ZHYTOMYR OBLAST, Ukraine – Just on the edge of Vysoke, a village in Zhytomyr Oblast some 150 kilometers northwest of Kyiv, the bumpy oblast road suddenly becomes smooth and well maintained.

And after dark, the streets in this village are not dark or gloomy under weak, yellowy streetlights, as is usual in rural Ukraine, but brightly lit by modern, energy saving lanterns that have light-emitting diodes instead of the usual sodium-vapor lamps.

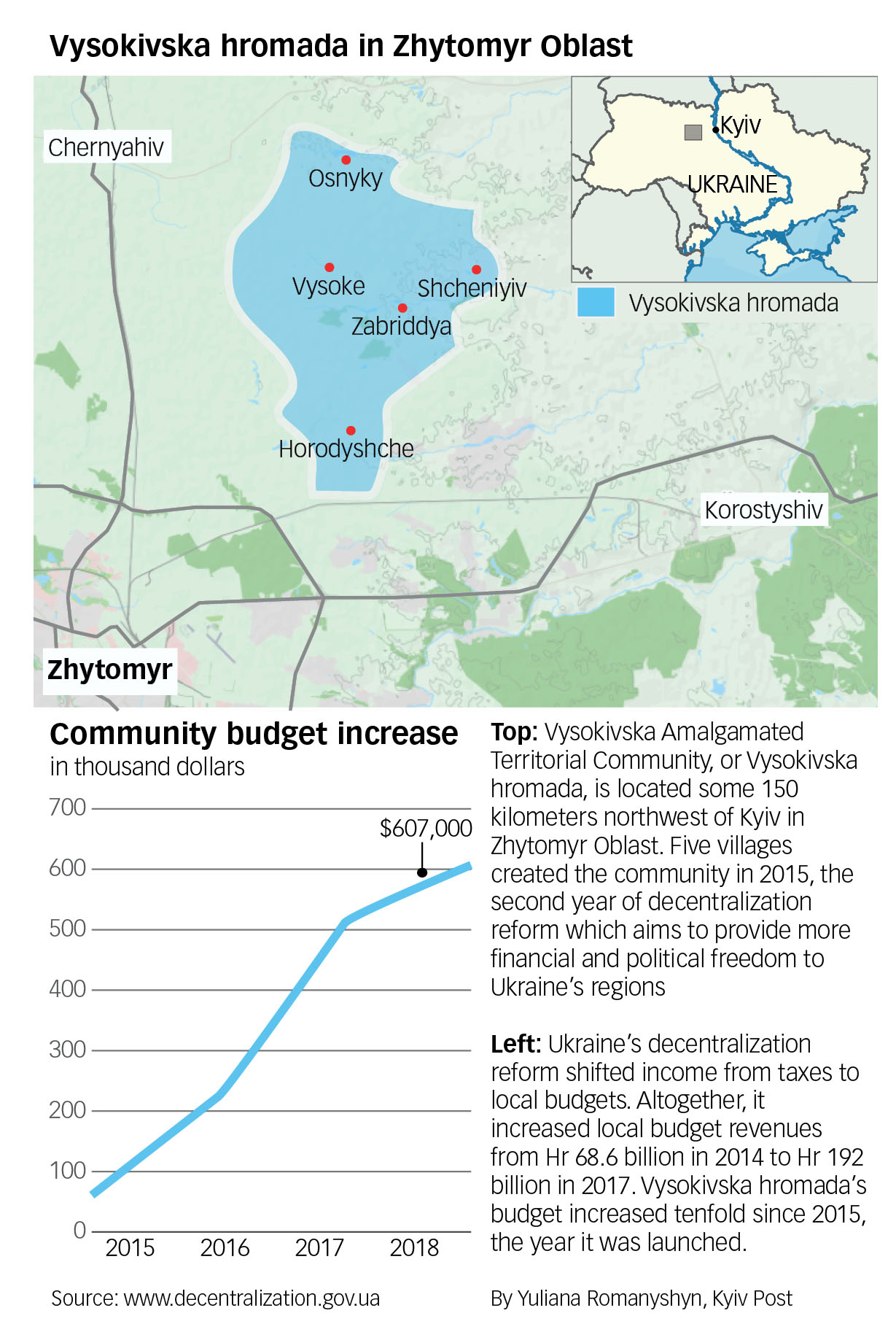

These, and other changes, have all come about in Vysoke since 2015, when the village became the center of the Vysokivska Amalgamated Territorial Community, one of the new local administration units created within Ukraine’s attempt to decentralize power in the country.

The Ukrainian government started decentralization reform in April 2014, giving small villages and towns more economic and political freedom.

Since 2014, more than 3,300 Ukrainian villages and small towns formed 720 larger amalgamated communities, known as hromadas. Now more than 6 million people, or 14 percent of Ukraine’s 42 million population, live in such communities.

The aim is to revive Ukraine’s regions by letting local governments keep most of the taxes they raise from businesses located in the newly created communities, as well as the income tax raised from the people who work locally.

Before, small communities would send the taxes they raised to district, oblast and central government, and then try to claw it back in the form of subsidies, grants and allocations. They weren’t often successful, and village budgets were regularly left empty.

On top of that, village authorities also had few powers. Key decisions on infrastructure repairs, local hospitals and many other issues were administered by district and oblast councils. Decentralization is changing that.

