Name: Olesia Kholopik

Position: Senior project manager at the Center for Democracy and Rule of Law

Key point: Ukrainian roads need to become a safer place

Did you know? Former head of the Students League of Ukrainian Bar Association

For some, rules and regulations are boring as hell. Olesia Kholopik is not among these people.

This young lawyer gets passionate when she talks about corporate policy, little-known laws and road regulations.

Two years ago she left Samsung Ukraine, her first job out of college, to join the Center for Democracy and Rule of Law, or CEDEM, a think tank in Kyiv.

Now Kholopik, 27, is coordinating the center’s advocacy campaign for road safety.

Even though working in corporate sector was Kholopik’s dream throughout her studies in the Academy of Advocacy of Ukraine, one of top 10 law schools in Ukraine, she says she never regretted leaving Samsung after two years for a think tank.

“Here I can really feel the change happening,” she says.

But even prior to joining CEDEM, Kholopik wasn’t a complete stranger to social activism. She got a taste of it when she joined, and then headed, the Students League of the Ukrainian Bar Association.

The youth organization of the Bar Association, the League organizes educational and social events and aims to integrate the students into the professional legal circles.

When she joined it in her second year of college, Kholopik’s first job was to fundraise for the league’s activities. It was 2009, and fundraising after the economic crisis was harder than ever.

Was she, a 19-year-old who just recently moved to Kyiv from a much smaller western city of Rivne, afraid to knock on the doors of the top law firms and ask for donations?

“No, not really,” she says.

The youth league of the Bar Association, she explains, opened many doors. Thanks to it, she got acquainted with the whole market of legal services in Kyiv while still being a student.

When she finished college, Kholopik left activism behind and headed for a legal specialist position in Samsung Ukraine. It was perfect for her: A stable well-paid job, a multinational company and a corporate environment where everything was regulated.

But three years later she was invited to join CEDEM, then known as the Media Law Institute, to lead an educational campaign for local activists in Ukraine’s regions.

It was a tough decision: to leave behind stability and great career prospects for a fixed-term contract in a think tank. But Kholopik took the risk, and in 2015 traded her office desk for the on-the-road life of a coordinator of a regional program.

In the new role, she had to travel to 16 of Ukraine’s 24 regions, organizing and sometimes teaching workshops for local changemakers.

A year later, as the program came to an end she switched to two new ones: road safety and monitoring court reform.

Change on the road

When the protagonist in a legal drama makes a final statement in a murder case, his eyes don’t sparkle half as much as Kholopik’s do when she describes the legislative flaws that undermine road safety.

Small fines and lack of control from the patrol police make for reckless driving. Speeding is ubiquitous, while seat belt use is rare.

