Ukraine’s coal industry has been dying for years. Now, as the government slashes subsidies and moves to close unprofitable mines, miners are taking a stand and demanding more state support.

In Soviet times, the Donbas was a center for coal mining and metallurgy. However, the industry has been in steep decline due to corruption, economic crisis, inefficiency and, most recently, Russia’s war against eastern Ukraine. Today, the Ukrainian government operates 35 mines, most in Lviv and Volyn oblasts, along with several other mines in Ukraine-controlled parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

The coal industry in Ukraine has always been heavily subsidized by the government. For instance, in 2013 it received nearly Hr 13 billion ($520,000). But after Russia’s war, the subsidies dropped sharply.

In addition, as a stipulation of the International Monetary Fund’s loan program in 2015, Ukraine pledged to reduce subsidies to state-owned enterprises, including those in the coal industry. The Ministry of Finance has earmarked Hr 1.8 billion ($72 million) for coal mining in 2017.

But this money won’t even cover salaries to miners, let alone the maintenance of mines, said Mykhailo Volynets, the head of the Independent Trade Union of Miners of Ukraine . The union demands that state support be increased to Hr 4.6 billion ($184 million).

Furthermore, according to the state program for reforms in coal industry until 2020, the government intends to lay off 20 percent of the mine’s workforce, or nearly 10,000 people. It plans to continue supporting only a third of the state-owned mines and either privatize or close the rest. Next year, almost a half of the state funds allocated to the coal industry – Hr 800 million ($32 million) – will be spent on closing down unprofitable mines.

“The government suggests reducing the sector by closing down mines and leaving thousands of miners jobless, instead of trying to develop the infrastructure. We don’t see any future for the coal industry in Ukraine,” Volynets told the Kyiv Post.

Mykhailo Volynets, head of Independent Trade Union of Miners of Ukraine. (Courtesy)

In contrast, the Ministry of Energy and the Coal Industry is convinced that the reforms will be good for one of the most corrupt parts of the energy sector.

Roman Nitsovych, a program manager at Dixi Group, a Kyiv-based think tank that focuses on research and consulting in the energy sphere, said that he understands why the government wants to get out of the coal business, and leave it to private investors.

“In a competitive business environment it is economically unviable to continue subsidizing state-owned mines,” said Nitsovych. “How the government carries out the restructuring is another question,” he said, adding that the premises of closed mines could be used by other industries.

With the gloomy prospect of redundancy hanging over them, miners at state-owned mines have been fighting to be paid three months’ worth of pay owed to them by the government. On Nov. 7, 50 workers from the No. 10 Novovolynska mine in Volyn Oblast went on hunger strike, demanding not only unpaid salaries, but also funding to finish construction work at the mine. About 10 days before the start of the hunger strike, 300 people from the same mine blocked the Yahodyn checkpoint on the border with Poland.

“We have been fed promises,” complained one of the miners, Oleksandr Herasymchuk, who spent the last 10 years working in the Novovolynska mine and has been waiting to be paid since September. “We went to Kyiv twice to meet with Verkhovna Rada (lawmakers) and the Ministry of Energy – to no avail.”

Amid the growing discontent, Minister of Energy and the Coal Industry Ihor Nasalyk visited state-owned mines in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts on Nov. 15-16. He stated that all salary debts would be paid off by January.

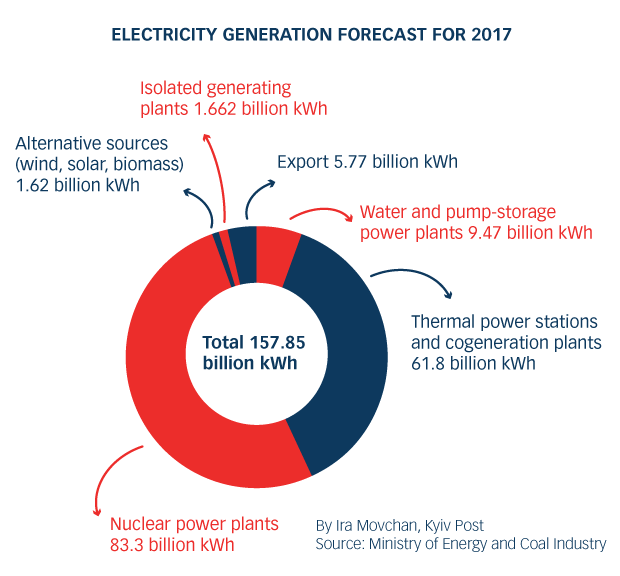

Ukraine relies heavily on coal-generated energy.

Price dispute

Since the government is determined to cut subsidies to the coal industry, the miners believe that a fairer price policy in line with world prices could positively affect the situation and save the mines.

In March the National Commission for Energy, Housing and Utilities Services Regulation introduced the Rotterdam Plus formula to set the wholesale market price for coal, which led to the increase in electricity tariffs in May. The formula takes as a basis the price of coal in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp ports, and adds to it the cost of shipping the coal to Ukraine. At the moment, one ton of imported coal costs around Hr 2,300-2,400 ($92-96), while domestically extracted coal sells for around Hr 1,390 ($56) per ton.

“We pay for gas and electricity at international market prices, so why can’t Ukrainian coal cost as much as imported coal?” asked miners’ union leader Volynets. “Our government even buys coal from an aggressor country, Russia, for $90.”

Nitsovych said that the Rotterdam Plus formula allows power stations to make a profit, but not coal producers, since the prices of coal are set by the Energy Ministry. This being so, the main beneficiary has been DTEK, the largest private power generating company in Ukraine, owned by the oligarch Rinat Akhmetov. DTEK controls 70 percent of Ukraine’s power generation capacities.

In addition, the use of the formula obscures the important difference between brown coal and anthracite coal. They are not interchangeable and should be priced separately. The latter is imported from the occupied territories of Ukraine, but is formally documented as being Russian coal, according to the trade unions.

The controversial formula has come under fire from members of the Ukrainian parliament and the expert community. In September, a former member of the National Commission for Energy, Housing and Utilities Services Regulation, Andriy Gerus, filed a lawsuit to declare the formula illegal.

According to Ministry for Energy and Coal Industry statistics, this year Ukraine has already imported 12.1 million tons of coal at a total cost $1.2 billion. Most of it came from Russia, the United States, Australia, Poland and South Africa.

At the same time, state-owned coal mines decreased production by 13.8 percent in 2016, to only 774,000 tons of coal.