Taking the train into Poland from Lviv, travellers are greeted by windmills among the rolling hills.

Unfortunately, they’re not on the Ukrainian side — they’re in Poland.

The split is representative of Ukraine’s lagging growth in renewable energy. The country set a goal for itself to have 11 percent of its energy generated from renewable sources by 2020.

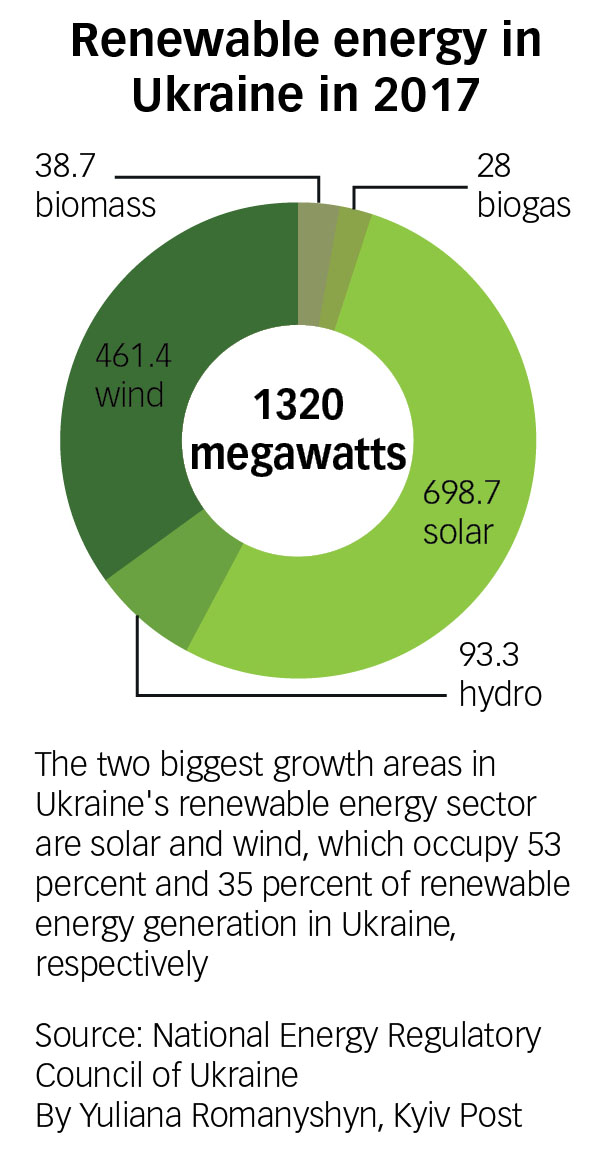

But, at the halfway mark from when the goal was set in 2014, Ukraine is lagging behind on its renewables revolution. Excluding large hydroelectric plants, at most 1.6 percent of the country’s energy consumption comes from renewable sources, meaning resources that are constantly replenished.

The government has made piecemeal attempts at spurring growth in the area — a “green tariff” gives renewable operators higher profits at more stable, euro-linked rates, while households can buy their own solar panels and sell excess energy back to their providers.

But while there has been some substantial investment, mostly in solar — including plans to turn the Chornobyl exclusion zone into a solar farm and a Canadian solar farm in Nikopol — these projects have been slowed down by many of the same issues that plague other areas of Ukraine’s economy.

All of this will be discussed at the Renewable Revolution panel at the Kyiv Post’s annual Tiger Conference, held at the Hilton Kyiv Hotel on Dec. 5.

“The energy field up until now has been dominated by special interests and oligarchs,” said Edward Chow, the Center for Strategic and International Studies Senior Fellow who will moderate the panel. “This has led to a lack of investment.”

Olexiy Orzhel, chairman of the Ukrainian Association of Renewable Energy, who will also speak at the panel, said that while Ukraine “has development, it’s not as complete as in other parts of the world, but it’s showing stable growth.”

Ecology Minister Ostap Semerak will likely face tough questions on his oversight of the State Geological Service, the agency responsible for issuing resource use permits.

