The government has paid out more than Hr 80 billion ($3 billion) to Ukrainian customers with insured deposits in the nation’s 80 collapsed banks since 2014.

But little of that money, and as well another $5 billion in losses from uninsured deposits, has come from bank owners, managers and shareholders, who pocketed billions of dollars of Ukrainian deposits through insider loans and other embezzlement schemes.

The Deposit Guarantee Fund has filed more than 3,000 criminal reports to law enforcement agencies- 376 of them linked to owners and top managers of insolvent banks. However, this approach has yielded poor results. To date, there have been merely two convictions of bank owners or top management.

In comparison to the thousands of criminal reports, the fund has filed a total of seven civil lawsuits throughout 2014 and 2015 against the bank owners and shareholders of Tavryka, ERDE, Forum, and Mercury banks, amounting to claims of Hr 13.4 billion ($510 million).

A woman with Delta Bank cards hanging on her neck attends a rally of depositors of collapsed banks in front of parliament on Nov. 15. (Volodymyr Petrov)

Despite losing all seven lawsuits, the fund has come under fire for failing to further pursue the civil route against bank leadership, which has proven effective in many other countries, including Russia.

Andriy Olenchyk, the Deposit Guarantee Fund deputy managing director, admitted that the organization struggled in its pursuit of civil claims.

Both banking sector experts and anti-corruption authorities have criticized the organisation for repeatedly forwarding criminal cases to the Prosecutor General’s office, where the investigations typically stall.

Even in the cases of Mikhailovsky and Delta banks, where top officials called for the arrest of the their owners, neither Viktor Polishchuk nor Mykola Lagun have been arrested to this day.

According DLA Piper partner Oleksandr Kurdydyk, on average civil claims took 30 to 40 percent less time to reach a resolution compared to criminal.

Furthermore, Igor Budnik, head of the risk management department of the National Bank of Ukraine, at Kyiv Post’s 5th Tiger Conference on Nov. 29, said the evidence bar for civil lawsuits is lower — requiring only to prove guilt in civil cases by a preponderance of evidence rather than beyond a reasonable doubt, the criminal standard.

Olenchyk said the fund was currently renewing its efforts to pursue civil lawsuits with the help of international agencies, but legislative amendments in this area were also key if the fund was to have any chance of success.

He said in one case against Forum Bank, co-owned by former Party of Regions members of parliament Vadim Novinsky, the court decided that the real sum of the losses could not be determined until all the assets were sold.

“(We would have to) finish the liquidation, and then after a few years we’d be able to understand the difference between creditor’s demands and assets…this is all without long-term prospects.”

“Other lawsuits were based on lack of evidence and often the emphasis was on the fact that guilt wasn’t proven.”

Olenchyk said by the time a bank is declared insolvent and the fund steps in as a temporary administrator, the evidence is typically gone.

Following pressure from the International Monetary Fund, changes to legislation in 2015 gave the fund more freedom to file civil lawsuits.

However, Olenchyk said that the amendments were minor and did not address key problems, such as alleviating the fund’s responsibility to prove the bank shareholders’ guilt.

Furthermore, from September 2015, new fees were introduced that would see the fund charged up to 1.5 percent of the claimed amount for every civil lawsuit it filed.

A fund spokesperson told the Kyiv Post the money for the court charges would be taken from the liquidated bank assets, which is used to satisfy claims of creditors of the banks.

Olenchyk said the fund tried to address the issue with the Ministry of Finance but it fell on deaf ears.

He said the fund was however open to assistance and advice on filing civil lawsuits.

Furthermore, he said the fund was going to be working with international companies to assist them with insolvent bank projects.

Daria Kaleniuk, executive director at the Anti-Corruption Action Centre, said civil claims were the only feasible solution for Ukraine considering there is no will to pursue criminal cases.

“I think civil cases, especially targeting beneficial owners internationally and their assets internationally, this is the way moving forward. Even if we hire private firms and they can work for a possible percentage of recovery… if we identify 100 percent but recover 40 or 60, it’s already more than zero,” she said.

She said it was also important to address the issues in the law, which were hindering the Deposit Guarantee Fund from pursuing further civil claims.

“There should be no fees in the percentage of the possible claim …for the Deposit Guarantee Fund to start the civil claim,” she said.

“The law also says that first you have to calculate the amount of debt and amount of remaining assets to be sold, but first we have to wait for the assets to be sold, which could be years. It postpones the moment when the action could be started significantly.”

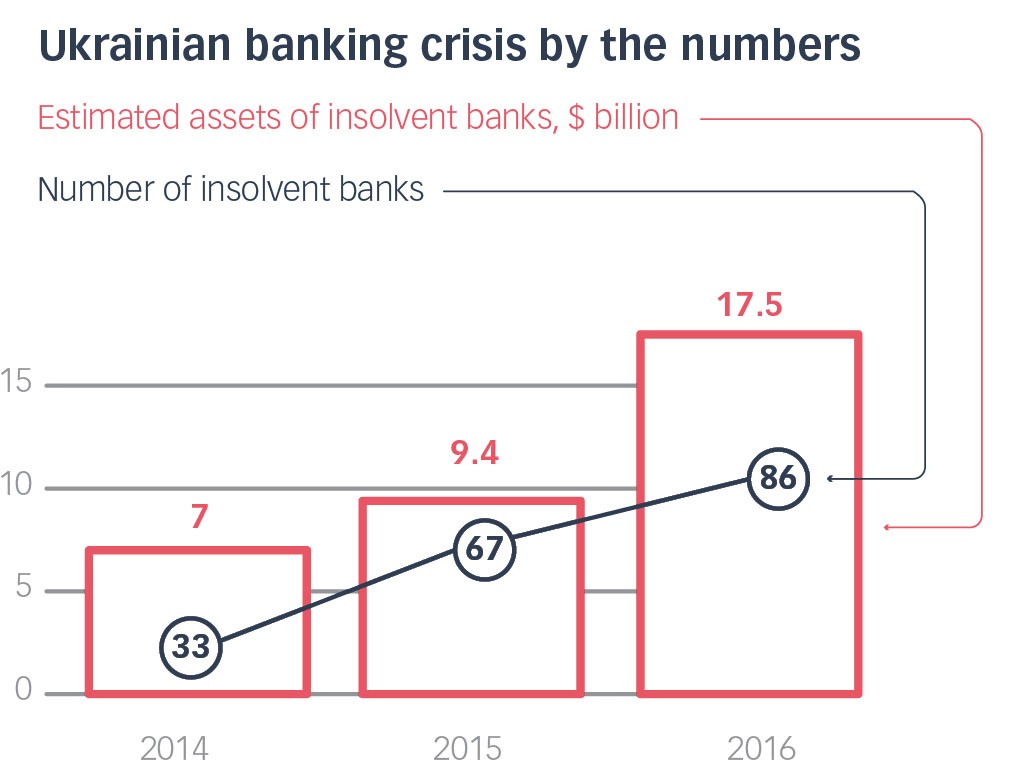

The number of insolvent banks has risen to 86 in the last three years, leaving Ukraine with less than 100 banks. (Sources: National Bank of Ukraine, Deposit Guarantee Fund)