The collapse of one of the largest construction firms, two elections and the coronavirus pandemic could have destroyed Ukraine’s real estate market in 2019–2020.

Instead, both commercial and residential real estate in Ukraine have been growing, albeit slowly.

“The absence of a decline could be counted as growth for real estate in Ukraine,” says Igor Nikonov, founder of construction firm KAN Development. “The number of sales was stable, prices were stable too, the economy was growing. A sin to complain.”

Over the last year, property has remained the most stable investment for Ukrainians, while foreigners kept putting their money into local real estate due to fast returns. Retail and residential property, meanwhile, flourished on stability and purchasing power slightly rising.

It’s one of the surprises during Ukraine’s quarantine to prevent the spread of COVID-19: real estate has remained strong, outperforming expert predictions.

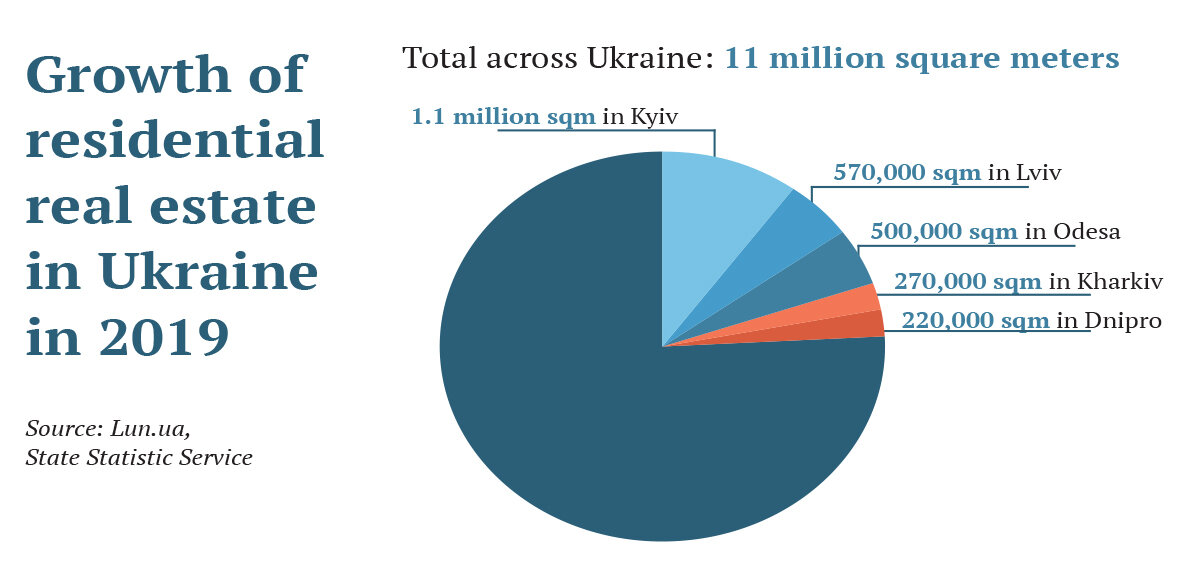

An aerial view of a residential complex called Comfort Town in Kyiv. Ukrainian construction companies managed to build 11 million square meters of residential property in 2019, nearly 3 million square meters of which were built in Kyiv and Kyiv Oblast. (Shutterstock)

