When a Russian coast guard ship rammed a Ukrainian navy boat on Nov. 25 as it tried to cross the Kerch Strait from the Black Sea into the Azov Sea, it shook Ukraine.

Soon, Russia would have 24 Ukrainian sailors and three boats in its captivity. President Petro Poroshenko would call for 60 days of martial law and a potential delay in the March 31 presidential election, only to be checked by parliament, whose lawmakers would approve just 30 days of martial law in 10 regions.

This is a dispute long in the making.

Since May, after Moscow opened a bridge connecting Kremlin-occupied Crimea to the Russian Taman Peninsula, Russian coast guard ships have been stopping Ukrainian and international commercial vessels. The naval harassment has delayed many commercial liners headed to and from Ukrainian ports for hours and, sometimes, even days.

Consequently, companies and Ukraine’s economy face millions of dollars in losses. And events both in the Azov Sea and on the Ukrainian mainland — shipping interruptions, a flare-up of the war with Russia, and martial law — all can have broader economic implications.

“If there are further marine incidents, it could mean the closure of the Azov ports for shipping,” says Vitaliy Kravchuk, senior researcher at the Institute of Economic Research and Policy Consulting.

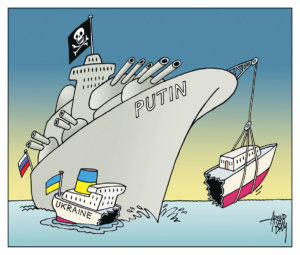

NEWS ITEM: Dutch cartoonist Arend van Dam illustrates the brute strength of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s military forces at sea, at least compared to Ukraine’s navy, in a cartoon after the Russian coast guard attacked three Ukrainian vessels on Nov. 25 and captured 24 Ukrainian sailors.

Industrial ports

Ukraine’s ports are vital and cargo turnover is high. In the first 10 months of 2018, the ports saw 683,800 units of 20-foot-equivalent container trade, a 16 percent increase on the same period in 2017.

In 2018, the Mariupol and Berdyansk ports, the two most important on the Azov Sea, received approximately 5 million tons and 1.6 million tons of goods, respectively.

They are now effectively blocked by Russia, with Ukrainian vessels being barred from leaving and entering Azov Sea. Currently, 35 ships cannot get to their final destinations, Infrastructure Minister Volodymyr Omelyan wrote on his Facebook page on Nov.28.

A total of 18 vessels cannot enter the Azov Sea from the Black Sea to get the ports of Mariupol and Berdyansk, and nine cannot exit the Azov Sea. Another eight ships remain moored in the ports. Only ships bound for Russian ports on the Sea of Azov are being allowed through the Kerch Strait by the Russian authorities.

“The actions of the Russians are clearly aimed at escalating the crisis in the Azov Sea, and to destabilize the region,” wrote Omelyan. “Russia hopes to drive Ukraine out of our own territory — territory that is ours in accordance will all relevant international laws.”

Two large Mariupol-based firms owned by billionaire oligarch Rinat Akhmetov — Ilyich Iron and Steel Works of Mariupol and AzovStal — are particularly dependent on the port in Mariupol to ship their finished goods to consumers. And besides steel, the ports are also critical export conduits for other top Ukrainian industries: agriculture and coal.

Any obstacles to shipping from these ports could hurt. Finding a substitute route won’t be easy, says Tymofiy Mylovanov, deputy chairman of the National Bank of Ukraine’s council as well as interim president of Kyiv School of Economics.

“The ports are critical, because our railroads are working at capacity and we have issues with cargo wagons,” he says. “There’s a real problem on the railroad.”

Without the Azov Sea, Ukrainian grain producers would have to transit their grain to other Black Sea ports like Kherson and Mykolaiv. As rail network is currently being used at full capacity, that would mean “more bad roads for residents of Azov Sea regions” as producers tried to ship goods by truck, researcher Kravchuk said.

According to his estimates, roughly 20 percent of Ukraine’s steel exports (or approximately 5 percent of total exports), and 5 percent of its grain exports pass through the Azov ports.

Continued trouble in the Azov Sea could lead Ukraine’s state railway company to invest in expanding its capacity. But that would take time. Without the ability to export Mariupol-made steel, the country could potentially lose $2 billion dollars a year, Kravchuk says.

