It seems like everyone in Kyiv knew him — or at least every visitor to the InterContinental Hotel over the last four years. Its general manager, Jean Baptiste Pigeon, the white-haired hotelier with a ready smile and a habit of getting know people by name, would often greet people in the lobby.

The hotel lobby offers telltale signs, so Pigeon pays special attention. “The moment you enter a hotel and see the lobby, you know the ambience and how a hotel is performing,” Pigeon said.

Pigeon moved on in December to enemy territory, at least in the view of Ukrainians.

He’s now working in Moscow, where he will next year open a Crowne Plaza for the Intercontinental Hotel Group, a chain that’s taken him to such workplaces as the Ivory Coast, Portugal, Greece, Belgium, Tunisia, Lebanon and Jordan.

He’s also worked in his native France and, besides French, the languages in his repertoire include English, Spanish and Portuguese. “I found Russian difficult and Ukraine even more,” Pigeon told the Kyiv Post in an exit interview before taking on his new assignment.

Jean Baptiste Pigeon, general manager of the InterContinental Hotel in Kyiv, moved on to a new assignment in Moscow in December. (Courtesy)

On to Moscow

He has no problem with the transfer to Russia, which has been waging war against Ukraine for four years, at a cost of 10,000 lives and 5 percent of its territory.

“I am not coming as French. I am not coming as an old Ukrainian friend. I am coming as a professional hotelier. A hotelier has no religion, no political opinions.”

It’s just another stop on the journey for the well-traveled married father of three daughters.

“I have been an expat all my life,” Pigeon said — or most of it at least: He has lived in France only 14 of his 57 years.

“I grew up in Mexico, studied in Switzerland, did military service in Germany. I started with InterContinental almost 35 years ago. This is my 15th hotel in 11 countries.

He chose the hotel business because “I wanted a job that would provide me with an opportunity to travel,” Pigeon said. “I had that sense of sociability.”

He found all of that and more in Kyiv, a comfortable place to live, with his work only a 12-minute walk from his home.

“Living in Kyiv is so easy. It’s a small city. It’s still very affordable. You have an expat community and locals who are very open-minded, so you manage to mingle with everybody. I felt very at ease. I never felt in danger here.”

The InterContinental Hotel in Kyiv that he started managing in January 2013 opened in October 2009, entering the high-end market after the Hyatt Regency, Premier Palace and Opera Hotel, but before the Fairmont Grand Hotel and the Hilton Kyiv.

“We had the luxury product that Kyiv needed,” he said.

While Pigeon wouldn’t talk specific numbers, he said the luxury property — with 272 rooms, 11 floors and a magnificent rooftop terrace — has always made money, even during the grim years of 2013–2014, which combined revolution, war and recession in Ukraine.

“Everyone suffered,” he said of those two bleak years. “The five-star category was running at 35 percent occupancy.”

Hotel ‘oversupply’

In the hotel industry, it’s all about the average daily rate, or ADR, and revenue per available room, or “revPAR,” in industry parlance.

JLL, an international real estate and investment management firm with an office in Kyiv, says that Kyiv’s 128-hotel industry rebounded in 2017, thanks partly to such events as the Eurovision Song Contest in May.

In the first half of 2017, JLL said the average daily rate hit $147, while “revPAR” reached $67, the highest since 2013, when it reached $103, JLL said.

But, as Pigeon noted, average occupancy remains under 50 percent and “today we still have an oversupply” of hotels in Kyiv.

More competition arrived in 2017 or will soon — at least in cheaper categories — with the addition of 160-room Mercure Congress (Accor), the 192-room Park Inn Troitskaya (Rezidor) and the 312-room Aloft Kyiv (Marriott/Starwood), according to JLL.

Hard to corrupt tourism

But despite Kyiv’s comforts, Ukraine still has not developed its tourism industry, much to the dismay of Pigeon and to the detriment of the nation’s economy.

