The new German ambassador to Ukraine, Anka Feldhusen, speaks Ukrainian and dances the Argentinian tango. While this is her first ambassadorship, she is far from a newcomer to Ukraine or the world of diplomacy.

From 1994–1997, she served as the head of the press section at the Germany Embassy in Kyiv. She returned as deputy chief of mission from 2009–2015, among other distinguished assignments. Before arriving in July as ambassador, she served most recently as a division head in the foreign relations department of German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier.

She also served as deputy chief of mission in Havana, Cuba in 2002–2005, missing, to her chagrin, the 2004 Orange Revolution that stopped Viktor Yanukovych from taking power in a rigged presidential election. Yanukovych would later win the presidency in 2010, and Feldhusen would be on duty in Kyiv for the 100-day EuroMaidan Revolution, which drove him from power in 2014.

In an interview with the Kyiv Post before Germany’s Unity Day celebration on Oct. 3, Feldhusen talked about her career, the bilateral relationship and Berlin’s policy priorities in Ukraine.

Love of languages

Why has Ukraine figured so prominently in Feldhusen’s career? She says it “was completely by chance.”

She grew up in Elmshorn, a northern German city of 48,000 people not far from Denmark. She loves languages — studying Latin, English and French — but became fluent in Russian early in life. She credits an exceptional teacher for that.

It was ultimately Feldhusen’s language skills that made her the top choice for her first assignment in Kyiv in 1994. In that assignment, she learned some Ukrainian. But she deepened her knowledge while serving as deputy chief of mission. Her Foreign Ministry allowed her to spend nine months studying Ukrainian exclusively.

“I can speak directly to all the people here,” she said of the benefits. “That is a great help. It makes things faster, more personal, more direct.”

‘Steps forward, back’

People who lived through the early post-Soviet years in Ukraine remember it as a brutal economic time for most people in the nation. Feldhusen served in Kyiv during the introduction of the hryvnia in September 1996, which coincided with a visit by then-Chancellor Helmut Kohl to Ukraine.

During her first stint, Ukraine also signed the Budapest Memorandum in 1994, adopted a Constitution in 1996 and, by the time she was reassigned in 1997, an oligarchy had started to form, which still plagues Ukraine today.

“The history of independent Ukraine is steps forward, steps back, steps forward,” she said. “Since 2014, we’re moving in a forward direction, (but) perhaps not as fast as all Ukrainians would like it.”

Living through the EuroMaidan Revolution triggered by Yanukovych’s refusal in November 2013 to sign an important political and trade agreement with the European Union, Feldhusen felt the popular fervor.

She and her son, who is now 17 and attends the German school in Ukraine, went to the rallies and were impressed by their size and strength from the start. She thought then that “Ukrainians will do it” and, despite ebbs and flows in the protests, Yanukovych finally fled on Feb. 22, 2014.

During those tense times, in which more than 100 people were killed by police snipers before the revolution triumphed, Feldhusen would escape to a dance studio on Luteranska Street to dance the Argentine tango.

“Dancing saved me during the Maidan and those workaholic times when we worked all night,” she said. “It makes you happy and fit.”

