When DTEK is doing well, Maxim Timchenko says he doesn’t speak often with its owner, Ukraine’s richest billionaire oligarch, Rinat Akhmetov. When a crisis hits, they talk more often.

And now?

“We’re in crisis,” Timchenko told the Kyiv Post. And that means frequent talks with the owner, who put Timchenko in charge of DTEK, Ukraine’s largest private energy company, 15 years ago.

DTEK finds itself with troubles on two fronts: Assaults on its reputation, partly because of public antipathy to its reclusive yet powerful owner, and falling financial performance in Ukraine’s precarious energy market, one that is often marred by debts, bad regulation, and dysfunction.

The COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s six-year control over parts of Akhmetov’s former Donbas economic stronghold, with no end in sight to either malady, haven’t helped either.

“No one can predict what will happen in Ukraine,” Timchenko said on May 5, from his 27th-floor office in the DTEK Tower in Kyiv.

Life has eased up a bit in the three weeks since his expansive 90-minute interview with the Kyiv Post, in which he dazzled with an impressive flow of spreadsheets, complicated pricing schemes, and grasp of arcane facts that show his mastery of the energy sector.

DTEK, for instance, restarted on May 16 its best coal mining complex, some 560 kilometers southeast of Kyiv in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast’s Pavlohrad, a city of 118,000 people. The company closed the mines on April 20 because of falling prices and tumbling demand for electricity. Energy use is again on the rise after Ukraine began easing its COVID-19 lockdown this month.

Also, as a major investor in renewable energy power, with a 15% market share as of the 1st quarter of 2020, DTEK and others in the sector are making headway against deep reductions in the guaranteed price – or “feed-in tariff” — that the state pays to renewable energy providers.

After first setting high prices to attract investors, Ukraine’s government is now saying it can’t afford such generosity. The debt of Ukraine’s state Guaranteed Buyer is approaching $500 million.

A proposed voluntary cut of 15% for the solar industry and 7.5% for wind power has been proposed to President Volodymyr Zelensky. But the president has reportedly not yet approved it.

Top-to-bottom crisis

The coronavirus shutdown that began on March 12 in Ukraine accelerated existing challenges for Akhmetov and DTEK.

While the poorest and the jobless have suffered the worst, Akhmetov’s fortune is also sliding, according to Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index. Its daily update as of May 27 estimates that Akhmetov is the 420th richest person in the world, with wealth at $4.7 billion – more than $1.3 billion less than at the start of 2020.

As for DTEK, it is subdivided into six holding companies and part of Akhmetov’s System Capital Management conglomerate. With nearly $6 billion in revenue in 2018 and 71,000 employees in DTEK group, one of its six companies, DTEK Energy, is now busy trying to restructure $1.9 billion in debts after stopping payments to investors on Eurobond coupons in April.

The problems, Timchenko said, are a symptom of Ukraine’s dysfunctional energy markets in which some of the main government positions are held by inexperienced leaders and in which regulators, he said, have mandated tariffs below the cost of production while keeping a complicated array of subsidies that retard the market.

The circumstances have created a cascade of unpaid debts among producers and consumers while keeping the sector starved of the billions of dollars in yearly investments needed for infrastructure development and exploration.

Fighting ‘manipulations, myths’

But Timchenko says that while many energy experts and insiders agree with his analysis of solutions, he is frustrated in getting his story told to the public.

Akhmetov is one reason why. Their relationship goes back to 2002 and both claim Donetsk, the southeastern industrial city of nearly 1 million people now under Russian occupation, as their hometown.

While Akhmetov installed Timchenko 15 years ago to establish Western standards of professionalism, openness, and transparency in his companies, the owner remains secretive. He rarely if ever gives interviews. Public sightings of him are practically non-existent. He is faulted for being incurably tone-deaf, or simply indifferent, to how his actions go over in a poor country.

“Unfortunately, the reputation of this company is not so much dependent on its practices or its internal life. It’s very open, formulated by other stakeholders,” Timchenko said. “And unfortunately, I spend a lot of my personal time fighting these manipulations, these myths about our behavior.”

Akhmetov’s house

One purchase of DTEK’s owner this year that didn’t go down well publicly was the news in January that Akhmetov spent $218 million to buy a luxury estate in the French Riviera. It was once owned by King Leopold II of Belgium, who built a fortune by enslaving Congo in the 19th and early 20th centuries, killing an estimated 10 million people.

Such stories only revive memories of how Akhmetov emerged from Ukraine’s wild 1990s on top. That was an era of crony capitalism, rent-seeking, rigged privatizations, and assassinations.

One of his business partners, Akhat Bragin, was killed in a bomb attack on Oct. 15, 1995, in Donetsk’s Shakhtar Stadium. Akhmetov became president and chairman of the football club after the murder, which remains unsolved after Ukraine’s Supreme Court overturned the conviction of former Donetsk police officer Vyacheslav Synenko in 2008. Other prominent Donetsk businessmen murdered during this era included Yevhen Shcherban, then a member of parliament, and Alexander Momot, both in 1996.