In many nations — France, Egypt and Turkey among them — tourism is a large part of the nation’s economy. In 2016, the World Travel & Tourism Council found that Ukraine ranked only 156th of 185 nations in the industry’s contributions to the gross domestic product.

While Ukraine counts more than 10 million international arrivals each year, the number is deceptive because many are simply crossing the border regularly, sometimes daily, for work or trade, rather than tourism. Yet they are counted as visitors.

“We have no serious tourism and it will not come tomorrow. The obstacles are numerous,” Pigeon said.

When he arrived, “there was no tourism policy on the agenda of the government — old or new. Nothing.”

Pigeon is a friend of Taleb D. Rifai, secretary general of the United Nations World Tourism Organization.

After organizing a meeting at its headquarters in Madrid, Pigeon helped persuade the Ukrainian government to establish the National Tourism Board with a modest annual budget of $180,000. “It might be a small step, but it’s a step,” he said.

“There is no political will. There is no political understanding of the positive impact of tourism.” Oligarchs and politicians want to preserve their advantages, leading to such competition-killing distortions as market dominance in the airlines industry by billionaire oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky’s Ukraine International Airlines.

“Of course we have a monopoly. The failure of Ryanair shows how politicians can interfere in commercial decisions,” Pigeon said, citing the decision of the low-cost Irish carrier not to enter the Ukrainian market after being unable to come to terms with Boryspil International Airport.

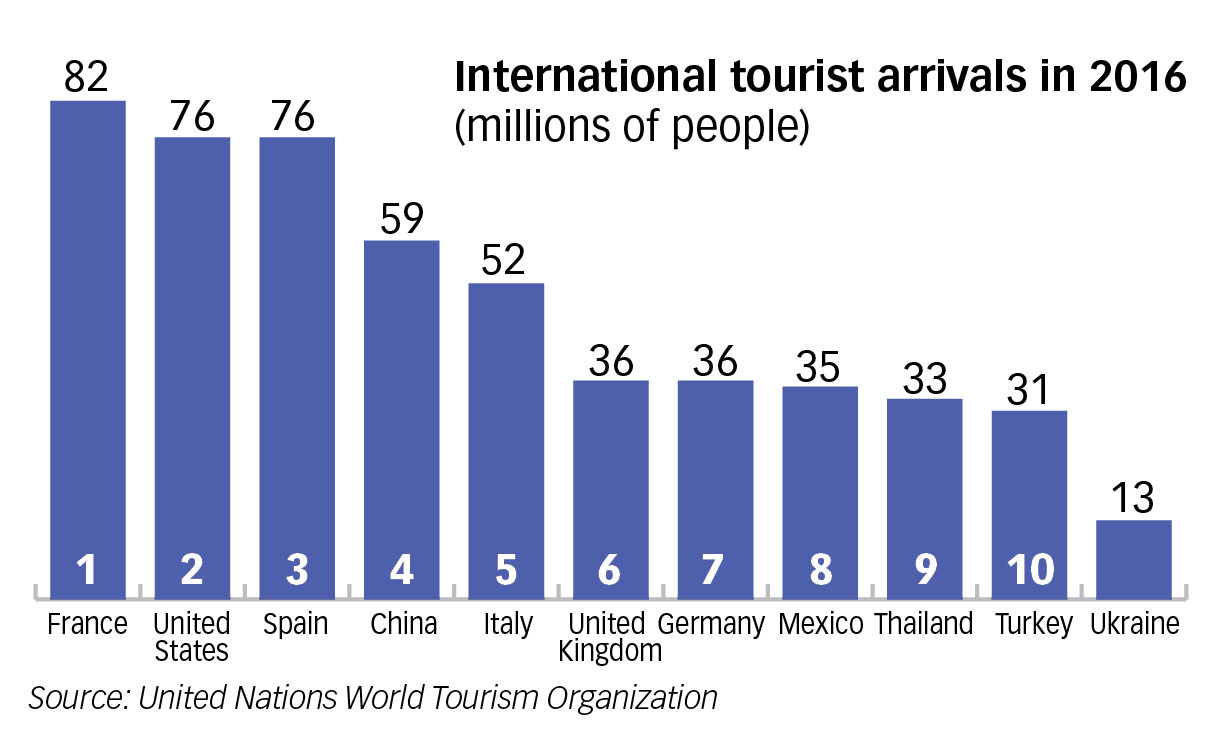

“It shouldn’t happen,” Pigeon said. His native France “is the perfect example” of a nation with a highly developed tourism industry that attracts at least 75 million visitors each year.

