Despite being one of the oldest forms of public transport, trams are seeing a comeback in the cities of Europe and Ukraine, opening up opportunities for Ukraine’s domestic tram producers.

As automobile use increased in the years after the World War II, tram networks in many European cities went into decline. But the success of the car has, conversely, led to congested city streets and calls for renewed investment in public transport. Trams are now proving a popular answer to many cities’ transport problems.

Tram networks still operate in 23 Ukrainian cities. Much of the rolling stock dates from Soviet times, and is so dilapidated that it needs urgently to be replaced with modern vehicles. In Ukraine, two domestic producers – Electron and Tatra-Yug – are developing new designs to satisfy domestic demand for the vehicles. But they also face stiff competition from foreign tram producers.

Although trams are less flexible than buses, running on tracks and taking up space on roads, they are an economic public transport solution for cities with high groundwater levels, where underground railways would be too expensive or impractical to build.

And with many cities in Europe restricting or closing off completely car access to their centers, trams are an ideal way to fill the transport gap – quiet, efficient, and producing low or zero emissions.

For instance, in Lviv, a western city of 720,000 citizens located 530 kilometers from Kyiv, tram routes cut across the city center, where entry to other modes of transport is closed.

Besides being economic and environmentally friendly, trams are less dangerous for passengers than both buses and cars. In the United Kingdom, 12 times fewer injuries occur on trams than on buses, according to a recent BBC report.

Tatra-Yug trams

Built on Czech know-how, Ukrainian tram manufacturer Tatra-Yug now produces several tram models that are 95-percent constructed from Ukrainian-made parts.

Tatra-Yug is an offshoot of state-owned aerospace manufacturer Yuzhmash, which set up the company after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting decline of the space industry. To reorient production from spacecraft and rockets, Yuzhmash sent some of its aerospace engineers for six months of training to the Czech tram producer Tatra, where they learned about tram manufacturing. The company then obtained permission to produce trams under license.

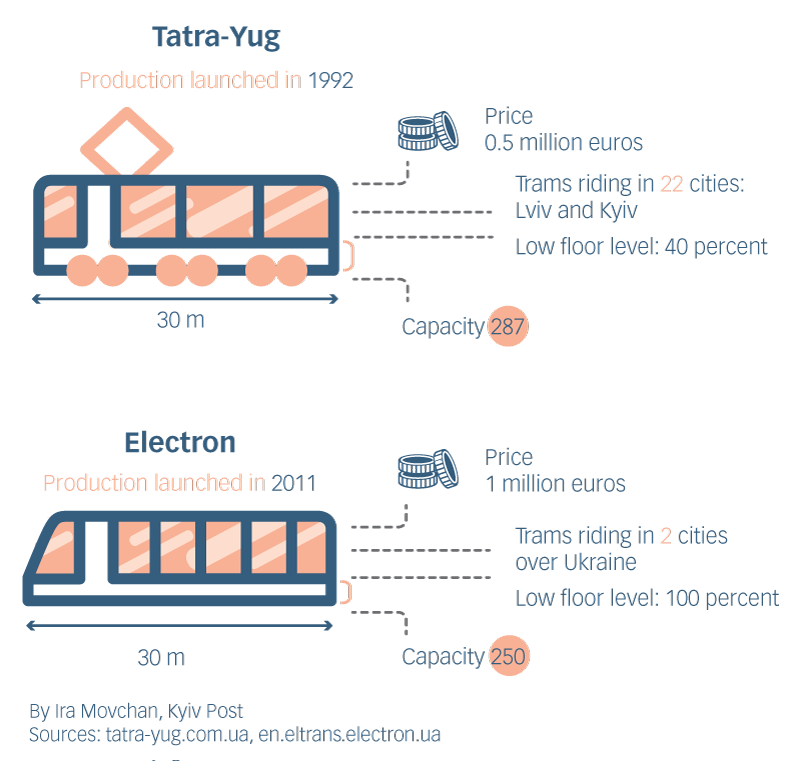

Today, Tatra-Yug’s trams operate in 22 Ukrainian cities, mostly in Kyiv and in cities in eastern Ukraine. The company’s head, Anatoliy Kerdivara, says that the quality of Tatra-Yug’s vehicles is so high that they rarely need repair. Its first two trams, produced by the company in 1994, have been operating in Kyiv without having to be repaired to this day, he says.

One of the main advantages of locally produced trams is their low price – one Tatra-Yug tram costs 500,000 euros, which is six times less than a new tram made by Czech vehicle producer Skoda.

But despite all the advantages, the Ukrainian company is losing out to foreign competition. This year it failed to win a tender held by Kyiv’s transport enterprise, which opted instead to buy 10 trams made by Poland’s Pesa at a cost of 11.5 million euros. Meanwhile, Tatra-Yug hasn’t sold a single tram all year.

Kerdivara can’t understand why, in times of economic crisis and war, Ukrainian transport companies still don’t buy Ukrainian.

“While we’re in such a deep crisis in Ukraine, budget money is going abroad to purchase trams there,” Kerdivara says. He adds that the production of Tatra-Yug trams not only gives jobs to local workers, but provides work for 250 domestic manufacturers who supply parts.

However, the picture is not all bad: by the end of 2016 the company plans to present its latest tram model – a 210-passenger capacity vehicle with a low floor that has been adapted to run smoothly on poor-quality tracks. Kerdivara also says he’s expecting a final decision on an order for trams from abroad – although he won’t name the potential buyer.

Low-floor Electron trams

In Lviv, the newest tram route connecting Sykhiv, a distant district of the city, with the city center was launched in November. The route operates with seven low-floor trams produced by local Ukrainian-German company Electrontrans, a subsidiary of the Electron Corporation. To supply the new route, the local producer won an international tender financed by European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, beating competing bids by Polish and Romanian tram manufacturers.

Electron produces low-floor trams 30 meters in length with a capacity of 250 passengers. The CEO of Electron Corporation, Yuriy Bubes, says that 70 percent of parts of the trams are produced in Ukraine. For instance, the tram’s engines are made in Kharkiv, and its air conditioners by another Electron enterprise. Those parts that are difficult to obtain on the domestic market are ordered from suppliers in Poland and Germany.

An Electron tram costs 1 million euros, while the average price of a European-made vehicle is around 2 million euros. Besides nine trams now operating in Lviv, two vehicles have been in use in Kyiv since the manufacturer launched production in 2011.

Besides supplying the domestic market, Electron plans to take part in tenders abroad. To do so, the manufacturer has to undergo technical assessments and obtain certificates for each country, Bubes says. Electron’s CEO is also planning to provide technical services for the vehicles it hopes to sell in Europe via a Ukrainian-Polish subsidiary company it has set up.

However, the operation of low-floor trams means cities have to repair existing rails, or build new tracks, which could limit sales possibilities in Ukraine. Another problem is the use of different track gauges – Electron has to produce three different versions of its trams for the Lviv, Kyiv, and European markets, all of which have different track widths.

But once in operation, the tram is easily accessible for people with disabilities. Unlike in other trams, which at most have low floors at their doorways, and raised passenger seating areas, wheelchair users can move from one end of Electron’s 30-meter-long vehicle to the other thanks to its single-level low floor.

According to Bubes, the company has received lots of positive feedback about his company’s trams from people with disabilities. He says every Ukrainian city should switch to using Electron low-floor trams.

“You should see the happiness of our Sykhiv residents – their life has changed,” Bubes says of the new line in Lviv with Electron trams.

“They (citizens) deserve proper transport conditions.”