For most Ukrainians, economic life is still hard.

But for Engin Akcakoca, head of PrivatBank’s supervisory board and a longtime agitator for reform of Ukraine’s financial sector, there’s a clear solution to improve prosperity.

“This government’s adherence to fiscal discipline, which will be supported by the application of prudent monetary policy by the (National Bank of Ukraine), coupled with the renewal of cooperation with the (International Monetary Fund), will definitely result in a stronger Ukraine and happier Ukrainian citizens,” he told the Kyiv Post.

These days, the 67-year-old Akcakoca is mostly occupied with bringing PrivatBank into fiscal health before 2022, when the lender is set to be privatized.

But broader concerns over a spate of unpassed legislation meant to fortify creditor’s rights and redesign the oversight of state-owned banks has him worried.

“Every amendment to the laws that were aiming to improve the rights of the creditors to improve were never finalized properly,” he said. “If the creditors are not protected adequately, lending will not start in Ukraine.

Maybe this is a very significant comment, but in simple terms it is this: If I, as the lender, am not sure what is going to happen to my mortgage, I will not lend.”

PrivatBank risks

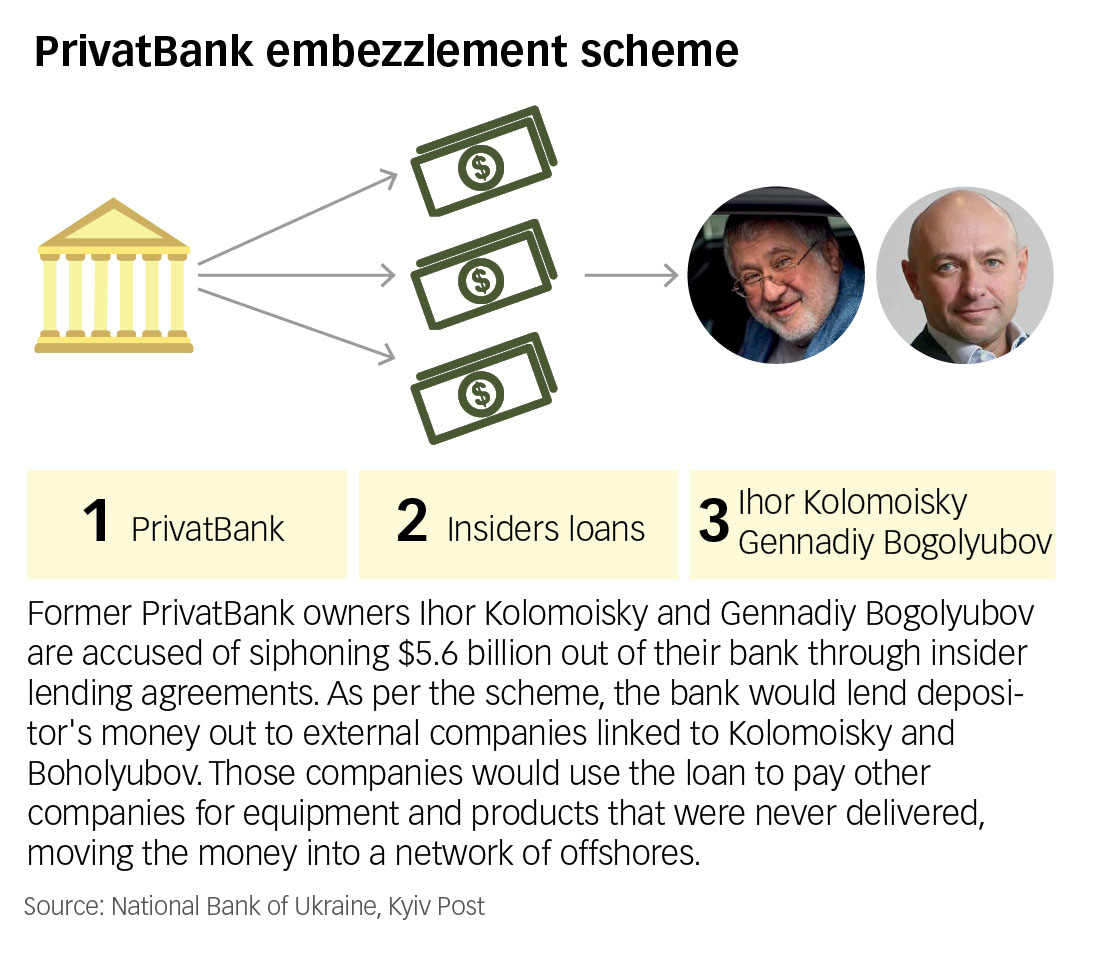

PrivatBank’s nationalization has sparked a battle to return $5.6 billion that was stolen from the lender’s coffers, allegedly by its former owners, Ihor Kolomoisky and Gennadiy Bogolyubov.