Batkivshchyna Party Member of Parliament Alex Ryabchyn, KPMG Ukraine Energy Practice Chief Dmitry Aleev and North University Professor Peter Norre will also speak on the panel.

Green tariff

The keystone of the Ukrainian government’s effort to stimulate renewable energy production is its “green tariff,” a policy administered by the National Energy Regulation Commission or NERC.

The tariff provides incentives for investment in renewable energy, offering higher rates — and therefore, bigger cash flows — for projects in solar, wind, biomass energy, and hydro projects smaller than 10 megawatts.

Hydro plants are limited to a smaller size since the energy and environmental damage required to operate huge hydroelectric plants disqualifies them as renewable. If those plants were included, Ukraine’s overall share of renewable energy production would be closer to 8 percent of the total.

Business owners have complained that the green tariff is awarded based not on merit but rather on factors relating more to vested interests on the market.

The story is compounded by an apparent battle for control over the commission itself.

One commissioner — Borys Tsyganenko — has been absent from meetings since the week of Nov. 13. Since President Petro Poroshenko has failed to appoint additional commissioners to the agency, and an absent Tsyganenko means that the commission cannot make any decisions. Moreover, on Nov. 26, two more members’ terms expired, meaning the board is now completely non-functioning.

“There are three renewable energy projects that cannot get a green tariff right now,” said Andriy Gerus, a former NERC commissioner. “It’s this big problem of setting the wholesale price for next year.”

One of the three energy projects that have been held up is that of Refraction Asset Management, a Canadian company whose Ukrainian subsidiary TIU-Canada has built a solar farm in Nikopol, 427 km southeast of Kyiv.

Unable to get approval from the board, Refraction’s 10 mWh project has stalled without access to the green tariff.

Hani Tabash, the company’s COO, told the Kyiv Post that, “of course we are concerned, but we are confident that the matter will be resolved quickly so that the first investment under the CUFTA can move forward to help Ukraine become energy independent.”

Last year, a state-owned Chinese company took control of solar plants in Odesa and Mykolaiv oblasts that used to belong to the Klyuyev brothers, Andriy and Serhiy, Ukrainian politicians and businessmen who fled the country after the fall of the regime of former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych.

After the ownership transfer, which came in part after the Klyuyevs defaulted on a loan they had gotten from the Chinese, the tariff stopped being awarded to the plants.

“The action — or, more correctly, the inaction — of the NERC is a gross violation of Ukrainian legislation,” Yun Xi Chen, the company’s Ukraine chief, told Interfax.

The NERC did not reply to a request for comment.

Solar from scratch

Roman Babyachok in Lviv oblast who owns a company called SolarLviv faces other problems.

As a small business owner, Babyachok had trouble getting off the ground. In 2013, when he first started operating and selling solar panels, the local oblenergo (regional energy distributor) refused to work with him.

“It only started to work in 2014,” he recalled, “after the change of power.”

Babyachok sells solar panels, an area that could be lucrative for average Ukrainians under legislation that allows them to sell excess energy back to their oblenergo.

“But people don’t have money to spend on this,” he said. “And there’s no real program from the banks or from government to encourage it.”

Different priorities

A simple way of looking at what types of energy Ukraine values is to follow the money.

The country’s total investment in renewables adds up to maximum 500 million euros.

But take DTEK — the Rinat Akhmetov-owned energy company which produces 49 percent of the country’s coal and generates 70 percent of its power.

That company — the largest privately owned corporation in Ukraine — has made Eurobond issuances that exceed the total renewable investment in Ukraine.

DTEK’s 2013 dollar-denominated Eurobonds, for instance, were trading at $36 in March 2015.

But after years of the NERC-approved Rotterdam+ formula, which links Ukrainian coal costs to the prices of coal being delivered to Rotterdam, Antwerp, and Amsterdam, plus freight costs, DTEK has been doing well.

Akhmetov’s debt is now trading at $105.