One of Ukraine’s largest agricultural companies is under attack from its former owners in a case that could prove to be a litmus test for how the government protects investor rights.

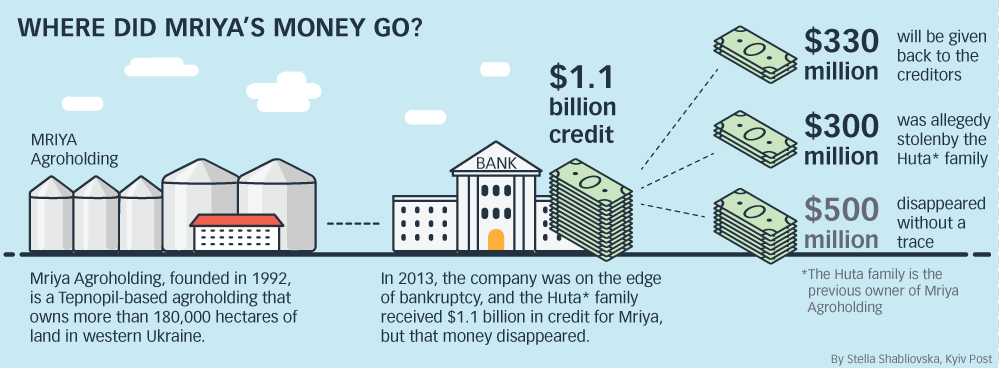

Mriya Agro Holding, which is on the path to repaying $1.1 billion in debts to foreign creditors, now faces an obstacle in the form of raider attacks from its former owners, who are suspected of mass embezzlement of foreign loans.

The raid

The morning of July 1, a group of armed men drove up to a Khorostkiv, Ternopil Oblast logistics facility belonging to Mriya Agro Holding. The assailants swarmed the business, and in spite of a legal counter-siege laid by Mriya’s ownership, the occupiers haven’t yet left.

“It was quite a shock,” said Simon Cherniavsky, CEO of Mriya. “It was the central base for all our trucking logistics.”

The raid was the latest dispute in the saga of Mriya Agro Holding, the Ternopil-based agricultural firm that controls more than 180,000 hectares of land in western Ukraine.

Mriya is attempting to fight its way out of $1.1 billion in debt via a restructuring plan that could see it pay off $330 million to creditors – the maximum that the company can afford to pay while staying in operation.

The company’s former owners – the Huta family, which absconded from Ukraine with at least $300 million in allegedly embezzled funds after cooking the company’s books in a way that attracted hundreds of millions of dollars in foreign investment – are now harassing the company through systematic raids on Mriya’s assets.

“The Huta family has enough power in Ternopil region, where most of the land is located, to block operations for the company and even seize some assets,” said Alexander Paraschiy, research head at Concorde Capital.

The Mriya issue has repeatedly been raised by foreign investors and businessmen as an example of the complete absence of creditor’s rights in Ukraine. Cherniavsky called resolving the restructuring and ongoing attacks by the former owners a “litmus test” for the government.

Deep in debt

Mriya was founded in 1992 by Ivan Huta and his wife, Klavdiya, as a farming conglomerate in Ternopil, 366 kilometers west of Kyiv.

Throughout the 1990s and through the 2000s, the company expanded, acquiring more land before going public on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange in 2008. By May 2013, Mriya had issued more than $400 million in Eurobonds to a range of international buyers.

But within a year, the company would be on the verge of collapse, with the Huta family preparing to flee the country.

Mykola Huta, the son of the founders, had become CEO, and had not been investing the loans and Eurobonds into developing the company. Rather, in a well-documented fraud, the money had been siphoned off to an offshore firm via sham contracts negotiated with related companies for supplies.

The Panama Papers release in April 2016 revealed a vast network of sham firms that the Hutas allegedly used to commit the embezzlement.

The company was audited by E&Y, but the firm appears to have missed signs that Mriya’s books were incorrect.

“There was some negligence,” Cherniavsky said, adding that Mriya management was uninvolved in discussions in the matter. E&Y did not reply to a request for comment.

Throughout the spring of 2014, the company began to fail to pay off its debts, and failed to pay interest on any of its bonds.

Andrei Pavlushin, the general director of OTP leasing, a Kyiv-based company that rents out agricultural equipment, said that payments from Mriya slowed in February of 2014 and totally stopped by August of the same year.

The company defaulted in August, months after the Huta family had already fled Ukraine, with Mykola Huta currently residing in Switzerland. He is the only family member facing criminal prosecution; as the others were not officers of the company at the time of the alleged fraud, they appear to have escaped liability.

Cherniavsky said it is difficult to estimate how much was stolen, but that “at the local level, everybody was selling, buying, stealing, funneling off small stuff, but on the scale of Mriya, that’s tens of millions of dollars a year.”

One estimate places the theft at $300 million, while the company was left $1.1 billion in debt.

Andriy Huta, another Huta son, did not reply to a request for comment. Mykola Huta could not be located.

Finding a way out

Since the Hutas fled, the company’s foreign creditors have managed to install their own representatives at the top of the company. After months of negotiations, Mriya reached a preliminary deal on Sept. 12 that would see the company pay back around $330 million of its debt – the maximum that it can afford to pay.

“It was a difficult decision for the creditors, but there’s no other scenario, as I understand,” said Pavlushin.

“Any other amount was not affordable by the company,” said Paraschiy, the Concorde analyst, before adding that ongoing attempts by the Hutas to take back the firm’s assets placed the deal in jeopardy.

On the day of the company’s August 2014 default, for example, prosecutors say that Mriya signed contracts allocating nearly Hr 300 million ($11.5 million) in equipment to firms controlled by associates of the family.

Mriya has yet to take back its occupied facility in Ternopil Oblast. The company had $2 million in inventory and hundreds of automobile units in the seized facility.

Taras Didyk, a former Mriya lawyer, spearheaded the raid. Didyk claims he owns the facility through a contract awarded to a company called “Global Feed.” A call to “Global Feed” was answered by a man who said he was unrelated to the company. Didyk did not reply to additional requests for comment.

Mriya’s options for solving the crisis are limited, said Rostyslav Kravets, a Kyiv attorney who specializes in corporate raiding cases. Kravets said that Mriya could go to court, but that any decision would be unlikely to be enforced.

Mriya has already received a decision in the matter from a Dnipro court, but cannot enforce it.

“All the state needs to do is apply the rule of law,” said Serhiy Ignatovsky, Mriya’s legal director.

Meanwhile, the Hutas seem to be making additional moves to muscle back into Ukrainian agriculture.

Ivan Huta has begun to register new companies. According to Ukrainian media reports, he has also met with local Ternopil oblast farmers in an attempt to convince them to work with his firm, promising “to attract foreign investors.”

Additionally, 60,000 hectares of land that Mriya claims was fraudulently sold remains to be taken back.

Cherniavsky says that the company intends to “push the Hutas to a settlement.”

“When you have sufficient evidence and sufficient pressure on an individual or on the family, we can push them to negotiate,” he said. “Everybody from the president down is aware of this issue and concerned that it be resolved within the law.”

He added: “We need support.”