Office market

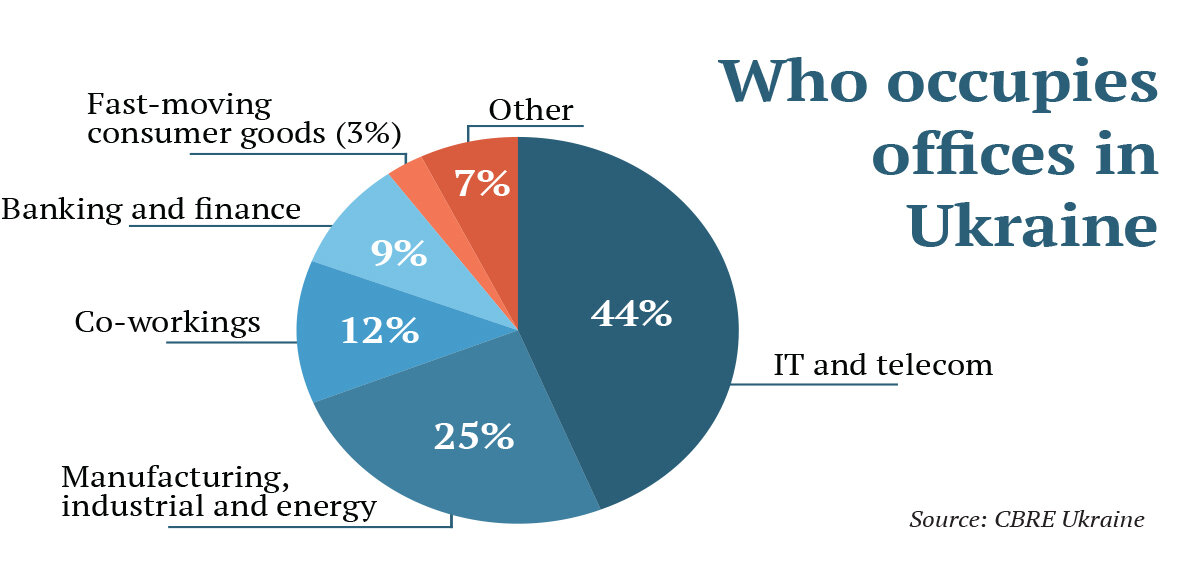

Despite political instability due to presidential and parliamentary elections in 2019, the macroeconomic situation in Ukraine improved. This, according to real estate analyst CBRE Ukraine, increased annual take-up of offices in Kyiv by 17%, or 170,000 square meters of leasable office space.

The biggest drivers for growth in this real estate subsector are the high-tech and telecom industries, which rent 44% of all the offices in Ukraine. In 2019, for example, it was tech companies SoftServe and EPAM who started renting the biggest offices — 12,700 and 7,100 square meters respectively.

Additionally, most tech specialists in Ukraine are contractors—out of an estimated 200,000 techies, 180,000 are individual entrepreneurs, according to government data. This means that most of them don’t have an office and either work from home or rent a place. This factor has stimulated demand for and supply of coworking spaces, which today represent 12% of the total take-up on the office property market.

In general, new office space almost doubled in 2019 compared to 2018 and amounted to 100,000 square meters, with Sigma, Wave Tower and UNIT.City B10 among the major constructions. These three spaces now offer nearly 45,000 square meters of leasable area.

Nevertheless, according to Sergiy Sergiyenko, managing partner at CBRE Ukraine, the new construction still couldn’t meet the existing demand. There is more room for growth.

According to public data, Kyiv developers plan to construct about 255,000 square meters of office space by the end of 2020.

Source: CBRE Ukraine

Annual investment volume in Kyiv declined to $73 million in 2019 compared to $130 million in 2018. The two key transactions were made by furniture company Merx Group: It acquired the office building of the former Khreshchatyk Bank for $17 million and business center Incom for $15 million.

One of the biggest local investors in real estate, Dragon Capital, bought three small office buildings in Kyiv with a total area of 13,000 square meters, increasing the number of office buildings in its real estate portfolio to 11.

Once the coronavirus pandemic reached Ukraine in March 2020, the work of the whole office sector changed— only 30% of Ukrainians continued to work in office settings like they did before the pandemic, according to various estimates.

Sergiyenko from CBRE Ukraine, however, thinks the changes are short-term, because people can’t keep working remotely. “People have always worked together,” he says. “And it’s just impossible to work together when you are not together (physically).”

Once a vaccine against COVID-19 is developed, Sergiyenko thinks, people will return to offices and the market will return to normalcy.

Developers and real estate investors aren’t planning new construction before a vaccine is out, but those who began constructing new offices before the pandemic сontinue to do so, as it is often more expensive to stop the process, experts say.

Retail

Kyiv real wages — income expressed in terms of purchasing power as opposed to actual money received — saw an 8.4% increase last year, the first significant growth since 2016. Prices, in turn, grew more slowly in 2019, by 3.9%, compared to 8.8% in 2018.

These changes — although slight — were enough to boost consumption and create more demand for Kyiv retail property, according to CBRE estimates. In particular, increased purchasing power has contributed to further expansion of supermarket chains: Billa, Novus and Silpo collectively opened 21 new stores in the capital alone.

Fashion brands, meanwhile, remained leading players in the structure of new retail entries (36%), with 11 international brands opening in Ukraine in 2019 (down from 20 in 2018). Among the newcomers are clothing brands Supreme Spain, The North Face and Decathlon.

