When the product kills, is there any point in talking about corporate social responsibility for the peddlers of the product?

In the case of tobacco companies, public health activists say no.

“Corporate social responsibility is nothing more than a way for tobacco companies around the world to cover their tracks as they devote vast resources to getting people — including youth — addicted to their deadly products,” said Mark Hurley, director of international communications for the Washington, D.C.-based Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “Ultimately, these activities are nothing more than a way for tobacco companies to seek favor with policymakers and government officials and increase their credibility with the public. At the same time, they are supporting these popular corporate social responsibility programs, the tobacco companies are devoting vast resources worldwide to marketing and selling tobacco products that will kill one billion people worldwide this century unless governments stand up to the tobacco industry and implement the policies that have been proven to reduce tobacco use.”

Smoking kills

In Ukraine, tobacco companies have until recent years enjoyed a very friendly environment in which to aggressively market their cancer-causing products, with sales that drove smoking rates in Ukraine to among the highest in the world.

In the early years of Ukraine’s independence, tobacco products were promoted heavily in advertisements, point-of-sale locations like street kiosks and by street vendors. The tobacco industry also found ways to get its proponents into key places in government and into politics.

All the major tobacco companies have production plants in Ukraine and make more cheap cigarettes than are consumed domestically, sparking rampant illegal smuggling abroad to countries with stronger public health policies.

But the situation has improved as Ukraine, which joined the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in 2006, began adopting the major tenants of tobacco control in the last decade. Those include higher taxes on cigarettes, advertising bans, a ban on smoking in public places and public education campaigns.

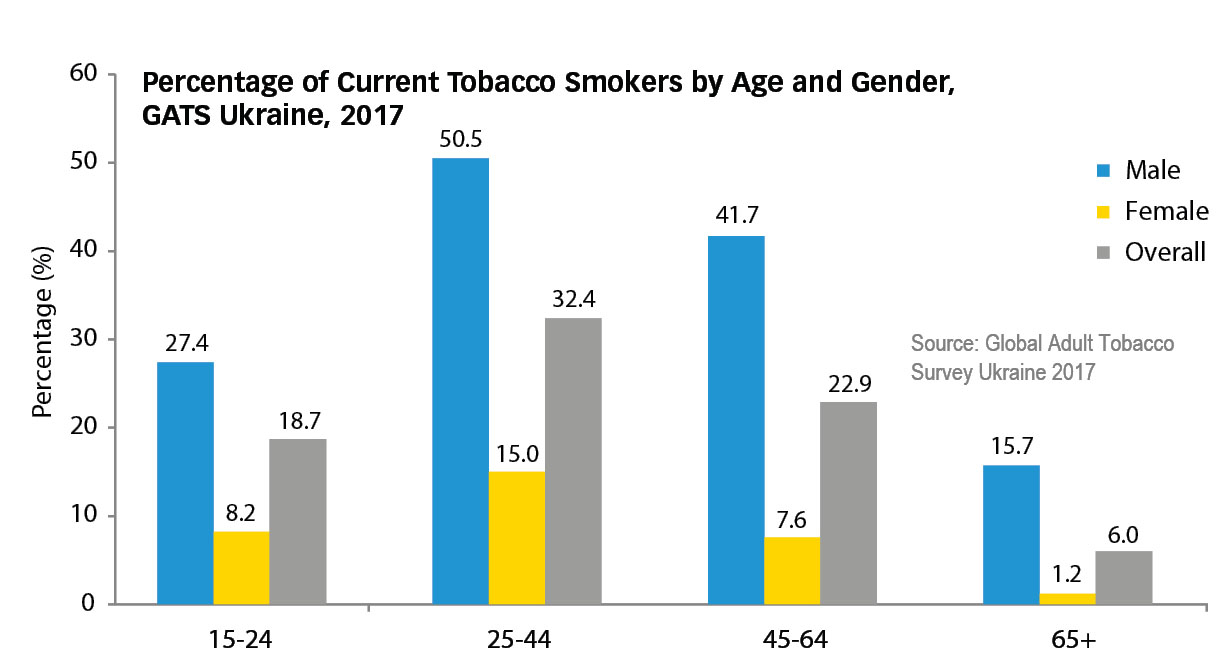

According to the Global Adult Tobacco Survey in 2017, daily smoking prevalence in Ukraine has decreased from 25 percent in 2010 to 20 percent in 2017. Still, cigarette consumption per capita remained the 18th highest in the world in 2014.

