Globally, around one-third of all food produced for human consumption is wasted or lost before it can reach consumers. In Ukraine there is no official data on the problem, but it is believed to be of similar proportions, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

And that agency’s development program coordinator in Ukraine, Mykhailo Malkov, told the Kyiv Post that without reliable numbers, the country’s ability to tackle the issue is greatly diminished.

“One of the major gaps that I see is the establishment of the proper statistics gathering,” he said. “When you’re aware, then you can start to think about handling things.”

In Ukraine, food goes unconsumed owing to inefficiencies at all stages; from field to plate. At the level of production, losses occur through factors such as poor harvesting techniques and the use of outdated machinery. The problem is then compounded by a lack of proper storage facilities and poor logistics.

When food eventually reaches consumers, they too are guilty of waste. This can be down to things like items being thrown out unnecessarily because of confusion over expiry dates and “best before” dates on labels, or because restaurants serve portions that are simply too large for customers to manage.

Solutions, when they can be found in Ukraine, are being applied inconsistently and with varying degrees of success, says Malkov. What’s more, they more frequently come from the private sector, not government.

“Everyone is trying to develop their own approach, but there’s no clear system or standard for how it should be done,” he told the Kyiv Post.

The United Nations is ready to step in and offer guidance, but it is still waiting for an official request for help. The organization says what needs to be done is clear. “The first step is to identify the gaps at each step of the supply chain,” said Malkov. “Then we need to develop the technology and bring in the knowledge of what can be done to reduce losses and food waste, and we need to organize an awareness campaign together with civil society.”

Community outreach

There are already a number of actors in Ukraine doing what they can to minimize food waste. Among them is the activist network Go Dobro. Among their initiatives is a community refrigerator program. Refrigerators are placed on city streets so that anyone can leave an item or take something out.

“We feel inspired every day when we see how the refrigerators are working,” said Go Dobro’s Maksim Oboltus. “Slowly our friends and others who share our views are joining us. As a matter of principle we believe that no good deed is better than any other; everyone does as much as they can.”