The bank has filed a $2.5 billion lawsuit in London, as well as smaller cases in Ukraine and Switzerland. The lender also sued Big Four auditor PwC in Cyprus, accusing it of misappraising collateral used to secure insider loan agreements by which the cash was allegedly extracted.

Immediately after the nationalization, Privat engaged Kolomoisky in negotiations to collateralize some of the related-party lending agreements through Rothschild & Co., the international financial advisory group.

Those talks fell apart within months.

“There was no common understanding between the two parties,” he said, before adding that the bank “is trying to do its best to recoup the losses that the bank previously incurred.”

Other risks face the bank.

A lawsuit from PrivatBank eurobond holders that were bailed in during the nationalization have filed an arbitration lawsuit in London, which could cost the bank up to Hr 15 billion ($532 million) in the event of a loss. Akcakoca declined to comment on that issue.

But yet another challenge is that of Privat24. As the country’s most-advanced online banking system, it continues to process a plurality of payments in Ukraine.

But the platform — though a big advantage to the bank — faces crucial issues in that certain software on which it relies belong to outside organizations, creating vulnerabilities given alleged ties between those owners and the bank’s former management.

Akcakoca said that the bank intends to develop its own software to replace the systems, conceding that that may cause “court cases in the future.”

“Look, if you have any software that you borrow or rent, or you bought from third parties that you may have difficulty maintaining in the future, you have to develop your own at some point,” he said. “You have to develop your own architecture.”

Privat plan

The lodestar of PrivatBank’s future is a strategy for the bank, approved by the Cabinet of Ministers in April. The plan envisions the bank being sold by 2022 to a private investor.

Akcakoca emphasized that he made “no segregation” between a potential foreign or Ukrainian investor.

The essence of the plan is to pump up the bank’s retail banking component by increasing lending and expanding Privat’s infrastructure around the country.

For example, the bank plans to raise the number of ATMs it has around Ukraine to 200,000 from its current number of 166,000.

Lending presents the trickiest part of the plan. The same problems around corruption, rule of law, and accounting standards that prevent foreign investment in Ukraine also curtail widespread lending.

At the same time, opening up PrivatBank’s loan portfolio to the Ukrainian economy could provide a real boon to the country’s businesses. The $5.6 billion stolen by the former owners was siphoned out through insider lending agreements; unleashing that capital to productive industry could be a game-changer for Ukraine.

Akcakoca said that he believes that large loans to huge corporate clients are more likely to go bad than those to small and medium-sized businesses.

“For a banker, it’s easier to extend a wholesale loan, a big ticket item, but it’s easier for it to become a bad asset,” he said. “So we decided to be selective in corporate banking.”

“Corporate for us is big ticket items,” Akcakoca said. “As long as it’s in line with our rules and procedures and understanding of risk management and as long as it provides synergy to the bank, we will be in it.”

He added that while the agricultural and metallurgical sectors in Ukraine are the most interesting, foreign-owned companies would likely hold the most promise for future loan agreements.

“In developing countries, when you talk about this kind of a strategy for corporate banking, naturally foreign companies rank number in your target market,” he said. “That does not exclude the Ukrainian companies as long as they fall into the conditions.”

Though the 2022 plan will dictate PrivatBank’s development until then, Akcakoca said he would be open to an offer from a suitable investor.

“Today’s cash is more valuable than tomorrow’s cash,” he said.

At the same time, state ownership presents peculiar issues for the longtime private lender. In many countries, state-owned banks make loans that benefit the public interest, but may not necessarily be profitable on the open market.

Akcakoca said that there had been “no pressure” to undertake directed lending.

”And I am very happy of that because we have a common understanding with the major shareholder that if we have state risk in the bank it may make it difficult to privatize it by the end of 2022,” he said.

Another risk is that of the 2019 presidential election. With the bank’s former shareholder said to be backing the Ukrainian opposition, many observers have come to see PrivatBank as a potential bargaining chip, depending on the election outcome.

But when asked what role the presidential election would play in the bank’s future, Akcakoca demurred.

“Sorry, I don’t understand English,” he joked in lieu of a “no comment.”

Emissary of the Western backers

A native of Turkey, Akcakoca has decades of experience in the financial sectors of emerging markets.

Before joining PrivatBank, he worked as an advisor to the IMF. He helped develop a package of legislation to revamp Ukraine’s financial sector, elements of which are currently slouching through the Rada.

The main piece is a bill intended to further strengthen creditor’s rights, partly by improving collateral requirements and removing obstacles to legal settlements.

Another piece of legislation aims to revamp the management of Ukraine’s state-owned banks. Backed by the IMF, the bill introduces changes to the lenders’ boards of directors that makes them more independent, and attempts to bring their corporate governance in line with international standards.

It’s an important move: since the December 2016 nationalization of PrivatBank, state-owned banks in Ukraine have come to account for more than half of the country’s market share.

The Rada passed the bill on July 5. Poroshenko has not yet signed it into law.

Saying that the changes were “pending the president’s signature,” Akcakoca added: “And I hope that signature will be obtained as soon as possible.”