When Ukrainian tech entrepreneur Eugene Shneyderis made his first bottle of wine, he didn’t think he would one day be a wine producer. In 10 years, Shneyderis’s Beykush winery has become a reputable brand that produces nearly 30,000 bottles of wine annually.

Paving its way from rural vineyards near southern city Mykolaiv to wine stores and restaurants in bigger cities wasn’t easy for a small firm like Beykush. For reference, Mykolaiv is located 480 kilometers south of the capital, Kyiv.

For years, local winemakers suffered from Ukraine’s extensive bureaucracy and lack of state support. Local customers didn’t believe that Ukraine could produce good wine and preferred popular European brands that are usually cheaper.

It discouraged Ukrainian entrepreneurs from investing in the wine business. As a result, only 130 local enterprises have a license to produce wine compared to over 46,000 in Italy. But those who decided to take a risk, try to stay optimistic about the future of the industry.

“Ukraine is perfectly adapted to make very good wine,” said Christophe Lacarin, a French winemaker who owns vineyards near Odesa, the Black Sea port city of 1 million people located 500 kilometers south of Kyiv. Ukraine’s southern regions have a favorable climate to grow grapes, while many local winemakers can turn the harvest into a high-quality beverage.

To support them, the government has to adapt laws to the needs of the small business, while Ukrainians need to be patriotic and start buying more locally produced wine, Lacarin said.

Unfair competition

When Ukrainians choose a wine for a date or a party, they would rather buy a bottle of Pinot Grigio from Burgundy than Sukholimanske from Odesa.

There is a stereotype, especially among the older generation, that “everything imported is better than local,” said Anna Gorkun, CEO of Inkerman winery and founder of 46 Parallel Wine Group.

Ukrainian wine stores are packed with European imports. On its website, the wine store OK Wine sells 519 bottles of Italian wine and only 57 bottles of wine produced in Ukraine; online store Good Wine has 3,151 bottles of French wine and only 75 bottles of Ukrainian.

The share of Ukrainian wine in big supermarket chains is decreasing too. In 2020, only 27% of wine in the Auchan chain of stores was Ukrainian and 26% — in Retail Group, which includes popular supermarkets Velyka Kishenya and Velmart. Compared to 2017, it’s a 6–10% drop.

In 2020, the Ukrainian wine market suffered from COVID‑19 and the record low grape harvest, according to Alexander Sokolov, CEO at analytical company Pro-Consulting. It was followed by a 20% increase in wine imports from Europe that hurt the industry even more, according to Sokolov.

The import went up last year because the Ukrainian government lifted import duties on wine from the European Union following the obligations the country undertook when it signed the association agreement with the EU in 2014. Ukraine imported $85 million worth of EU wine in 2016; in 2020, the figure soared to $180 million.

For foreign producers, supported with tax reliefs and state investment, Ukraine is a profitable market. It is easy to cross the country’s borders due to the zero import duty and the lack of strict control over the quality of the imported wine, said Volodymyr Kucherenko, head of Ukrvinprom, an organization that supports and protects the interests of local winegrowers and winemakers. And while domestic wine can compete with European in quality, it cannot outcompete it in price, Sokolov said.

Foreign producers, boosted by the government’s support, can sell a bottle of wine for $3 even when its cost of production is higher. Ukrainian producers sell good wine for $5–7 for a bottle on average.

Locals set higher prices for the same quality because they do not receive as much financial support from the state as European winemakers do, according to Lacarin.

The government should protect local producers, limiting the access of imported products to the county, according to Kucherenko.

“If there’s more Ukrainian wine on the shelves than imported wine, there is a chance that the situation will change,” Gorkun said.

Bureaucratic burdens

In the past, one needed to submit 140 documents to register a winery, a tedious and costly process that put small producers at a disadvantage.

Through the grueling process of registration, the government wanted to control the wine market and protect it from illegal producers. Such bureaucracy, however, only opened a door to corruption; law enforcers could pay a visit to a winemaker for the smallest mistake.

“One unnecessary step, one wrong letter on the excise stamp and you can be prosecuted,” Shneyderis said.

In 2015, local authorities accused Shneyderis of producing illegal wine and seized his equipment. After the incident attracted public attention, the tax service closed the investigation.

Lacarin spent nearly 10 years trying to get a license to sell wine in Ukraine. Following numerous requests, in 2018 Ukraine’s parliament simplified the process of registering a small or medium-sized winery — one that produces up to 100,000 liters of wine using grapes, berries, or honey it grows or produces itself.

It was a boon for small winemakers, Lacarin said. But now local businesses have to deal with another bureaucratic challenge — excise stamps, labels that prove that taxes were paid. Developed European countries do not have excise stamps.

“In the rest of the world, wine is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented grapes. In Ukraine, it is the product for which you can be prosecuted,” Shneyderis said.

The excise tax is laughable: $0.0004 per liter and also separately $0.007 for a stamp. Economically, it doesn’t make much sense. In 2019, the state spent over $800,000 to manufacture the stamps but got only $72,000 from the excise tax. But if winemakers make a mistake in the documents, they may face a huge fine.

“Wine is food. There is no logic in imposing an excise tax on food,” Gorkun said.

