Want to buy an apartment in Kyiv but can’t get a mortgage?

“Go to a developer,” says Oleh Perehinets, a realtor at Kiev Standard.

And that might be the only option, aside from paying the entire selling price in cash — something most people can’t afford to do.

Mortgage lending in Ukraine has collapsed, making buying a house or apartment in Kyiv more expensive and more difficult than ever.

The market’s stopgap solution is for developers to make deals with trusted banks that allow them to loan money to new residents. With a 50 percent down payment, new owners can enter into a 10-year payment agreement at interest rates starting from 20 percent.

But there are problems: the market is unregulated and rife for abuse as lending decisions are often based more on personal ties than any standardized lending criteria.

Vasil Kisil and Partners attorney Alexander Borodkin talks in Kyiv on May 17. As banks are wary of restarting mortgages, many Kyivans turn to alternate financial arrangements to fund home purchases. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Developing nicely

Apart from a few banks who enacted Ponzi schemes that apparently involved fraudulent mortgage lending, the market has been all-but-dead since the 2008 financial crisis.

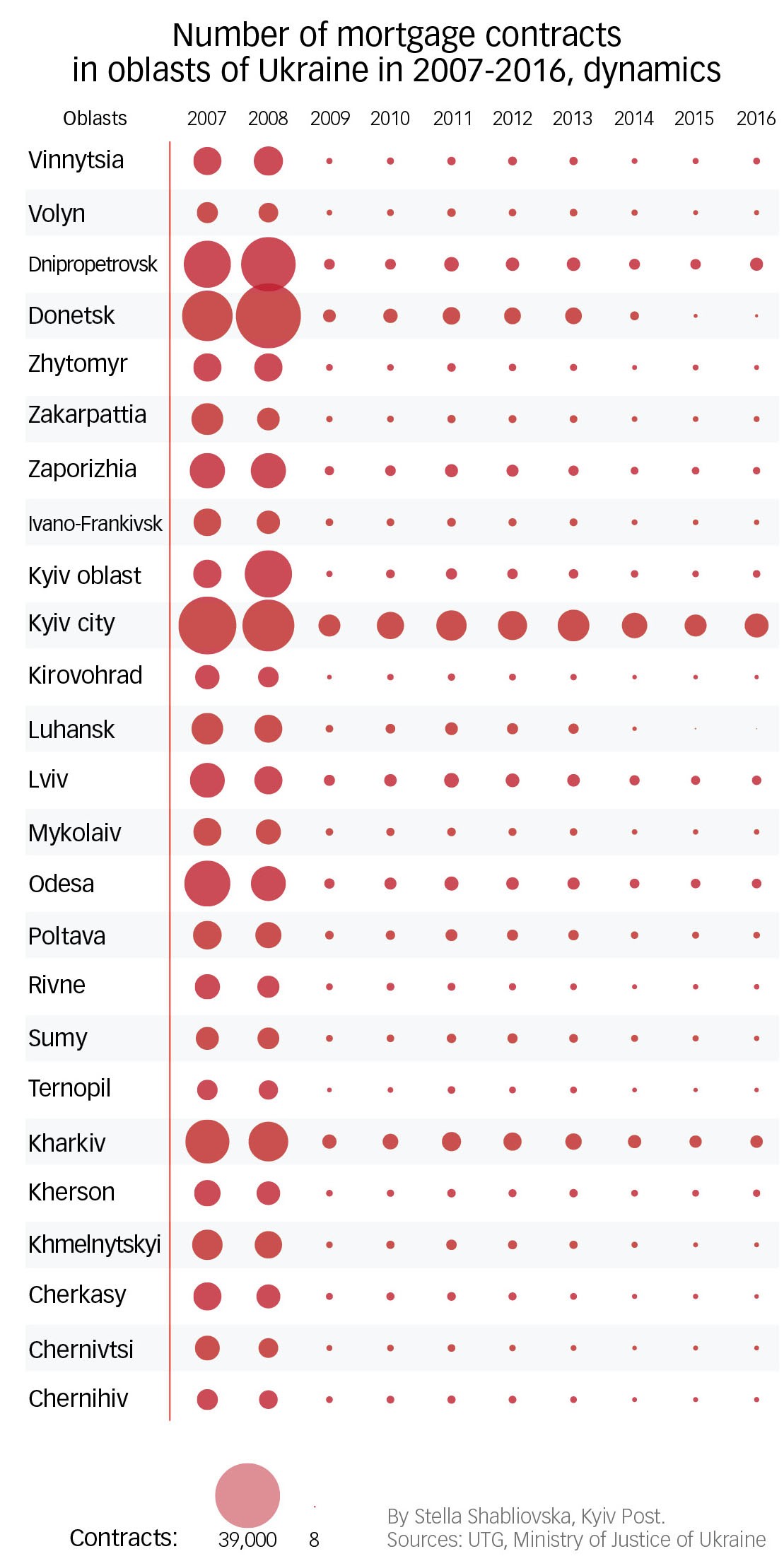

The number of mortgage contracts signed in 2007 plunged from 31,405 to 4,424 in 2009, according to Ukrainian Trade Guild, a housing consultant. And it hasn’t picked up since then.

Kyivans who want to buy homes on credit are generally without options when it comes to traditional mortgage lending. Instead,prospective home and apartment buyers have found alternative ways to obtain credit for home purchases. Many of them cut deals with developers.

But developers usually have take-it-or-leave-it conditions, forcing potential borrowers to shop around for better deals. “Only a small amount of developers are offering mortgages, thanks to their strong reputation and pre-arranged agreements with certain banks,” said Perehinets.

The most frequent mechanism is for the developer to obtain financing from a bank and then offer 10-year installment plans with a 50 percent down payment to house buyers.

“Mortgages are more and more being replaced by private credit,” said Mikhail Artyukhov, the director of ARPA Real Estate.

Another mechanism is called a lease with buyout, in which the developer sells apartment leases as the building is being constructed, while the borrower pays the price of the apartment over 5–10 years.

“Currently, it’s only possible to try to support the market, but no single bank has the full capacity to be an active player on the financial market to credit either developers or the population,” said Natalia Tikhovskaya, head of Ukrsotsbank’s factoring and promissory note division.

