Thousands of outraged Ukrainian farmers from across Ukraine descended on Kyiv in late May in an attempt to block new import quotas on fertilizers. The limits, they said, would help monopolies and drive up an essential cost of food production.

Standing in front of the Cabinet of Ministers, they protested against a proposal by the Economy Ministry to cut fertilizer imports to 30%, a move that was supposed to make room for domestic producers.

But farmers, agrarian associations, industry experts and economists say such a decision might allow exiled oligarch Dmytro Firtash monopolize the market. He owns agrochemical giant Ostchem Group and controls 80% of domestic mineral fertilizer production. Firtash is currently fighting extradition from Austria to the U.S. on bribery charges that he denies.

Experts also say billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky would also benefit from the ban, albeit to a lesser extent.

“It would kill the competition on the market,” said Sergiy Ruban, head of the Union of Producers, Importers and Traders of Agrochemistry and Agro Technologies. “The freedom of choice would be removed.”

Although the government overturned the decision to impose import quotas for fertilizers on June 24 due to pressure from agricultural producers and associations, experts worry that future attempts to monopolize the market could still succeed.

Representatives of the largest Ukrainian chemical plants, the Ukrainian Chemists Union, are already preparing to appeal to the government to impose the quotas again.

In their statement, they called the current quotas “anti-state” and said they are destroying the domestic fertilizer industry.

Deadly quotas

Experts predict that a monopolized fertilizer market would severely harm the agricultural industry, which accounts for nearly 15% of gross domestic product and 44% of the country’s exports, a total of $22.4 billion in 2019.

They forecast significant decreases in farmers’ profits, even bankruptcy for many of them, and much less income tax revenue for the state budget. Fertilizer prices might jump by as much as 30%. So might the prices of basic food staples — flour, pasta, baked goods, vegetable oils.

In the long run, agricultural output from Ukraine’s soil could decrease if farmers can’t use enough mineral fertilizer, which looks like large salt crystals and helps keep harvests high even when the soil has been overused through repeated planting.

“The profitability of our company will decrease sharply when the cost of production increases,” Grigoriy Tulba, a farmer from Odesa Oblast, said during the protest in May. “This is the destruction of our agricultural business.”

Even now, Ukrainian farmers use less fertilizer than their European counterparts. Despite the growing demand for fertilizers, Ukrainian farmers use only around 123 kilograms per hectare, while Germans use 202 kilograms and the Dutch apply 258 kilograms, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Oleg Nivievskyi, an assistant professor at the Kyiv School of Economics, said that the proposed quotas would just “do more harm than good for the sector” and that foreign rivals actually help the domestic fertilizer industry to develop “new thoughts, new technologies, and new approaches.”

Overall, the quotas could cause a loss of nearly $240 million, while also costing farmers an additional $500 million, according to Nivievskyi.

Moreover, responding to Ukraine’s actions, the European Union could set up its own set of restrictions — not just on fertilizers, but also on other agricultural products, Nivievskyi said.

“It will be a double blow for agricultural products, which Ukraine mainly exports (to the EU),” said Nivievskyi.

According to Maria Chaplia, a European affairs associate at the Consumer Choice Center consultancy, the EU’s largest fertilizer companies asked Ukraine to abandon the plans to change the quota policy.

Attempts to change the quotas were “an indisputable sign that strong lobbying interests are interfering in the formation of the country’s trade policy,” said Chaplia.

Former Economy Minister Tymofiy Mylovanov said it’s bad policy to support one subsector if it damages the entire agriculture industry, or even the entire economy.

“There are many decisions like that in Ukraine,” said Mylovanov. “And it partly explains why Ukraine is a poor country.”

At the same time, Taras Kachka, deputy economy minister, said that Ukraine is seeking to balance the interests of importers and the domestic fertilizer industry.

“There is a battle over Ukraine as a market for selling fertilizers,” said Kachka on June 11 at an online meeting organized by the Kyiv School of Economics.

The main task of the ministry, he said, is to keep prices reasonable while maintaining the share of domestic production. Kachka also agreed that imposing quotas without regulating prices would lead to “more risks than advantages.”

Dmytro Firtash has sat at the top of the fertilizer heap for a long time. His control over the gas market allowed him to dominate the industry in which the top product has natural gas as a primary ingredient. Nevertheless, he has allegedly tried to use state attacks on his competitors to increase his control. (Kyiv Post)

Key player, own rules

Ukraine has six major fertilizer plants. Firtash controls four of them. Kolomoisky owns another one. The last, the Odesa Portside Plant, belongs to the state.

Firtash started acquiring fertilizer plants in 2010 under the administration of ousted former President Viktor Yanukovych.

As he was building his fertilizer empire, Firtash received around $12 billion in loans from Russian banks. The oligarch set up a company in Cyprus called Ostchem Investments, a move that allegedly allowed him to avoid paying taxes in Ukraine, the Reuters news agency reported.