Any further escalation would also threaten the grain industry. With the country expecting a record harvest, “any window that is closed for us means heavier pressure on our infrastructure, both seaport and railway,” Mykola Horbachov, head of the Ukrainian Grain Association, told Bloomberg on Nov. 26. “We are stretched to the limit.”

Should Moscow continue to block passage through the Kerch Strait long term, Ukraine could be in for an economic worst-case scenario, according to Yehor Kyian, an economic analyst at the International Centre for Policy Studies.

“With a full blockade, the (Azov) ports will lose up to $2 billion,” he says.

But barring increased naval conflict between Ukraine and Russia, that isn’t likely, according to Volodymyr Vakhitov, assistant professor at Kyiv School of Economics. The reason is that Russia is violating the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas.

The international community, by and large, continues to recognize Crimea as part of Ukraine and the Azov Sea is considered an internal sea. For this reason, Vakhitov does not believe Russia has any grounds to control access.

While there is no sanction for violating the Law of the Seas, Russia’s actions represent “a serious precedent,” Vakhitov says. “I don’t think many other countries would like to experience it.”

He believes other states could pressure Moscow to halt its actions, and that Russia does not stand to gain from continued violations.

Investment threats

On the evening of Nov. 26, the Verkhovna Rada voted to impose martial law in 10 border regions of the country for 30 days. The ultimate decision was a less expansive version of what Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko initially requested.

While it is unclear what martial law will mean in practice (and whether it will be noticeably different from the status quo), the combination of war footing and Russian aggression in the Azov Sea may worsen an already weak investment climate in Ukraine.

The country attracted a paltry $2.3 billion of the $20 billion of foreign direct investment it needed in 2017. This year economists project that the country will grow at a rate of 3.5 percent, but that could go down.

“None of the investors will risk putting money in a country that favors only military priorities, and where there is a risk of confiscation of property and deepening problems in relations between Ukraine and its neighbor (Russia),” said Kyian.

Ukraine must be ready for these economic side effects. However, over the last four years, the long-struggling country has not been prepared for such a scenario.

“Ukraine failed to lobby for its interests, negotiate with Western partners, and thus create an airbag that could minimize the negative influence of any worsening in the military situation,” Kyian said.

However, opinion is divided among experts.

Maria Repko, the deputy director of the Centre for Economic Strategy, sees a positive effect for Ukraine in the long-run.

Any escalation of the war has a negative impact on the economy and the investment climate in the short term, she believes. However, the goal of martial law is to focus the country on geopolitical problems, not just economic ones.

“In the long run, Ukraine as a country and Ukrainian business will triumph over the current economic processes,” she said.

Still, much remains unknown. And it will also depend on the reaction of private companies.

Andy Hunder, the president of the American Chamber of Commerce, said that his organization will be monitoring the situation closely.

“Many of (the companies) are waking up on a Monday morning and they are evaluating what the risks are,” Hunder told the Kyiv Post on Nov. 26. “It’s very early to give numbers on what the effects will be on companies themselves and the economy.”

On Nov. 29, his organization urged businesses to take a “business as usual” approach until further notice.

The International Monetary Fund also said that it will continue cooperating with Ukraine, a positive sign for strengthening business confidence.

But Elena Voloshina, head of the International Financial Corporation’s representative office in Ukraine, says that the martial law still scares off investors, despite the IMF reaffirming its support.

“The words themselves and uncertainty are frightening, because we don’t understand what is behind the law,” Voloshina told the Kyiv Post. “The IMF is certainly a beacon and everyone is looking at it, but this does not mean that all private investors will be guided by it, since they have their own policies.”

Oleksiy Feliv, managing partner at legal firm Integrites, views the imposition of martial law as a purely political decision, underscored by the fact that the duration was cut in half to 30 days.

“Indeed, the red signal for business and investors will be if there are (more) military actions,” said Feliv.

Meanwhile, former Agriculture Minister Oleksiy Pavlenko said that he sees no reason to panic. The economic situation now is much better than it was a couple of years ago, when Russia’s war against Ukraine was much more heated, he said.

“Ukraine’s bank reserves now are three times higher than in 2015, it has enough fuel for at least 2.5–3 months, and has full grain elevators,” Pavlenko said.