While the situation has improved, the nation still has among the cheapest cigarettes in the world, with most brands selling for less than $1 per pack. Ukraine has weak national programs to help smokers break their addiction, something most smokers want to do.

Consequently, in Ukraine, 45 percent of men still smoke, contributing to early death. Ukrainian men have a life expectancy of only 66 years, ranking a miserable 120th among nations, according to the WHO.

“Smoking is estimated to be the cause of 24 percent of all male deaths and of about 40 percent of male deaths from cancer. These numbers are shocking and entirely preventable,” Joshua Abrams, director of the Eurasia region at the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, said.

Oksana Totovytska, media manager at the Life Regional Advocacy Center, said that “every year in the world, 7 million people die from illnesses caused by smoking; in Ukraine this figure reaches 85,000.”

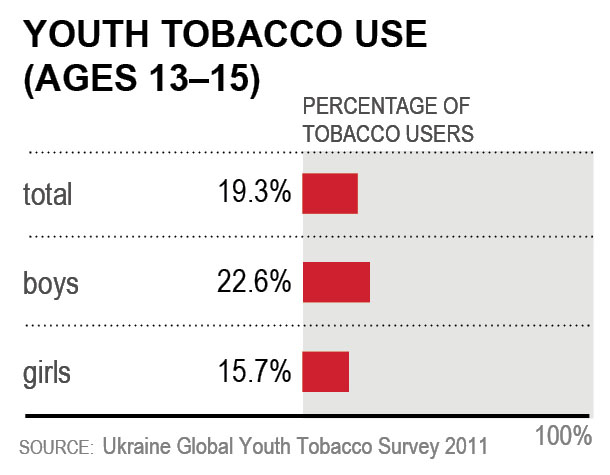

Targeting kids

Besides cigarette prices that are still too cheap, a legal ban on smoking in public places is incompletely enforced in Ukraine.

Additionally, flavored and colorful cigarettes are promoted in marketing campaigns aimed at enticing young people to smoke.

Besides lobbying, the tobacco companies also “engage in deliberate marketing practices to target kids,” Abrams said.

A report on tobacco marketing at point-of-sale locations in Kyiv, done by the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, found that “varying interpretations of the advertising and promotion ban at the point-of-sale have resulted in the incomplete enforcement of the law, allowing the tobacco industry to continually expose children to marketing.”

Laws on point-of-sale cigarette advertising are weakly enforced in Ukraine, allowing tobacco companies to market their products to children.

The report’s authors wrote that “this study demonstrates that harmful tobacco products and advertisements are present in areas that are visible and accessible to minors.” It details how price tags cover health warnings on packs, how cigarettes are placed near sweets and ice cream and displayed with colorful backgrounds.

Furthermore, “out of the 372 supermarkets, convenience stores, and kiosks that sold tobacco products, 84 were located within eyesight of a school,” the report reads. Studies have shown that “exposure to tobacco product advertising and promotion increases the likelihood that youth will start to smoke.”

Raising taxes

Totovytska, however, said that tobacco taxes have risen by 40 percent in 2016 and in 2017, expected to generate at least $2.8 billion in government revenue over the two years.

Other victories included getting Ukraine in 2015 to drop a lawsuit against Australia over plain packaging of tobacco products, eliminating another source of marketing for tobacco products.