By the end of 2011, Firtash owned four plants: Severodonetsk Azot, Cherkasy Azot, Rivne Azot and Concern Stirol.

As a result, the businessman became the fifth largest producer of fertilizers in Europe.

“90 percent of (fertilizer) production potential… in Ukraine is controlled by one oligarch,” said Ruban, the union leader.

After Russia started the war in the Donbas in 2014, Stirol — one of the oldest chemical enterprises in Ukraine — wound up in the Kremlin-occupied part of Donetsk Oblast and Ukraine started to gradually ban trade with Russia.

That only gave Firtash bigger profits. With the reduced imports of fertilizer from Russia, the price for Firtash’s products inside Ukraine jumped by 50–100%, as his factories became the main suppliers to the market, according to Andriy Dykun, head the All-Ukrainian Agrarian Council.

This proves cheaper imports are essential to Ukrainian farmers’ incomes.

According to Sergiy Ivashchuk, a farmer from Khmelnytsky Oblast, he saves around $40,000 annually on wheat alone because he imports fertilizers and they are cheaper than the local ones.

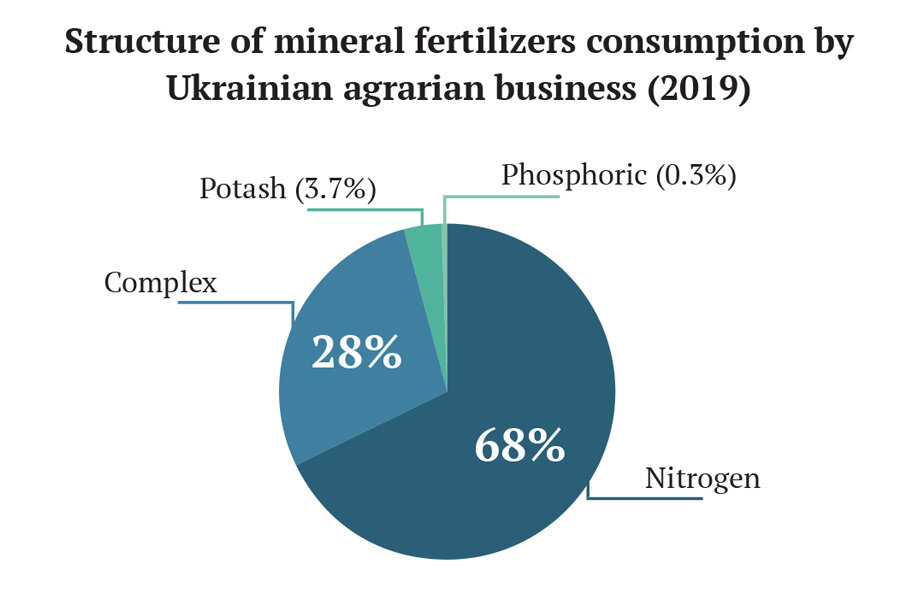

Ukrainian farmers used around 2 million tons of complex fertilizers in 2019 and nearly 4 million tons of nitrogen fertilizers. Combined, both types of fertilizers make up more than 95% of the total fertilizer market in Ukraine. (Source: Analytical group Pro-Consulting)

More expensive for locals

For the past two years, the nitrogen fertilizer market in Ukraine grew from 3 to 4 million tons and, in money equivalent, reached $1 billion, according to Sergiy Povazhniuk, vice director at the Ukrainian Industry Expertise think tank.

Imports grew with it — from 20% to 40%. Over the first 10 months of 2019, imports of all fertilizers reached 3.4 million tons, or $1.1 billion. In the next two years, Povazhniuk predicts that the amount of nitrogen fertilizers will reach 4.5 million tons, or $1.3 billion.

Meanwhile, the prices for nitrogen fertilizers are 30% higher in Ukraine than elsewhere. “At the moment, Ostchem earns very high profits in Ukraine, something that it cannot do on foreign markets,” said Dykun.

He says the quotas would only strengthen the oligarch’s monopoly, giving Firtash more money “to solve the problem of his old and not modernized plants,” which require more natural gas, the main component in the production of fertilizers, than plants abroad. Firtash’s spending will be “at the expense of Ukrainian farmers,” Dykun said.

But Igor Golchenko, vice president of the Union of Chemists of Ukraine and a director for government relations at Firtash’s Ostchem, said the quotas might give predictability and stability to the Ukrainian chemical industry, improve production and provide money to modernize the plants.

“Those who oppose these restrictions are working against the industry, trying to bring back the speculative market,” said Golchenko. “The sale of imported fertilizers in Ukraine is in the interest of many influential business structures, and not only Ukrainian ones.”

However, expert Ruban says protectionism would lead to shortages on the market, squeezing smaller farmers the most.

“The creation of a super monopolist will mean not only the growth of prices, but also it will mean quantity dictatorship,” said Ruban. “When alternative suppliers disappear, the main player on the market will dictate his own rules.”