The French property is not the first acquisition that garnered international headlines for Akhmetov. His 2011 purchase of One Hyde Park for $210 million, then a record price for London real estate, made quite a splash as well.

But that is history.

What is relevant, Timchenko said, is that Akhmetov’s real estate division is in business to buy and sell properties.

“What is bad is that there isn’t a proper explanation of this deal. It’s purely an investment, it’s not property to live in. It’s one of the strategies for diversification, it’s not a scam. They develop a real estate portfolio,” Timchenko said. “My question is why don’t you guys explain it properly to the market? Because again, this is speculation that’s used against us.”

Aside from the recurring PR hits, Akhmetov and DTEK are far from powerless.

When Ukraine’s government decided to rebalance Ukraine’s electricity sector away from nuclear power in favor of coal-fired and renewable options, which favor the strengths of Akhmetov’s DTEK, many saw it as another sign of the oligarch’s political clout – now enhanced by a prime minister, Denys Shmyhal, who was a DTEK executive. Besides Shmyhal, acting energy minister Olga Buslavets has made moves in the company’s favor.

Timchenko said the idea that a DTEK lobby is now running the government is false. He said that Shmyhal and Buslavets are simply competent authorities who understand the energy sector and, therefore, can act in the nation’s best interests, not carry the company’s water.

DTEK’s wind turbines operate at sunset in Zaporizhia Oblast on Nov.15, 2019. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

A sector in crisis

While he finds himself defending a boss to whom he is deeply loyal, his main job is to run Ukraine’s largest private energy holding and a top electricity producer. DTEK’s assets are dominant in private coal and thermal power generation, while also being extensive in oil and natural gas production, electricity distribution and in renewable energy.

And wherever one looks, he said, the energy sector is in trouble.

“It’s not the crisis of DTEK,” said Timchenko. “If you ask nuclear, renewables, coal – everybody says ‘guys, we’re in a very, very bad situation right now.’”

Timchenko is right. Ukrainian energy currently faces weak demand and high debts to and among energy producers. The producers, their industrial consumers, and government officials all say that something should be done. However, they don’t all agree on what.

Timchenko has joined talks with the Anti-Crisis Energy Headquarters, a group of industry and government leaders, led by Shmyhal, to bring the sector out of crisis.

Besides the shift that favored renewables and coal-produced electricity, DTEK has also supported easing price caps, a renewed ban on electricity imports from Russia and Belarus and other favorable shifts in government policy this year.