But since banks refuse to lend except to trusted developers, the developers themselves risk becoming unregulated banks. “Because the developer is not a bank, it’s not its business to engage itself in such long-term relations with buyers,” said Alexander Borodkin, an attorney at Vasil Kisil & Partners law firm.

While the National Bank of Ukraine regulates mortgages and the State Commission for Securities and the Stock Market covers bonds and other financial instruments, these private agreements are, by their nature, self-regulating.

In some cases, fraudsters have used such schemes to promise to build a large apartment complex. The developer will start collecting down payments from excited Kyivans. But instead of using the money to fund the construction, the scam “developer” disappears, leaving people with no apartment and no cash.

Mikhail Artyukhov, director of ARPA real estate, talks in Kyiv on May 17. Artyukhov argues that there is a glut on the Kyiv real estate market.

(Kostyantyn Chernichkin) (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Options still open

Part of the problem stems from the top: developers of new buildings have a hard time finding financing for construction when banks are unwilling to lend.

“It used to be a normal market,” said Borodkin. “But even the performing developers from those times, which are still performing right now, do not have the same options today.”

Only a few banks are still willing to fund construction projects.

The state-owned OschadBank and Ukreximbank finance building by developers KyivMiskBud and UkrBud, which are also state-owned, while private companies either go to trusted banks, draw on their own funds or essentially crowdsource the costs by taking down payments on future apartments as construction begins.

Intergal-Bud, one of the main private developers in Kyiv, offers installment plans that range from six months to building completion to 10 years.

“Developers have the option of partnering with banks on this,” said Anna Laevskaya, the group’s assistant commercial director, adding that the company is working with Globus Bank and soon with Ukrgazbank to guarantee loans for potential buyers at interest rates from 5 to 25 percent.

“Since a lot of the main banks are now negotiating with developers, it’s possible to say that the process is moving forward from a dead point, as the banks have resources again that they can put out,” Laevskaya added.

Mortgage lending collapsed in Ukraine following the 2008 global financial crisis and never recovered. Ukraine’s economic downturn since 2014, exacerbated by Russia’s war, worsened the situation.