of the electricity substation at 2A Gogolya Street in the center of Kharkiv, an industrial city of 2 million people some 477 kilometers east of Kyiv, was ordinary, dull and gray, and surrounded by rubbish bins.

But that was before a local street artist, Gamlet Zinkivskiy, dubbed the Kharkiv Banksy, made it the canvas for his artwork, and the focus of controversy. Like Banksy, Gamlet creates murals all over Ukraine in unexpected places.

He decorated the electricity substation wall with a painting of a man standing in the palm of a huge hand, along with caption: “I guess I’ve found myself… I hope I won’t lose him”

But some locals just didn’t get it – or want it. They put up with the artwork for two years but finally on Sept. 5 they daubed over the image with dark grey paint. The picture, they said, was “schizophrenic.”

What happened next to the wall in Kharkiv is an artistic metaphor, showing that, unlike the man in the mural, Ukraine is far from finding itself.

After the mural was painted over, every other night a new graffiti appeared on the freshly painted grey wall.

And the next morning, the locals would cover it up with the same grey paint.

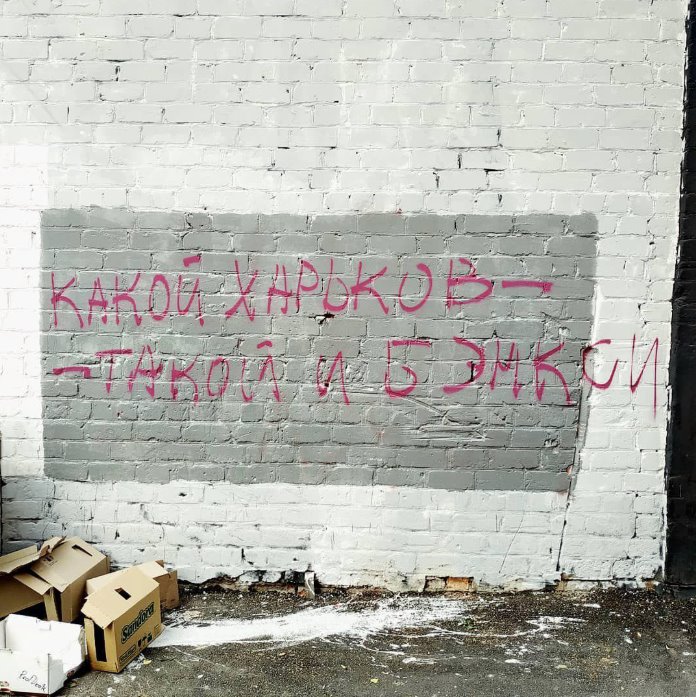

Zinkivskiy’s fans would paint offensive graffiti and even fake drug adds in the place of the mural, with captions asking the locals: “Does this look better to you?” or “This is the Banksy Kharkiv deserves.”

The messages pointed out that the streets of not only Kharkiv but most Ukrainian cities are covered with ugly graffiti. So every time a genuinely artistic mural appears, many Ukrainians, but especially the younger generation, welcome it.

In contrast, the older generation could meet the Kharkiv mural only with hostility. The ensuing battle of bright graffiti versus bland gray conformity is a microcosm of a battle between mindsets going on in Ukraine today, Zinkivskiy thinks.

He says the new, young and creative Ukraine is winning this fight with the old Ukraine with its Soviet mentality – everyone must be the same, and plain gray paint is better than something unusual and new.

“What happened to the wall was a great shock but also pleasant surprise for me,” Zinkivskiy told the Kyiv Post on Sept. 12. “This is the first time people have stood up for one of my works. Earlier dozens were covered the same way all across Kharkiv, and nobody really cared.”

Within a day, the Kharkiv wall had its own Instagram account and was dubbed “Stena Sracha” (the Wall of the Shitstorm). It got 6,000 subscribers in the first two days. As of Sept. 12, the wall account,wall_of_sratch.kharkiv, had 11,000 subscribers – even more than Zinkivsky’s own Instagram account.

Jesus appears

On Sept. 6, the night after “the man who found himself” was painted over, resident woke up to find it bearing an offensive message: “Huy. Does this look better to you?”

The word “huy” is a Russian swear word for penis, and seems to be the most popular word among those who want to make their mark on a wall in Ukraine.

The next morning the locals painted over the message with gray paint. But during the night on Sept. 7, someone wrote on the wall again, as if commenting on previous offensive inscription: “This is the Banksy Kharkiv deserves.”

Locals painted over that message too. But on Sept. 8 they got a new, more creative message – a big cartoon Jesus drawn on the wall.

“Are you going to paint over me as well?” Jesus asked in a speech bubble.

And this time the wall had been attacked by several artists at once. Someone also placed a fake drug slogan reading “Fly with us to find yourself,” referring to Zinkivskiy’s initial message.

And there were several drawings of penises.

Locals realized they needed backup, and called in the “heavy artillery” – the district utility department – to paint the wall gray again.

Even Jesus was not saved: by next morning he was obscured by a fresh coat of gray paint.

But Zinkivskiy’s fans weren’t beaten. The next night they drew another graffiti – a window with the caption “A window on a gray world.”

That was painted over as well. And bizarrely, the image of Jesus began to reappear – Shroud-of-Turin-style – from under the coat of gray paint that had obscured it.

“Jesus is with us. We are a protest for free art,” the graffiti creators then wrote in the comments section under a post on the Stena Sracha Instagram account.

Then things began to get ugly. More graffiti, less artistically appealing, started appearing on the wall.

“The wall wants a beautiful new tattoo, not these tattoo fails,” another user wrote.

It wasn’t long before the locals hit back. Utility service workers painted the wall again on Sept. 10.

The wall even got some security – three men appeared beside it, telling locals they were there “to check on the situation and prevent new acts of vandalism.” One of them even flashed a police ID. But after guarding the wall for a day, the men vanished.

Kharkiv police denied any of their officers had been guarding the wall.

And after the men disappeared, a series of abstract pictures were glued to the wall. For a day they remained untouched – it seemed peace had broken out.

But then new graffiti appeared.

Outside the box

Many Ukrainians have watched the battle for the wall online and been drawn into the bizarre art protest, seeing it as an illustration of the changes ongoing in Ukrainian society.

In Soviet times, it was considered dangerous to express too much individuality: there was a risk of being misunderstood by society, and in an authoritarian, totalitarian society that could draw unwelcome attention from the authorities.

It was safest to blend into the gray crowd.

While the older generation still resists breaks from conformity, and new attitudes and ideas, younger Ukrainians are not afraid of expressing their individuality, and see no need to. Tired of nearly two decades of living under post-Soviet semi-authoritarianism, the younger generation wants to be free.

Zinkivskiy now wants to end the battle of the wall by recreating his mural in the same place.

If it remains in place, and is not again swamped in gray, it might indicate that the new Ukraine is at last winning out against the old, and shaking off the fears of the past.