In Ukraine, 94 percent of solid waste is disposed of in landfills. But with the available space shrinking, cities are looking for alternative ways to process garbage and use it as an energy source.

Pollution

In May 2016, a massive pile of trash collapsed during a fire at the Hrybovychi landfill near Lviv, killing three firefighters and an ecologist at the site. The local authorities took the long overdue decision to close the dangerously overfilled 33-hectare dumpsite, but the city of Lviv was left without a place to dispose of its waste.

On city streets, dumpsters filled up quickly, and in just a few months Lviv was blighted with suffocating piles of garbage. Residents complained about the bad odors and rats, and demanded action from the city authorities. The city tried to find available landfills in other regions, but there were not many options. Sometimes tons of trash would simply be dumped in unauthorized areas, in fields, drawing the ire of the neighboring towns, which began to block garbage trucks from Lviv.

In Ukraine, landfills already take up 12,000 hectares of land — a territory bigger in area than the city of Vinnytsia. Only a seventh of that is legal for usage and currently open. Even fewer of the landfills meet sanitary standards.

By official figures, less than seven percent of the waste produced in Ukraine is recycled or used to generate energy. Almost 10 million tons of waste ends up in landfills, contaminating soil, water, and the air of the surrounding areas. The only waste incineration plant in the country is located in Kyiv; it burns about 20 percent of all the capital’s waste.

Solutions

To tackle the crisis in Lviv, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development allotted 35 million euros last September to upgrade the Hrybovychi landfill and to build a waste treatment plant.

Shortly after that, the city of Khmelnytsky also announced plans to deal with its waste: In January, the city authorities announced they would build a similar waste treatment plant to Lviv’s.

Waste not

While some private companies and public initiatives try to promote waste sorting and recycling, there’s no such culture in Ukraine, nor is there a functioning nationwide or municipal policy.

“We can’t wait for our people to learn to sort their waste. There is technology that can do it at a plant,” said Serhiy Savchuk, head of the State Agency for Energy Efficiency and Energy Saving.

The technology he referred to is a mechanical-biological treatment (MBT) plant, the type of plants that both Lviv and Khmelnytsky plan to build. It is equipped to separate waste into several types of materials that can be recycled or converted into energy.

Glass, paper, and plastic are recycled. Organic food and agricultural waste is processed into biogas or technical compost, used to cover old landfills. Combustibles can be used to produce fuel. And the remaining small fraction of non-reusable residues can be buried in a landfill.

Ideally, Savchuk says, such a plant should be in every Ukrainian city and region. But in reality, this would be costly and require the revision of legislation and tariffs.

Matthias Vogel, director at the Ukrainian branch of Veolia, a French waste management company, says that Ukraine needs to start from the basics: Get new containers and trucks with GPS trackers; create sanitary landfills; tighten controls over where waste is disposed of; and introduce the sorting of dry and wet waste.

“Unfortunately, the better the recycling, the more it costs,” Vogel said, adding that the basic model of waste management he proposed would cost five times more than the existing one.

Waste-to-energy

Today, Ukraine has 18 biogas plants installed in landfills that generate 16 megawatts of electricity from decomposing organic waste.

But building a more sophisticated power station to convert solid waste into energy requires a lot of investment. For example, French company SUEZ is building a waste-to-energy power station in England for 150 million euros.

“MBT plants are fine for producing alternative fuel, but the big question is where it is going to be incinerated,” Vogel said.

The alternative fuel extracted from combustible waste varies in caloric value and makes up only from 10 to 35 percent of the total volume It can be burnt to produce electricity or thermal power, or used in cement production.

“Some Soviet thermal power stations could be converted to run on alternative fuel or biomass. Theoretically, it is possible. Practically, it’s very costly,” Vogel said.

Low tariffs

It all comes down to money. And at the end of the day it’s Ukrainians who will pay.

With current rates for waste collection and disposal in Ukraine, it is cheaper to dump trash into a landfill than to build processing plants, said Savchuk from the State Agency for Energy Efficiency.

First, tariffs for waste disposal services should be increased, Savchuk said. According to him, the average cost is about Hr 330 per ton now. That includes transportation by a collecting company and disposal in a landfill.

Taking garbage to a sorting plant and further recycling and conversion into alternative fuel and burning that fuel to produce energy would raise tariffs to an estimated Hr 2,000 to Hr 4,500 per ton, according to Vogel’s estimates.