“If France can do it, why cannot Ukraine do it? Ukraine has beautiful landscapes, history, architecture, beautiful people, beautiful food. There’s no reason why Ukraine shouldn’t become Eastern Europe’s tourist destination. It will take 5 to 10 years, then it will become like Prague and Bucharest and Budapest.” Pigeon said that “tourism has a global impact and provides tax revenue for the country. It’s difficult to get ahold of it. It’s difficult to corrupt tourism. Tourism cannot be monopolized.” And that, he said, may be one reason why Ukraine’s politicians aren’t interested in developing the industry.

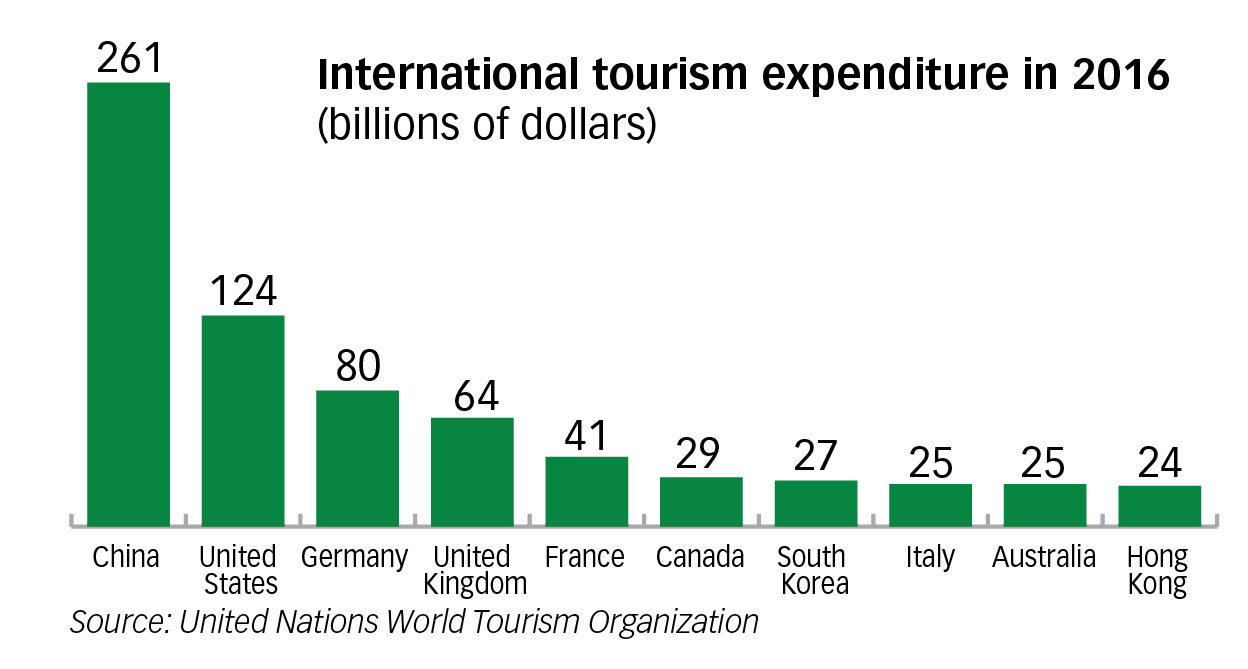

While France attracts the most tourists annually, Chinese tourists abroad are the biggest spenders. Ukraine is not even among the top 10 tourist destinations in Europe, according to the United Nations World Tourism Organization.