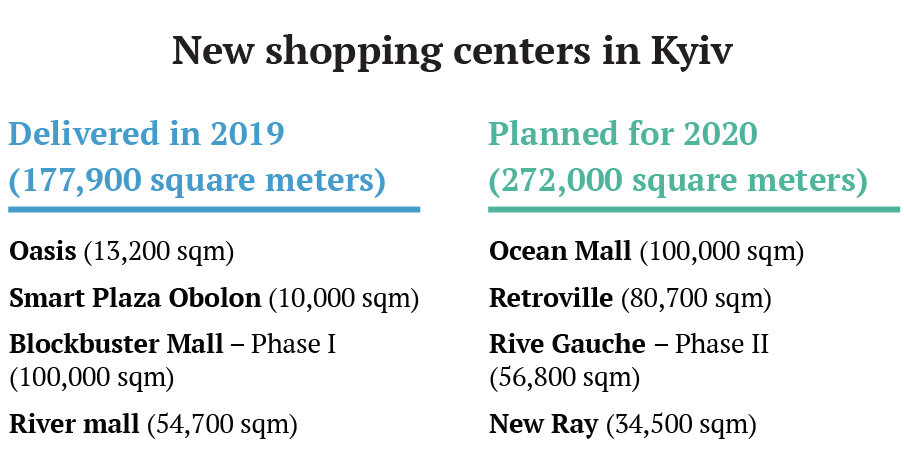

The total annual volume of new developments for retail amounted to 178,000 square meters, three times as much as in 2018. As of the beginning of 2020, the total leasable area for retail in Kyiv has been 1.3 million square meters, according to CBRE estimates.

At the same time, foreign investment into retail real estate in Ukraine dropped to $85 million in 2019 compared to $98 million in 2018. But the office and warehouse subsectors received less last year, $73 million and $61 million respectively.

Provided that purchasing power continues to grow and quality malls open, more premier international brands may enter the market, following the latest long-awaited entry of Swedish clothing company H&M in 2018. During 2020–2021, more than 20 new cross-border retail chains are expected to enter Kyiv, including furniture company IKEA, which has just recently opened an online store in Ukraine.

In the long-term perspective, shopping centers aren’t expected to close, according to CBRE. But given that many retailers were forced to develop electronic commerce — websites, delivery, etc.— malls may transform, giving more space to entertainment and less to commerce.

“Over time, we will have not just shopping malls, but places of socialization, leisure and trade, where trade itself will still be predominant, but not determining the preferences of visitors,” says Stanislav Ivanov, assessment and consultancy department head at CBRE. Some malls may also introduce coworking spaces, Ivanov thinks.

What’s already changed today is more frequent cleaning, disinfection tools, temperature checks, medical masks and control over the amount of visitors.

Residential

In 2019, one of the largest Ukrainian property developers, Urkbud Development, collapsed. It failed to finish 25 residential complexes, leaving 13,000 backers without apartments.

Despite that, other local firms still managed to deliver 11 million square meters of residential property last year, nearly 3 million square meters of which were build in Kyiv and Kyiv Oblast.

The average price of a square meter in these new buildings is $940, while the minimum is $660, according to Lun.ua, an online marketplace for real estate. Meanwhile, to rent a one-room apartment in central Kyiv, one will have to pay at least $450 a month.

People kept buying residential property because, in Ukraine, there’s simply no other investment opportunities as good as buying an apartment, according to Natalia Romanyuk, CEO of NR Property.

“Other investment means are too risky,” says Romanyuk, who’s been in the business for 20 years. “Real estate remains the number-one investment to preserve money or even to profit in the future.”

Nevertheless, the deficit of residential real estate remains high in Ukraine, according to her. The main constraint is high mortgage rates (18–22% per annum), which means that fewer people can afford to invest in new housing complexes and so fewer developers have enough backers to start constructing.

The construction of a residential complex takes 2 years on average and, once it’s finished, apartments get 20–25% more expensive.

A man walks in Kyiv on April 24, 2020. Kyiv residential complexes, like the one in the background on this photo, on average sell for

$940 per quare meter. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Meanwhile, demand grows and will do so for a long time, because there isn’t enough residential real estate in the country. In Ukraine, every person has about 20 square meters of living space, while, in Europe, it’s over 40, according to estimates by construction firm Kyivmiskbud.

Foreign investment in Ukraine’s apartments flows mosty from Israel and the United States, according to Romanyuk. For these countries, it’s an attractive investment opportunity because of fast returns: it takes up to 10 years for a residential property to significantly grow in price as opposed to 20 years in Israel and 15 in the U.S.

During the quarantine, the market for residential real estate has slowed down. Some developers even stopped building simply because people self isolated and stopped buying property, according to KAN Development.

The prices, nevertheless, haven’t dropped during the quarantine and the cost of construction has even risen because developers started to spend more money on security at construction sites.

Romanyuk says people predicted that the market would sink by 50%, but it hasn’t happened. Today prices for real estate that is still being built or is recently completed have gone down only by some 10%.

Romanyuk says that trying to predict the effect the coronavirus pandemic will have on the real estate market is like “fortune telling with coffee grounds.”

She’s sure that people will always want “to see their investment in real life,” so unless the restrictions are eased, there inevitably will be fewer buys.