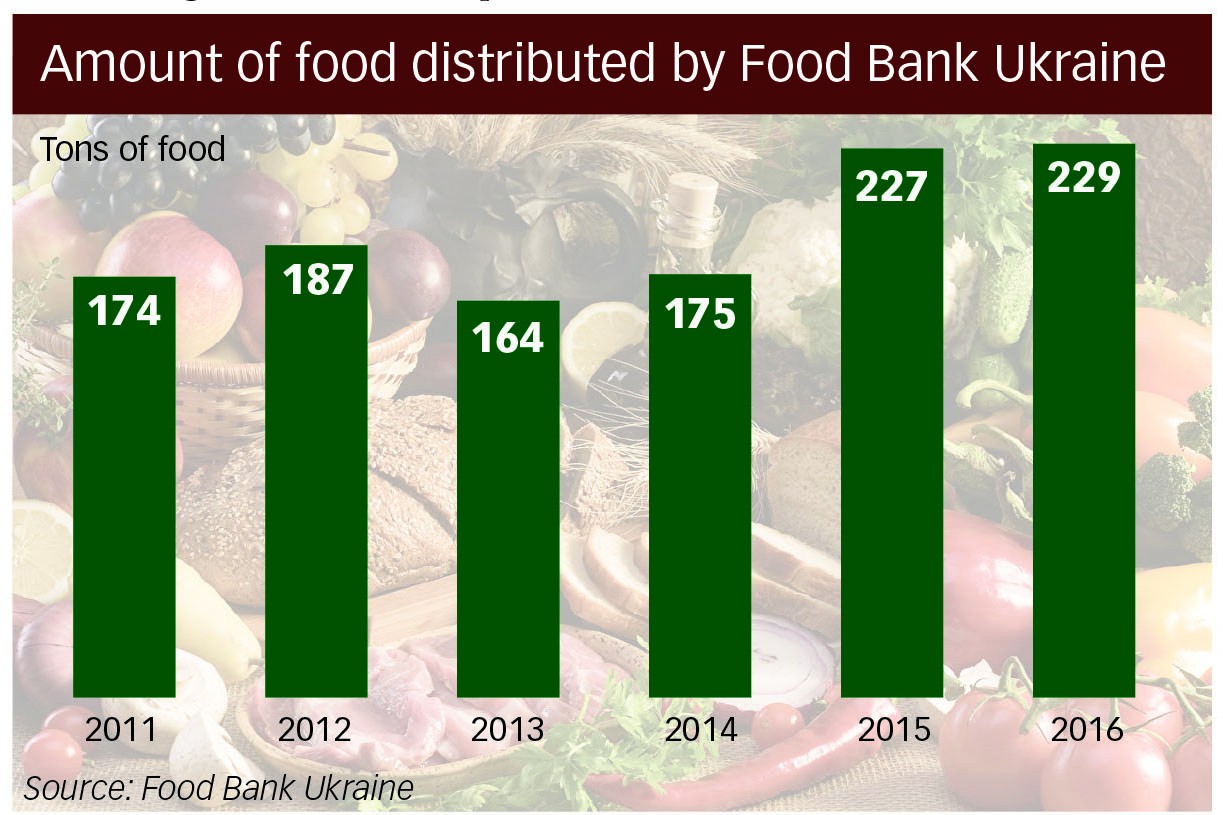

Meanwhile, further efforts at food redistribution are being made by Food Bank Ukraine, which receives donations of food which it then passes on to charities across the country so that they can be given to those in need. Last year 229 tons of food went through the organization, but board member Anna Kocheshkova says this is just a fraction of what the charity could do if it had more resources.

“I think we could multiply that number by five at least,” she told the Kyiv Post. “But of course we don’t have enough staff now to operate, and we would need to find the money.”

In 2016, Food Bank Ukraine distributed 55 million tons more than when it was founded in 2011. However, the organization says it needs even more food to meet demands.

Kocheshkova says the food bank does not get any help from the government and relies on volunteer efforts and private financial support. Further challenges arise when it comes to establishing cooperation with the suppliers of food, of which there are currently just eight on the food bank’s books, all of them multinationals. Earlier there were more but Ukraine’s tax system, which does not allow donations to be easily written off as expenses, means that for businesses it can be cheaper and easier to throw away excess produce rather than give it to the food bank.

“We’re always trying to encourage more producers and retailers to work with us,” said Kocheshkova.

“For them it’s not only that they can help society, but they also get economic benefits. They don’t have to pay for disposal or transportation to the disposal site. But for now the need for food is much greater than what we are able to provide.”

A global approach

Part of the support Food Bank Ukraine receives comes from the European Federation of Food Banks, an umbrella organization that counts 31 national food banks across the continent among its members. Its secretary general, Patrick Alix, says in countries like Ukraine, where food banking is still in its infancy, it is crucial to slowly build trust with potential donors in order to boost the availability of surplus food for redistribution to those who need it.

“There is a reputational risk for the donor,” Alix told the Kyiv Post. “Food banks have to be sure no one will resell the products they have received for free. In Ukraine there is a lot of suspicion, so we try to do it step-by-step. We tell the retailers to come and see how the food is handed out and to start a pilot program. It’s about mutual education.”

According to European Commission figures, around 55 million tons of edible food is thrown away in Europe annually, mostly by households. But some 23 million tons is also lost as it moves along the food chain. This includes during the manufacturing process or when it is sold in supermarkets or restaurants. With demand from those in need growing all the time, the European Federation of Food Banks is trying to reduce waste.

“My best guess right now is that we recover maybe 10 percent of the 23 million tons,” said Alix. “There is huge potential to recover more food. That’s why there are food banks. If there were no waste, there would be no food banks. We feed people by redistributing food that would otherwise be wasted.”

About Go Dobro

Who: Initially started by three friends, Go Dobro is a network of activists open to anyone who wishes to join.

What: The group has started a number of projects to tackle contemporary social issues including installing street fridges where anyone can leave or take food.

Where: Activities are currently mostly confined to Kyiv, but the group encourages participation from all over the world.

Why: Maksim Oboltus, one of the founders of Go Dobro, says the group’s fundamental principle is that no good deed is better than any other and everyone should do whatever they can to help.

Contacts: www.godobro.com