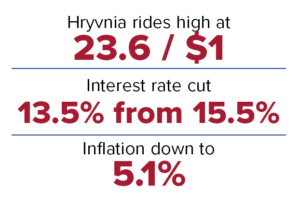

The Ukrainian national currency, the hryvnia, is still riding high, flying in the face of most predictions that it would depreciate against the U.S. dollar in the fall, as it usually does.

This trend accelerated a sharp decrease in consumer inflation, which hit 5.1% year-over-year in November. This means the National Bank of Ukraine has achieved its 2015 target of having 5% inflation by the end of 2019.

“Inflation has slowed down substantially as a result of strengthening the hryvnia exchange rate and improving inflation expectations,” the NBU wrote in a Dec. 12 statement.

The central bank responded by cutting the interest rate to 13.5% from 15.5%. It is the fifth rate reduction this year, after a reduction to 17.5% from 18% in April.

NBU Governor Yakiv Smolii said that the central bank is “accelerating monetary policy easing, as the hryvnia’s sharp appreciation causes a faster reduction in inflationary pressure than we expected.”

The regulator is aiming to secure an interest rate of 8% by the end of 2021, as long as it can maintain a 5% inflation rate. The NBU is also increasing its purchases of foreign currency, having already purchased $5.5 billion this year thus far.

“I think it is clear now with the larger than expected rate cut, and now this commitment to increase foreign-exchange purchases that the NBU are now worried by the over-appreciation of the hryvnia brought on by a weight of capital inflows,” wrote Tim Ash, a Ukraine-focused London-based markets strategist for Bluebay Asset Management .

Strong hryvnia defies season

The Ukrainian currency hit Hr 23.69 per $1 on Dec. 11, according to the NBU, while a slew of financial analysts in late summer had predicted it to be above Hr 27 per $1 by now.

According to the central bank, a key factor was excessive foreign currency supply in the past several months, brought on by high export revenues, due to the record harvest of cereals and oilseeds and the sale of funds from foreign currency borrowings of state-owned companies.

Experts say the hryvnia usually falls relative to other currencies in the fall, when Ukraine imports energy and farmers need fuel to harvest crops. As the end of the year nears, the government plans its largest expenses. All this causes the hryvnia’s value to weaken. In the spring, farmers get revenues, boosting the currency.

“Something happened that had never happened before,” said Ruslan Chorniy, the managing partner of Financial Club, an independent banking market research firm, referring to the sudden break in the hryvnia’s seasonal trend.

Chorniy added that the lack of seasonality left agricultural exporters unable to profitably shed their foreign currency earnings, which contributed to the trend.

Psychology also plays a role in the hryvnia’s fluctuation: Everyone expects it to decline in the fall, according to Serhiy Fursa, the head of fixed income at Dragon Capital.

Hryvnia bond demand

The hryvnia has been gaining ground since the summer. A key reason was this year’s trend: Insatiable portfolio investors pouncing on hryvnia treasury bills in record amounts.

In the first 11 months of 2019, nonresident investors bought more than $4 billion worth of treasury bonds, chasing its extremely high real yield. The hryvnia was one of the world’s best performing currencies in 2019.

Ukraine’s deal with the international securities depository Clearstream, which greatly simplified the ability of foreigners to buy Ukrainian securities, also contributed.

According to the NBU, while demand remains high, it has become less of a factor behind the hryvnia’s appreciation in recent months.

Treasury bond demand “was a key factor,” said Oleksandr Paraschiy, head of research at investment firm Concorde Capital. “But we also see that the trade balance is much better than it was a year ago.”

Paraschiy said that lower oil and gas prices and less active Ukrainian importers contributed to the trend. Much will depend on the ongoing gas talks with Russia. If an agreement to transit Russian gas through or into Ukraine is reached, gas prices could fall even more and there will not be significant downward pressure on the strengthen of the hryvnia.

A blow to exporters

Financial analysts told the Kyiv Post that dashed seasonality expectations are a blow to Ukraine’s agricultural exporters.

Nikolay Gorbachov, president of the Ukrainian Grain Association, said last month that a stronger hryvnia hurts exporters, who often make deals against future expectations and receive lower earnings on exports.

“We have a negative trade balance,” said Gorbachov. “The strengthening of one’s own currency is more of a negative than a positive sign.”

Chorniy said that players in Ukraine’s agricultural sector were waiting for the hryvnia to decline in fall.

“Agriculturists are used to selling currency at a high rate. They waited for September when there will be a surge in the interbank market so that they would sell at a high rate,” he said. Their hopes were dashed when the hryvnia rate failed to fall and they were forced to sell their reserves haphazardly, which contributed to the current trend.

“We had a forum with agriculturists last week, and they confirmed our guess that they were trying to play with the rate expectations as usual and they lost,” said Chorniy.

NBU criticism

Bohdan Danylyshyn, chairman of the National Bank Council, cautioned on his Facebook page that a strong hryvnia combined with industrial deflation in 2019 could lead to enterprises or entire industries becoming unprofitable and reducing their production due to the rigidity of costs.

He also warned against the NBU leadership’s “orthodox inflation targeting,” overly strict monetary policy and avoidance of interference. He believes the hryvnia’s strength is not supported by economic fundamentals.

Protesters demonstrating outside the central bank over the past month have complained about the unusually strong hryvnia. NBU officials suspect that many of these protesters are paid for by central bank enemies, such as the Ukrainian oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky, who allegedly stole $5.5 billion from his bank, PrivatBank, before the NBU had to nationalize it. .

“They have received a roasting for management of monetary/exchange rate policy,” Ash wrote. “Perhaps now by responding to these complaints the NBU hopes some of this criticism will be toned down.”

In a Dec. 11 statement, the NBU defended the hryvnia’s flexibility, saying that Ukraine is significantly exposed to external markets and that artificially maintaining a constant hryvnia rate would cost tens of billions of dollars in international reserves.

“If the NBU, regardless of the real economic situation, did not allow the hryvnia to strengthen, but held the rate at Hr 26 or 27 per $1, what would business and the population think?” the central bank stated.

“They would perceive that the NBU is protecting this rate and, thus, the interests of certain interested parties. Then, trust in the NBU and the national currency would fall and everyone would prefer to invest in foreign currency, which would push the hryvnia into devaluation.”

Kyiv Post staff writer Natalia Datskevych contributed to this report.