Foreigners and corruption-fighting Ukrainian politicians have scrutinized the nation’s oil and gas sector more than any other since the 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution that forced fugitive President Viktor Yanukovych from power.

It has a big history as a money tree for corrupt politicians, with energy players getting rich at the expense of Ukraine’s people and state budget.

Over the past six months, despite tough talk from President Petro Poroshenko’s administration, prospects for a more productive and politically independent Ukrainian energy sector have worsened.

The knot of interests that collide over the country’s oil and gas sector has left the country’s biggest oil producer endlessly bleeding money and the country’s gas producer hobbled by corruption schemes.

Meanwhile, Naftogaz – the country’s main state-owned oil and gas firm – is fighting to keep its own progress from rolling back, while critics remain skeptical that it will let go of its monopoly on the country’s gas system.

Naftogaz

Foreign lenders have focused much of their energy on remaking Naftogaz, Ukraine’s state-owned oil and gas company.

Bled dry by graft and rotted by mismanagement, Naftogaz has long been a hulking monopoly that sucks money out of the state budget — up to 7 percent of the nation’s gross domestic product as recently as three years ago. Now it is close to break-even.

Since the 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has agreed to loan Naftogaz money to buy natural gas from Western Europe, giving Ukraine $300 million in a revolving loan to survive each winter.

But the main focus has been on making the company profitable via management reforms.

Eventually, Naftogaz would have its monopoly on Ukraine’s oil and gas market broken and become one of many competing firms, with its gas storage and transmission divisions spun off into separate companies.

Foreign creditors scored a significant victory in July when parliament passed a bill that set in motion a process by which the country’s gas pipelines and gas storage centers will be spun off into separate firms, according to parliament member Nataliya Katser-Buchkowska from the People’s Front.

The fuel and energy committee member said that Naftogaz is not a “black hole anymore” in the Ukrainian budget, thanks also to increased tariffs on home gas usage.

But others argue that Naftogaz’s management is not really committed to breaking up the company’s monopoly on Ukrainian oil and gas, but is rather only interested in making it a more efficient business.

“They are good CEOs and doing everything they can to develop the company, but they are not statesmen,” said Oleksiy Ryabchyn, a member of parliament with the small Batkivshchyna Party faction.

He is on the energy committee.

One main task is to turn Naftogaz’s gas pipeline transportation system into a different company.

“It would be more understandable and clear if these functions were separated, not only by law, but in real life,” said Roman Opimakh, executive director of the Gas Producers Association of Ukraine.

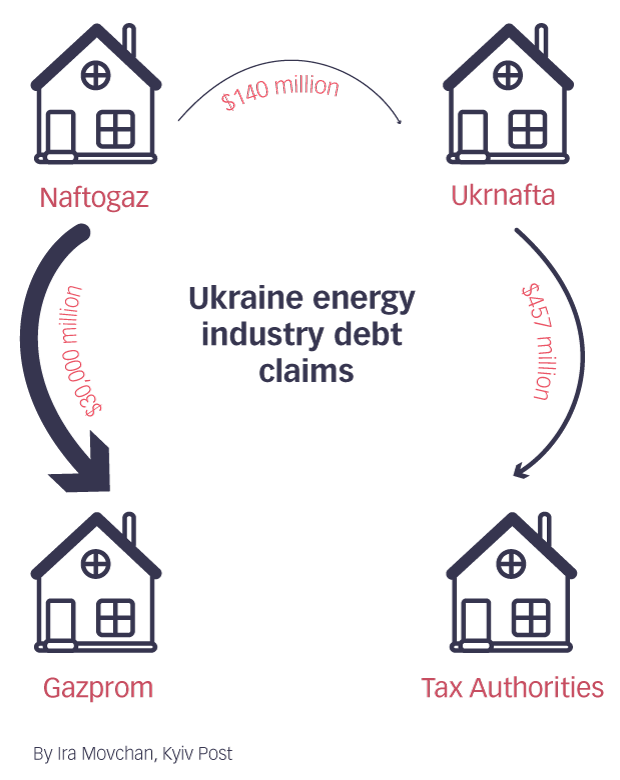

But the process has been halted due to a $28.3 billion arbitration lawsuit filed by Gazprom against Naftogaz in Stockholm, Sweden. Until the litigation is settled, the company will be unable to break itself apart.

Ryabchyn suggested that this plays to the company’s advantage.

“They have a major desire not to lose their monopoly status,” Ryabchyn said.

Ukraine’s energy industry is caught in a web of debt

Ukrnafta

Ukrnafta, the country’s oil producer, has been stagnating over the past six months as it struggles under the weight of a Hr 12 billion ($458 million) debt to the country’s tax authorities. The debt increases as State Fiscal Services chief Roman Nasirov fines the firm for not paying up.

The company is majority owned by Naftogaz, but has been de facto controlled by its minority shareholder, Ihor Kolomoisky.

Kolomoisky filed an arbitration suit in Stockholm claiming an additional $4.6 billion in debt against the company, which produces 68 percent of Ukraine’s oil.

An oil pumping tax rate of 45 percent is slowly bleeding the company dry, leaving it unable to invest in any new drilling or modernization.

New management arrived at the company last year with a debt restructuring plan that would allow the company to climb its way out of the tax service debt and invest money in modernization. But two shareholder meetings to approve the plan have not managed to go forward, leaving the company bleeding money without a way to recover.

“No progress,” said Gennadiy Radchenko, an executive vice president at Ukrnafta.

The lack of agreement on how to solve the company’s debt problem appears to be a symptom of a larger battle between Kolomoisky and the government, with Ukrnafta as an expensive pawn.

“If the current situation continues, Ukrnafta will go bankrupt,” said Gennadiy Kobal, an analyst at Expro.

Kobal added that even the most profitable parts of the company – its oil wells – would lose most of their value after a bankruptcy – since it would be too expensive to restore them to working order or connect them to a new system.

The company anticipates a 15 percent drop in production this year.

Ukrgazvydobuvannya

Ukrgazvydobuvannya, the country’s state-owned gas extractor, has set forth an ambitious plan to make Ukraine natural gas independent by 2020.

“We need to drill more wells,” said Opimakh, the gas producer association executive director.

Opimakh has proposed that the tax rate on gas extraction on future exploration be lowered to 12 percent. He argues that this would allow foreign investors to partner with UGV on production sharing agreements for the country’s eastern gas fields.

The company lacks the massive debt of Ukrnafta. It can afford to spend money on modernizing equipment and drilling new wells.

The initiative is government-backed. According to Katser-Buchkowska, the production-sharing agreements could cause problems for UGV.

“There are difficulties with some” of these agreements, she said, pointing out that UGV lost 380 million cubic meters of gas under similar sharing arrangements.

The company continues to be susceptible to corruption. Former member of parliament Oleksandr Onyschenko is accused by the General Prosecutor’s Office to have embezzled Hr 1.6 billion ($61.5 million) from the company from between January 2014 and July of this year. Onyschenko fled Ukraine in July, and denies the charges.

Extensive bureaucracy may also sink plans to use the company to make Ukraine gas independent. It currently takes years to secure a license to drill a new gas well.

“It’s insane,” said Opimakh.