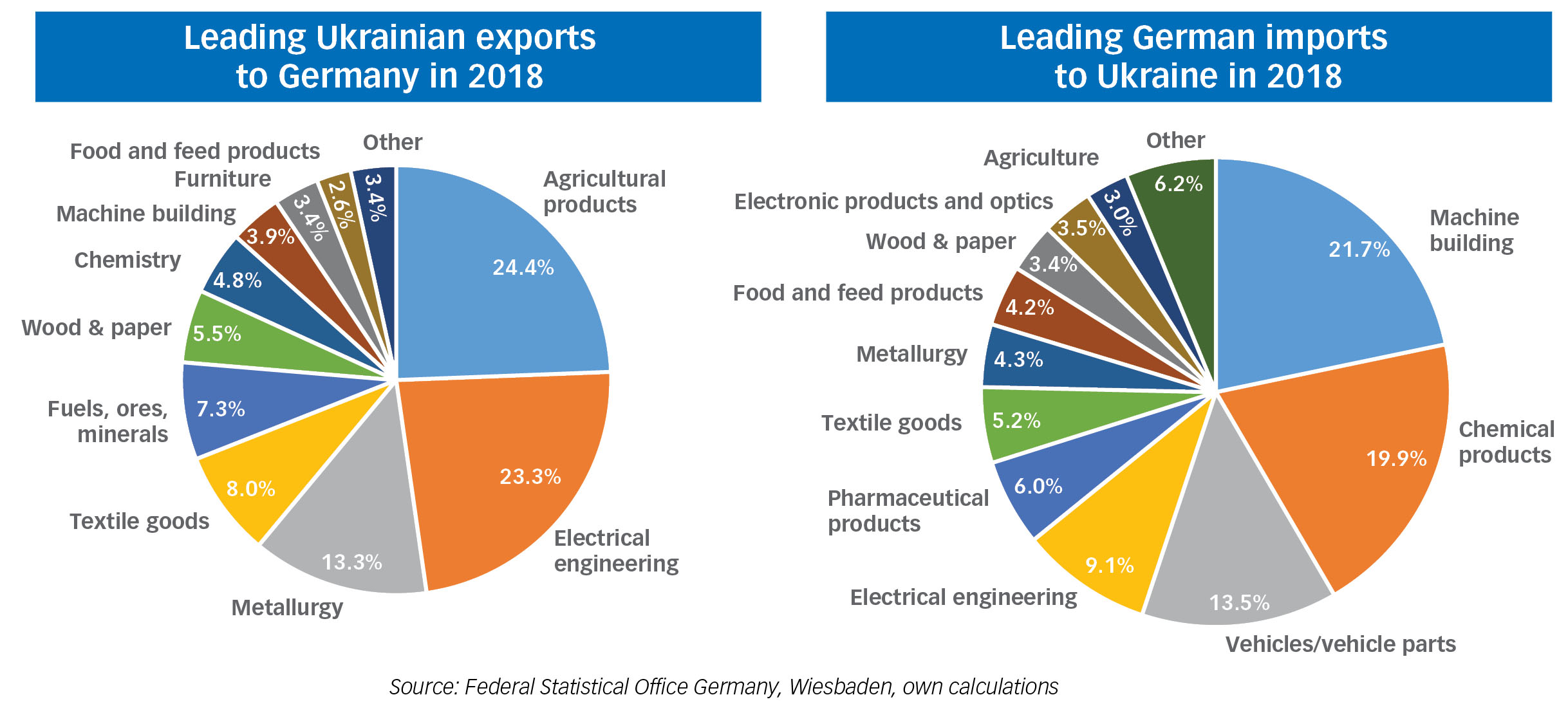

In the $8 billion bilateral trade relationship between Germany and Ukraine in 2018, Germany exports $5 billion while it imports $3 billion from Ukraine. Nearly half of Ukraine’s exports are agricultural products or automotive parts, while more than half of Germany’s exports are machine-building equipment, chemical products or vehicles and vehicle parts.

‘Steadfast partner’

The interview with Feldausen took place before the release of a memorandum reconstructing the July 25 phone call between Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and U. S. President Donald J. Trump, in which the two leaders criticize German Chancellor Angela Merkel for not doing enough for Ukraine.

Germany would dispute such characterizations, with officials in the past noting that the economic powerhouse of 83 million people contributes more than 20 percent of the European Union budget.

The EU has, in turn, allocated hundreds of millions of dollars in loans and grants to Ukraine since 2014. Additionally, on a bilateral basis, Germany has given more than $1 billion in assistance and more than $500 million in preferential loans in the last five years.

The interview also came before an anticipated new round of the Normandy Format talks involving Russia, Ukraine, Germany and France in an effort to bring Russia’s nearly six-year-old war against Ukraine to a halt. No date has been set yet for renewed talks.

Feldhusen said that Ukrainian fears that Germany will force Ukraine to compromise on its territorial integrity to achieve peace are unfounded.