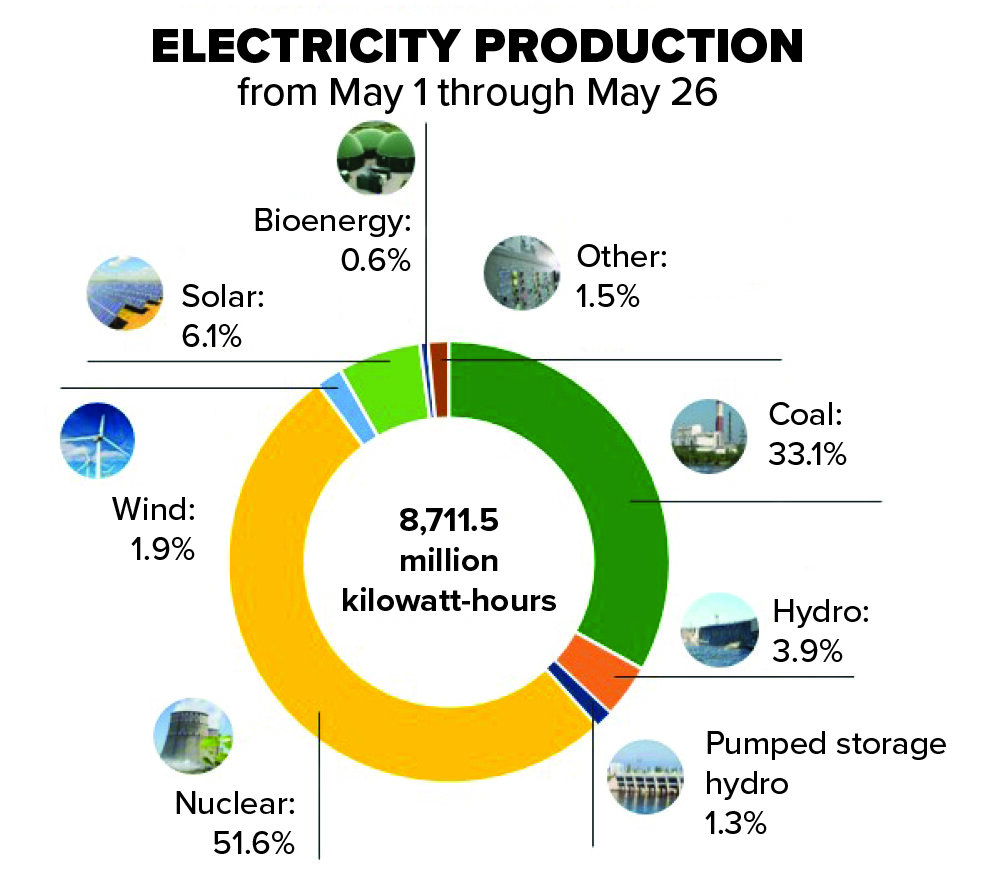

The energy ministry has cut nuclear output to new lows. Hydroelectric power is down as well, due to low river water levels caused by an unusually mild winter. Only green energy has not been cut. Coal sees some reduction but remains prominent in electrical generation.

The change, Timchenko said, is sensible and represents “a balanced approach” even if the public and some energy officials don’t understand all of the intricacies and may draw wrong conclusions.

“This is something that stays challenging for us how to explain in simple terms,” he said.

Nuclear power

Critics such as parliamentary energy committee head Andriy Gerus and others warn that the shift away from cheaper nuclear power will cause energy prices to rise for industrial consumers.

Timchenko said, however, that use of nuclear power had reached dangerously high levels amid falling demand.

“The share of nuclear energy is staying the same. Because of low consumption, you know that nuclear is very slow to decrease because of general level consumption and if you look at statistics for the last half-year, the share of nuclear was around 55-60 percent,” he said. “And the situation became so dangerous that, in some hours, the share of nuclear power was as much as 75%.”

“There were hours when they had to lower load by 30%,” Timchenko said. “So they’ve come to this situation where it’s dangerous because there’s no mass consumption and there is not enough hydro(-electric power) because of warm weather and not enough snow and hydro cannot produce a lot of electricity.”

Into the mix comes DTEK. “We provide flexibility,” he said, with coal-fired electricity.

Besides, he said, nuclear power is not so cheap after its hidden costs are taken into account.

The government’s Energoatom sets aside $30 million a year for decommissioning nuclear power units or $2 million annually for each of Ukraine’s 15 reactors. The price of decommissioning, which must start in 10 years with the aging fleet, is $500 million to $800 million per unit.

“It means that this part of the nuclear tariff is not part of the cost of production,” he said. Moreover, the government is not factoring in the ongoing costs of Chornobyl and other experts cite the long-term storage costs of nuclear waste.

“This is another manipulation, saying that we have very cheap nuclear power.”

Nonetheless, the sector is also in crisis, with Shmyhal noting that Energoatom is also forced to sell below production costs, prompting the Cabinet of Ministers to reduce the sector’s mandatory sales to the state’s Guaranteed Buyer.

DTEK CEO Maxim Timchenko speaks with the Kyiv Post in his office in Kyiv on May 5, 2020. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Future is in renewables

While Timchenko thinks polluting coal-fired plants will be needed for at least a decade in generating electricity, he said Ukraine’s future is in expanding the share of renewable energy.

“When we announced that we want to be a leader in decarbonization, it sounds strange when a coal company makes such a statement. But what’s more important is that it’s true,” he said. “The main power should be renewables. It’s without any doubt. Ukraine should go in this direction. It’s good what was done for the last few years. We have more than $10 billion in investments. It’s the first time we’ve had such big investments in generation capacity on an industrial scale. This is a good experience for investors on the market. Most investors in renewables are foreign investors. It’s in line with the trends and the path of the Europeans.”

DTEK, Timchenko noted, started investing in renewables in 2008, long before the government’s generous price guarantees, and has staked out “a consistent position” to build the sector. “We fulfilled our goal of building 1 gigawatt capacity,” he said, and are looking to add another 1 gigawatt.

“Again, now people are saying that DTEK is protecting renewables because we are a leader. Yes, we have 15% but not 75%, not 80%, of the renewable sector,” he said. “You should have long-term vision. If we make a stupid mistake and scare renewable investors today for the sake of 1 billion hryvnia ($370 million) or 2 billion hryvnia ($740 million) they get in reduction of tariff over the next 10 years, then they will kill the future of this sector.”

He acknowledges that the government promised higher prices for such energy than it can pay. While renewables produce 8% of Ukraine’s power, experts estimate its share now costs up to 25% of the money spent on energy.

“I fully accept that continuing building new farms with the current feed-in-tariff is unsustainable. We have to change the situation,” he said. “We publicly said this in May 2019, when new laws were discussed and approved to move to auctions. If we bring new auctions, we will lower tariffs.”

He said more than 50% of the cost of renewables is tied up in high financing costs for construction, not actual production of energy.