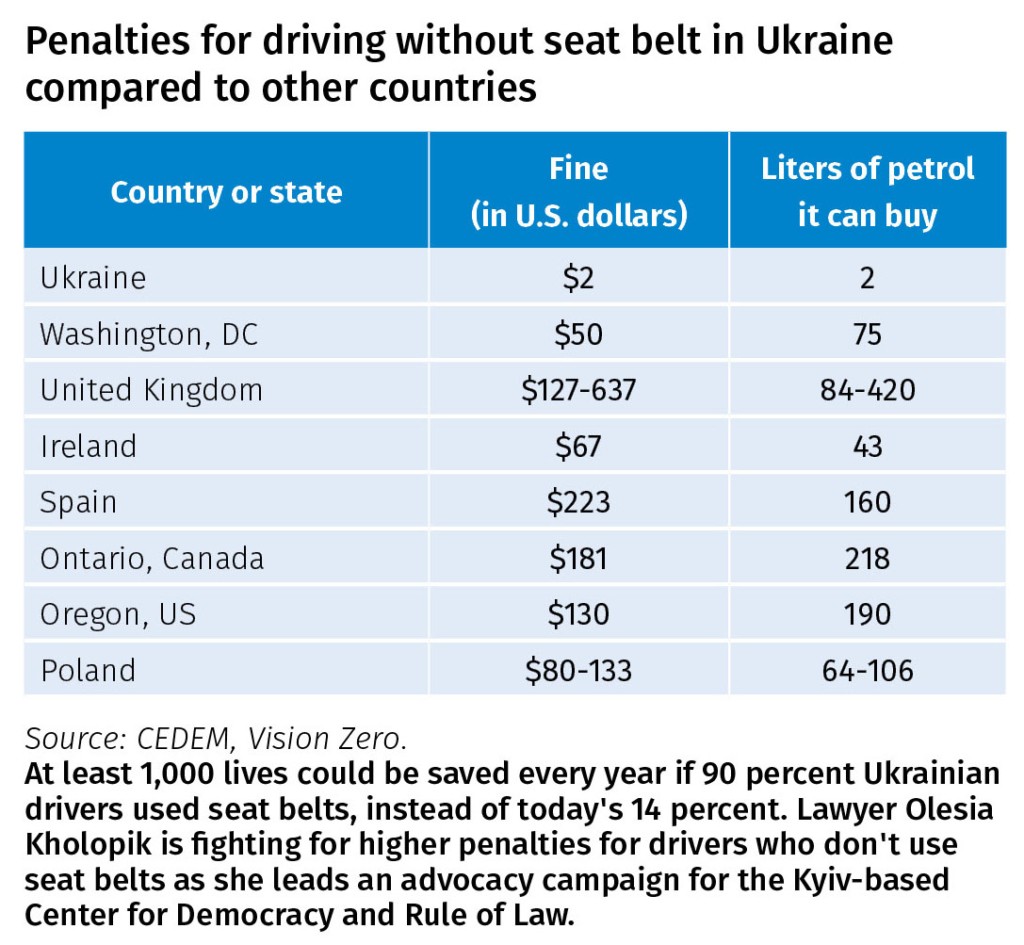

Only 14 percent of drivers in Ukraine and 34 percent in Kyiv use seat belts, CEDEM found out. Compared to 80-98 percent in the United States and most European Union countries, it shows just how little care for safety Ukrainian drivers have.

To trick the car mechanism that rings an alarm when the driver isn’t using a belt, Ukrainian drivers use special alarm stoppers, dummy clips, or even clip the belt behind the seat.

“I’ve heard so many myths about using a seat belt,” Kholopik sighs. “Some say it won’t save them in an accident, others say it leaves wrinkles on their clothes.”

If caught not using a seat belt, a Ukrainian driver would get a fine of just Hr 51 ($2). A driver from Spain would have to pay 200 euros.

Speeding is another issue. While the speed limit within Ukrainian cities is set at 60 kilometers per hour, almost no one sticks to it. The first problem is the so-called “unpunishable 20 kilometers”: Only by exceeding the speed limit by 20 kilometers or more might a driver face a fine.

And if a fine is imposed, it’s a light one. Speeding brings a fine of Hr 255-510 ($10-20). In the EU, the fines are several times higher, and speeding over a certain limit means drivers lose their license.

Throw in the fact that for the past two years there’s been nearly no speed control on Ukrainian roads. After the old, corrupt traffic police were shut down and replaced with the new patrol police, there was very little police control on the roads. Traffic cameras are promised to be introduced sometime in the future.

As a result, impunity rules the roads.

“Speeding is considered almost a norm,” says Kholopik, who is a newbie driver herself.

But there is a way to fight it, she believes. Traffic regulations need to be changed, and higher fines to be introduced. For example, Kholopik says, the fine for driving without a seat belt should be raised from Hr 51 to Hr 1,000 ($38).

“The idea is not to get a lot of money through fines,” she says. “The idea is for the fines to work as a prevention.”

In CEDEM, her job is to bring together every suggestion from every side – drivers, passengers, authorities – and boil it down into proposals of new regulations by autumn. Obviously, many drivers aren’t excited about bigger fines, so the discussion gets tense.

That’s not even all of Kholopik’s work. In CEDEM, she juggles two projects. Beside the road safety, she oversees “Chesno. Filter the court,” a campaign to monitor the selection of new judges for courts of each level that is part of the ongoing judicial reform in Ukraine.

The first results of the monitoring have been disappointing.

The Higher Qualification Committee for Judges that is vetting the acting judges has many times approved the judges who were vetoed by the Public Integrity Council, the body that analyzes the tax declarations, wealth, and past rulings of the judges, looking for the signs of corruption.

Kholopik hopes that the selection can improve if the society activates and starts watching it closely. So far, the process hasn’t gotten much of society’s attention. That is what Kholopik is trying to change.