Furthermore, the environmental tax on waste disposal in Ukraine is incredibly low: Hr 5 per ton.

In comparison, in Europe landfill taxes range from 5 euros per ton in Lithuania to over 100 euros per ton in Belgium. The tax is charged in addition to the tipping fee at a landfill in order to increase the cost of landfill disposal and encourage other means of treating waste.

“What we can do now is minimize the amount of waste taken to the landfill. Take out organics and recyclables and do it at the lowest cost. If we don’t start there, we won’t get to another level,” Vogel said.

The next level is to attract investors into the waste-to-energy sector. They need guarantees that their plants will get the necessary amount of waste on a regular basis and advantageous tariffs on sales of the energy they produce.

The state agency is looking for a business model to make waste treatment plants more affordable for Ukraine.

“The construction may be partially covered from municipal budgets or subsidies, or through public-private partnerships,” Savchuk said.

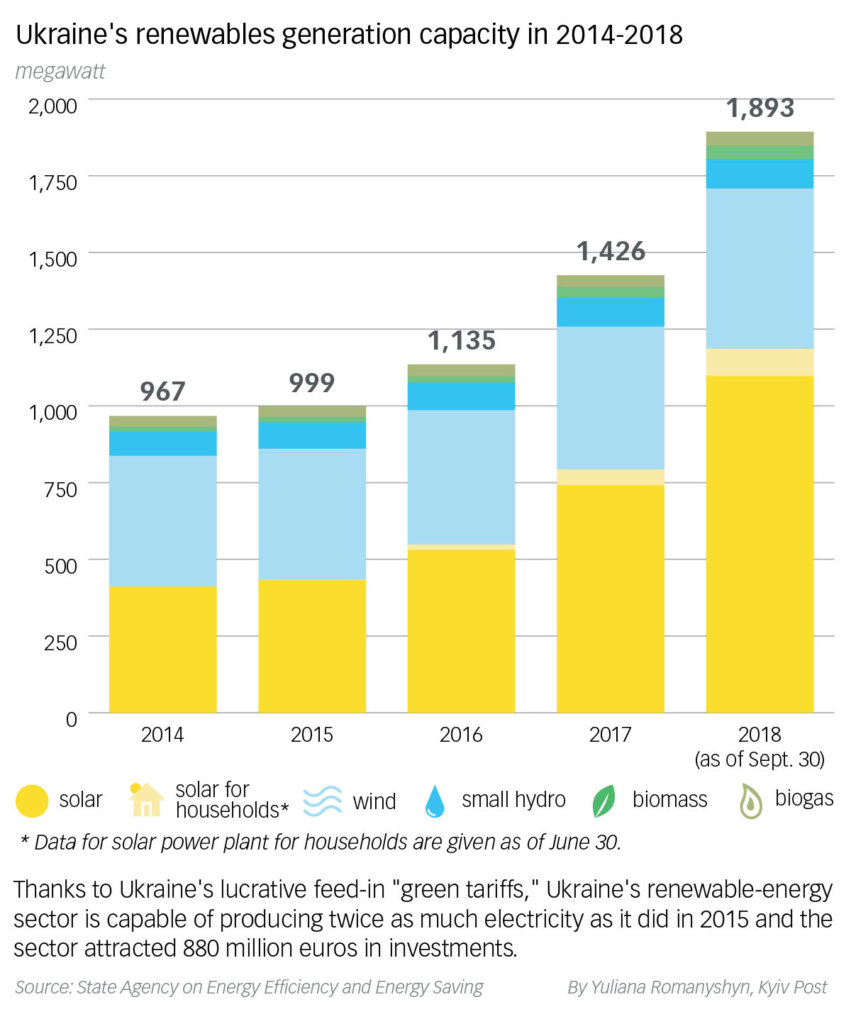

Stimulating tariffs for energy produced from waste, similar to “green tariffs” that Ukraine introduced to boost investment into renewables, would help too, Vogel added

Representatives of French SUEZ met with Savchuk’s team in September.

“Waste-to-energy is among the projects we consider in Ukraine,” SUEZ’s pressperson told the Kyiv Post in an email. “In order to commit to such project we would need the necessary legal framework, access to financing, commitment on volumes and prices of waste, as well as sustainable energy tariffs.”