The Framework Convention on Tobacco Control forbids tobacco companies from publicizing their corporate social responsibility. Instead, they show they are “giving back” to charity. Philip Morris, for instance, donates to charities and nongovernmental organizations in Ukraine, some of which are associated with health, despite FCTC guidelines that prohibit such activities.

Konstantin Krasovsky, head of the tobacco control unit at the Ukrainian Institute of Strategic Research at the Department of Health, said the desire to make money is behind philanthropy.

Tobacco companies “are owned by numerous stakeholders and this case they can have only one common interest: money,” Krasovsky said. The real aim of all charitable contributions, he said, is to delay or weaken effective tobacco control legislation to prevent or slow down tobacco use reduction.

Stop selling product

Krasovsky said that Philip Morris supports “only those entities which can give them political dividends.” For example, the Health for All Foundation is headed by a former member of parliament who several times submitted draft laws to weaken or delay tobacco control laws in Ukraine, Krasovsky said.

Krasovsky agrees with the World Health Organization that there is “an inherent contradiction” between tobacco companies and corporate social responsibility.

Totovytska said that if tobacco merchants were truly socially responsible, they’d stop selling cigarettes, which “kill more than half of their users. No other legal product causes so much human and economic loss. Any measures taken by cigarette manufacturers in the context of corporate social responsibility are very controversial. That is why such activities in Ukraine are prohibited at the legislative level. The only thing the tobacco industry can do to improve the development of society is to abandon the production of its own fatal product.”

Tobacco-control laws have cut smoking rates in Ukraine, but Ukrainians still smoke a lot, prematurely killing 85,000 people each year. Cigarettes also remain cheap by Western standards, making the problem worse.

Abrams of the Campaign For Tobacco-Free Kids said that big tobacco companies exploit poorer countries like Ukraine as it becomes harder for them to peddle their deadly products in the West.

“As more countries around the world restrict how tobacco companies can market cigarettes, we see tobacco giants like Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco aggressively targeting low- and middle-income countries. Most of the world’s smokers live in low- and middle-income countries — places that can often ill afford the devastating social, economic and health burden caused by tobacco use. Such is the case in Ukraine,” Abrams said.

Lobbying lawmakers

One tactic is lobbying lawmakers: “We know the industry is using their influence to block or delay tobacco control bills in parliament,” Abrams said, citing a Transparency International anti-corruption investigation, which uncovered links between lawmakers on the tax and customs committee and tobacco companies.

According to the Transparency International report: “The Committee on Taxation and Customs Policy, including its chair, Nina Yuzhanina, as well as Maksym Kuriachyi, Mykhailo Kobtsev and Taras Kozak have close ties with tobacco companies… The (members of parliament) promote initiatives and regulations in the interests of profitable tobacco companies and actively criticize and disregard bills which are unfavorable to the tobacco corporations. For instance, some of these companies, acting through the Committee, tried to introduce lower tobacco taxes.”

Serhii Mytkalyk, who investigated potential conflicts of interest for Transparency International Ukraine, explained to the Kyiv Post how members on the tax and customs committee have stalled two draft laws intended to bring Ukrainian anti-smoking legislation into line with European Union standards for the past two and a half years.

The draft laws included measures to increase the size of graphic warnings on cigarette packs and stiffen penalties for not enforcing the ban on smoking in public places.

Some politicians and civil servants who featured in the investigation are linked to tobacco companies. For example, the daughter of Mikhail Kobtsev, a member of the tax and customs committee, works for Philip Morris International. He uses Facebook posts to argue the tobacco industry’s case against plain cigarette packaging.

However, Transparency International did not uncover concrete evidence of wrongdoing and the politicians remain in their posts. “It’s really hard to prove the influence of an MP on a draft law… And the corruption is hidden. The civil servants and politicians are bought with money we can’t trace. Influence may also come in the form of privileges,” Mytkalyk said.

When asked about his company’s attitude to the proposed legislation, Oleksii Kalynichenko, a spokesman for Philip Morris Ukraine, told the Kyiv Post that “there is no consensus government position on this proposal which came from a group of MPs.”