In addition, about 60 percent of taxes remain in hromadas now, while 10 percent goes to the district budget and 30 percent to the oblast budget. Before the reform, it was the opposite: local budgets could keep only 10 percent of taxes.

As a result of the change, local budget revenues around Ukraine went from Hr 68.6 billion in 2014 to Hr 192 billion in 2017.

But decentralization opened other opportunities as well.

Now the united communities, or hromadas, can apply for government loans to develop local infrastructure, healthcare, entertainment and do other community projects. If the loan is spent in time and in accordance with the pre-approved plan, the hromada doesn’t need to repay it.

Still, it is too early to proclaim decentralization a success.

The results of the reform are patchy, Dmytro Klymenko, the spokesperson of Zhytomyr Oblast Local Government Development Center told the Kyiv Post in an interview on May 7.

“Decentralization works but we have seen mixed results from hromadas in different oblasts,” Klymenko said.

While some communities were able to receive the government subventions and use them, as well as local tax money, to repair roads and schools, others turned out less capable. “Some can’t even write a proper business plan, or prefer just to keep the money in the bank instead of spending it,” Klymenko said.

The newly-created community councils are short of skilled staff as many residents leave the region.

“More and more of Zhytomyr Oblast’s residents leave to work in Europe,” Klymenko said, pointing to people lining up at Zhytomyr’s central bus station to take international buses to Poland and the Czech Republic.

Zhytomyr Oblast isn’t alone in that: Almost three million Ukrainians currently work abroad, according to the Center of Economic Strategy, a Kyiv-based think tank, although the number has proven hard to estimate as some work illegally. The whole population of Zhytomyr Oblast is just 1.24 million.

For those who choose to stay and develop their local communities, there are foreign-financed training programs on self-governing.

One of them, U-Lead with Europe, a program co-financed by the European Union and its member states Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Poland and Estonia, trains locals in 24 centers all over Ukraine. The trainees learn how to grow community budget, attract investment, write business plans, and more.

Small but strong

Vysokivska hromada is one of the success stories. It unites five villages in Zhytomyr Oblast – Vysoke, Horodyshche, Osnyky, Zabriddya and Shcheniyiv – that together have 2,600 residents.

The community employs just 13 people who govern it.

In 2016-2017, they managed to raise more than Hr 5 million ($196,000) in taxes and government subventions and got Hr 9 million ($346,000) in grants from international organizations and the Ministry of Regional Development special development fund.

As a result, the community’s budget grew 10 times. In 2015, after this community was created, its yearly budget was just Hr 1.3 million. In 2018, it will raise and spend Hr 15.8 million.

In 2017 alone, Vysokivska hromada installed new street lighting, built a small canteen in a local school, purchased equipment and made repairs in two other schools, reconstructed the village clinic, and even set up an office offering free legal advice for the locals.

“We’ve been using all the possibilities the reform gave us,” Vysokivska hromada head Mykola Barduk told the Kyiv Post.

Barduk isn’t new to local governing. Before the formation of the hromadas, he was the head of village council in Vysoke for more than a decade. He likes his new role much better.

“The money we attract now and the freedoms we’ve been given are incomparable (to the old order),” he said.

Before the decentralization and the creation of the hromada, Vysoke village council got only some Hr 30,000 in government support over 10 years, and received some Hr 1 million a year from the local taxes – in a good year.

“With most of the taxes bypassing our budget, we had to save money for several years to repair one road in the village,” Barduk said.

Two in one

Barduk, a middle-aged man in a suit, looks like a typical Ukrainian official. His cell phone rings every 10 minutes.

With his staff of 13 people, Barduk supervises all of the community’s activities.

Lyudmila Chaika, a woman in her 50s, is his chief accountant. She has worked for the village council for 10 years before transferring to the hromada.

“I can say life has become more interesting and intense for us. Everyone’s doing two jobs instead of one. I like writing project pitches, it’s interesting,” Chaika said.

The hromada’s next project is to demolish an abandoned building in the center of Vysoke, across the road from the local school, and build the second health clinic on the site.

One of the local mining companies provided a bulldozer and trucks for the demolition for free, and locals helped with the work.

Next on Vysokivska Community’s list is building a kindergarten, setting up WiFi at bus stops, installing security cameras, creating two police departments, finishing the school stadium construction, and repairing more roads.

Business helps

The main thing contributing to the financial success of the community is local business.

The five villages of Vysokivska hromada are doing well comparing to many other in Ukraine: An agricultural holding Agrostem, two farms, and three mining companies provide jobs. Each employs about 60 people.

The average monthly salary here is Hr 7,000, while some positions, like a tractor driver, can earn up to Hr 18,000.

More businesses are to come: Barduk says that an unnamed investor is about to start another labradorite mining company here. The mineral is used in road surfacing and construction and is exported to Italy, China and India.

Both Barduk and Klymenko said that after the creation of hromadas, more local businesses are willing to employ people legally and pay taxes – they like that 60 percent of the tax money now stays in the community.

Also, the businesses can substitute part of the tax payments with services to the community or sponsorship of local events. One of them is the annual electronic music festival Pulse Fest that will welcome more than 1,000 guests on June 21.

“We believe that it is possible to revive Ukraine’s villages,” said Larysa Barduk, the principal of the local school and the wife of the hromada head, adding that decentralization is the way to do it.

“If you know you’re working for yourself it motivates you like nothing else.”