“I think Germany has shown in the last five years that we have been a steadfast partner of Ukraine. We continue to be. We’re not putting pressure on Ukraine.”

She said that any settlement with Russia must be conditioned on the withdrawal of Russian troops from the Kremlin-controlled areas of the eastern Donbas, the re-establishment of Ukrainian control of its borders, and elections under Ukrainian laws. “It can’t be otherwise,” she emphasized.

She called the Sept. 7 exchange of 70 prisoners between Russia and Ukraine “a hopeful sign” that more progress is possible in achieving peace.

Russia’s war against Ukraine is far from Vladimir Putin’s only transgression against the civilized world. Putin is also blamed in the murders of thousands of Syrian civilians, the murders and attempted murders of critics at home and abroad, the ongoing occupation of parts of Moldova and Georgia and interference with democratic elections in Europe and the United States.

His record of destruction raises the question of what more he will get away with before he is treated like a pariah by the democratic community.

“It is a good question, one I have often thought about,” Feldhusen said. Her best answer is that “we need Russia to find solutions to these questions you mentioned, especially Syria. Russia helped to find a solution to the Iran crisis” over Tehran’s attempt to develop nuclear weapons.

She said “the subject of sanctions is something where people can talk about (it) for hours. We see where sanctions helped and where sanctions didn’t help at all. We have them right now (against Russia). Germany is very supportive of prolonging sanctions every six months in Brussels. By this, we have also shown very steadfast support of Ukraine.”

In the long-term, she said, democratic nations must do a better job of unifying around values that they are willing to defend around the globe.

A barge makes its way over the river Main in Frankfurt am Main, western Germany, as in background can be seen the city’s illuminated banking district on July 30, 2017. (AFP)

Nord Stream 2 reality

With the pipeline more than 70 percent complete, the $12-billion Nord Stream 2 pipeline — connecting Russian gas to Germany via the Baltic Sea — will become a reality, she said.

It doubles the capacity of the existing line to 110 billion cubic meters of gas yearly — all of which bypasses Ukraine’s land-based pipelines, through which most of Russia’s Europe-bound gas has traveled.

But Feldhusen notes that Merkel acknowledges “the political component” to what Germany regards as “a commercial project” and has worked to secure Russian guarantees to continue sending gas through Ukraine’s pipelines.

Ukraine receives transit fees that have reached $3 billion a year. Recent talks have floated the figure of 60 billion cubic meters of natural gas flowing annually through Ukraine’s pipeline from Russia, about half of the capacity of Ukraine’s system.

“We will need Ukraine’s pipelines for a long time,” she said. “Nord Stream 2 will be built and Germany is very much trying to help Ukraine continue sending Russian gas through its pipelines.”

‘Oligarch economy’

Feldhusen said that “the oligarch economy has always been one of the biggest problems in Ukraine” and that Germany supports the Ukrainian people’s drive for “a free market economy where the same rules apply to everybody.”

She said that how Zelensky responds to this challenge “is certainly one of the tests.”

In the battle against vested interests that have hampered Ukraine’s development, she said: “Germany will do its utmost to help Ukraine.”

This includes support for the independence of the National Bank of Ukraine, which led the nationalization of PrivatBank — the nation’s largest financial institution — after its former owners, billionaire oligarchs Ihor Kolomoisky and Gennady Boholyubov, allegedly stole $5.5 billion through insider lending.

Kolomoisky is now challenging the nationalization, which Germany considers to have been “the right decision,” Feldhusen said.

She also said that Ukraine needs to complete judicial reform, which made progress with a new Supreme Court and the formation of the Anti-Corruption Court under ex-President Petro Poroshenko. Only through establishing rule of law will Ukraine be able to attract enough investment to achieve prosperity, she said.

Her early meetings involving Zelensky, including one on July 24 as part of the G7 reform support group, have been encouraging, she said. She called the discussion lively and substantive.

“It’s a real discussion. It’s not just two monologues. It’s major progress.” Yet she cautions: “I think it’s too early to see what will come out of all the good intentions of this government.”