Annexed market

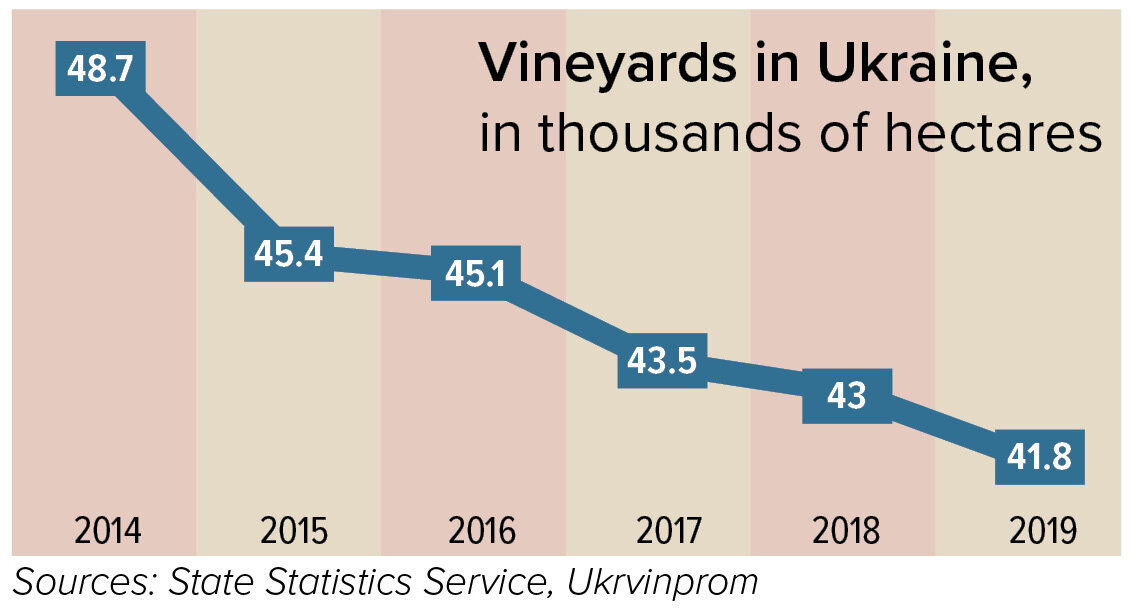

Rather than focusing on bureaucracy, experts said that the government should help local businesses to ramp up the production of wine that decreased dramatically after Russia’s 2014 invasion of Crimea, the major wine growing and producing region in Ukraine. According to Ukrvinprom, Ukraine lost 26,400 hectares of vineyards after Russia annexed the peninsula.

Apart from the grape supply, Ukraine also lost control over its finest vintage wineries, including Massandra, Novy Svit, Inkerman, Koktebel.

In January, Russia sold Crimea’s Koktebel for $1.4 million. In 2020, it sold Massandra for over $2 million to the subsidiary of Russia’s bank controlled by one of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s allies, Yuri Kovalchuk.

Gorkun’s Inkerman had to abandon three plants, cellars and 3,500 hectares of vineyards when the Kremlin invaded Crimea. At that time, Inkerman was the best on the local market and planned to expand abroad, and even start initial public offering. But the plans were canceled.

“Our main goal was to save the customer and the image of the brand,” Gorkun said.

To continue doing business in Ukraine, Inkerman registered a new company in Kyiv that now works independently from the Crimean firm. Inkerman lost a substantial share of its market because it could neither import grapes from Crimea nor sell its wine there. The company still controls nearly 8% of the market, producing nearly 4 million bottles of wine a year. Ukraine’s Inkerman doesn’t own any vineyards in Ukraine. Instead, it buys grapes from local farmers.

“There is no need to invest in our own vineyards,” Gorkun said. “We prefer to give the opportunity to develop and maintain production to those winegrowers who have already invested.”

Drinking culture

Last year Gorkun embarked on another venture — she launched a new brand of wine called 46 Parallel. It targets the younger generation.

“We believe that millennials and people born in the 2000s will be more tolerant to Ukrainian products,” she said.

Unlike their parents, born in the Soviet Union when the most popular wine was “sweet, cheap and heady,” millennials try to build a wine-drinking culture that would be more similar to the European one. They prefer dry wine to sweet or semi-sweet.

In the Soviet Union, when people wanted to buy wine, they were looking for something sweet and cheap. The new generation of Ukrainians is building a different drinking culture, which is more similar to the European one. They prefer dry wine to sweet or semi-sweet. (Kyiv Post)

The consumption of wine still remains small: One Ukrainian consumes 3.5 liters of wine a year compared to 62 liters in Portugal, 50 liters in France or 44 liters in Italy, according to Ukrvinprom.

These countries have a centuries-long wine history, while Ukraine started to make good wine only 10–15 years ago, according to local sommelier Anna Eugenia Yanchenko. “Ukrainian wine needs more time to reveal and demonstrate its charms,” she said.

According to Yanchenko, Ukraine can already be proud of two local grape varieties — Odesa’s Black and Telti Kuruk.

“These varieties are the future of Ukrainian winemaking or at least the beginning,” she added.

Another thing that will push Ukrainian winemaking forward is the rise of small businesses, Lacarin said. Compared to big producers that target the average Ukrainian who buys wine in the supermarket, small businesses make more expensive, high-quality wine.

Small producers can take more risks too, experimenting with production techniques, growing grapes without pesticides. For a big winemaker, one mistake can cost dozens of hectares, Shneyderis said.

“It wasn’t supermarkets that made the French wine industry glorious, but small boutiques that produced expensive and classy wine,” he said.