“What we see as a trend as a result of investment in renewables is a decrease in the cost of electricity production in European countries,” Timchenko said. “You make a huge investment at the beginning and then you pay not much for air and sun. I think that Ukraine should reach a situation like Germany today — 50-60% renewables. But first, we need a sustainable form of tariffs. And second, our system should be prepared to carry such a high volume of renewables and it means a lot of investment in transmission lines.”

For nearly a year, Ukraine’s political leaders have wrestled with the state’s guaranteed price. Cutting it too much risks scaring away investment in all sectors, not just renewable energy. Timchenko said proposed cuts of 20% or more are unacceptably high.

While Timchenko holds up Germany as a role model, about 43% of its energy production still comes from coal and gas plants, and coal generation in Germany will only phase out by 2038.

“You’re right in saying that today, flexible power capacity to support such a volume of renewables needs coal,” he said. “How do we replace it? First, hydro… Second, we should bring incentives for investors to start investing in energy storage.” DTEK is investing in a pilot electricity storage center, which Timchenko hopes to scale up.

“I am convinced that this solution can be found without a sharp increase of tariffs for consumers and I hope that this package will be developed and presented to the public in May,” he said.

Ukraine’s energy balance as of May 26. (The Ministry of Energy and Environmental Protection of Ukraine)

Coal’s future

Critics accused DTEK Energy of shutting down mines despite being profitable. Pavlograd Coal, DTEK Energy’s most significant coal asset, made a net income of Hr 6.7 billion ($250 million) in 2019, according to documents published in the media.

Timchenko responded that Pavlohrad Coal is profitable “on paper” and that the income was largely a result of the re-evaluation of the company’s debt portfolio. He added that with the Hr 7 billion ($260 million) unpaid debt of the former government enterprise Energorynok and a coal stock of 2.5 million tons, the company “has no profit in cash terms.”

Even amid the shutdown, he said, DTEK Energy continued to pay salaries to laid off miners, although at a 40% reduction, before re-starting the mine. But the situation remains fragile. “Yes, probably they will have demand for coal. But I have to pay salaries, I have to pay taxes, transportation, and I cannot pay when I have tariffs…below the cost of production.”

DTEK’s debts

Timchenko said DTEK Energy is trying to restructure $1.9 billion in debt, a process on May 5 that he estimated would take two or three months. The last time that the group needed debt restructuring was in 2014, the start of Russia’s war against Ukraine in the eastern Donbas.

“Unfortunately, we are in a position, mostly artificially created by decisions of the regulator and other decisions on the market where we cannot service our debt,” said Timchenko.

He is confident he and the company’s investors can reach an agreement.

“Everybody’s seen how we behaved in the difficult years after 2013, not like some other Ukrainian companies who did restructuring for 10 years and eventually did a ‘haircut’ of 40-50%,” meaning a reduction in investors’ assets. “In our story, we never did a ‘haircut,’ we always tried to be open in our position with investors and find a solution.”

Dysfunctional market

Timchenko echoed the words of the director of the European Energy Secretariat, Janez Kopac, in saying that Ukraine’s subsidy-rich energy sector is distorting the market. While price caps made sense for an oligopoly market like in Ukraine, Kopac said, they need to be phased out.

Oleksandr Kharchenko, director of Energy Industry Research Center, said that politicians aren’t willing to take the unpopular step of increasing the population’s energy costs. This is one major reason, he said, why Ukraine is stuck without a fully-developed, competitive market for energy.

Russian imports

Timchenko considers a ban on Russian and Belarusian electricity imports to be a matter of national security. Gerus controversially introduced them last year, but the government has since rescinded them. To allow Russia to export electricity to Ukraine for prices lower than they sell it in Russia is “strange in a situation where there’s overcapacity in Ukraine,” DTEK’s CEO said.

While DTEK favored a “competitive open market” that opened the possibility of imports of electricity as of July 1, 2019, trade “should be a two-way flow,” Timchenko said. “We never criticize imports from Slovakia, from Western countries. But it’s a different situation with Russia and Belarus because these guys are exporting electricity to our country and we ask why aren’t you allowing the import of Ukrainian electricity?”

An unavoidable exception, he said, is the import of anthracite coal from Russia because this type of fuel is found only in Russian-controlled territory areas of the Donbas. But eventually, he said, those imports would cease also.

“The best way is to have our own resources. It’s about national security, it’s about government policy, it’s about the position of local producers, it’s about taxes we pay,” he said. “This is a good indication of whether we are proponents of market reforms and import of electricity or not. And we are in support of them.”

Read previous Kyiv Post interviews with Maxim Timchenko:

Maxim Timchenko: Energy sector needs $90 billion in investment – Nov. 21, 2019

DTEK’s CEO rebuts critics of latest privatizations – Feb. 2, 2012

View From The Top – Sept. 23, 2011