State-owned natural gas explorer Ukrgazvydobuvannya, known simply as UGV, thinks it can make Ukraine independent in this vital source of energy that powers industry, business and homes.

“Ukraine is clearly missing the opportunities,” said CEO Oleg Prokhorenko. “But we have a plan to make Ukraine gas independent.”

The company expects to turn itself around this year, achieving increased growth of gas production in 2017, for the first time since Ukraine achieved independence in 1991.

The plan is for domestic production and consumption to meet eventually, one of these years.

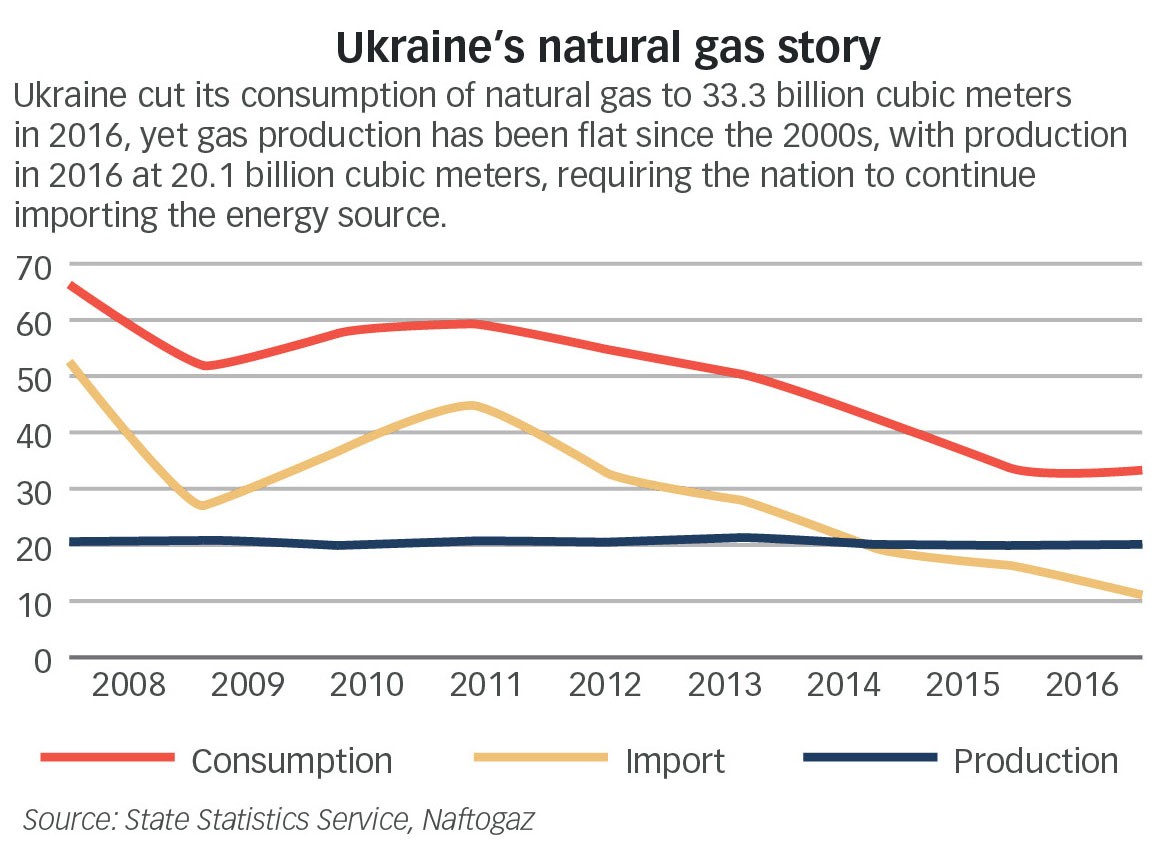

However, there’s still a big gap: Ukraine produces 20 billion cubic meters of gas and, only by 2020, consumption is hoped to decline to 26 billion cubic meters from 33 billion cubic meters.

The additional 6 billion cubic meters is expected to come from private producers and UkrNafta, the oil-producing Naftogaz subsidiary.

The ambitious plan relies on Ukrainians conserving more because of higher, market-based heating prices, but also on Prokhorenko successfully refurbishing the company’s drilling fleet and reorienting it to hydrofracking — an innovative technology that is beginning to unlock previously untapped gas reserves across Ukraine, as it has around the world, boosting supplies of natural gas worldwide.

The company has been a beneficiary of the government’s International Monetary Fund-backed policy of increasing gas prices on household customers, giving the company more money to invest.

“I spoke to my mother, and she said that when it’s about 22 degrees Celsius, I start to feel hot.

That’s what Europe lives through. People have responded to higher prices” by conserving energy, Prokhorenko said. At subsidized prices to consumers, “it was very difficult to invest in new assets,” he said.

Ukrainian gas heritage

Ukraine was the Soviet Union’s original gas hub. In the 1950s, as the Soviet economy sought to expand after its post-war rebuilding, Moscow seized upon vast gas reserves in the eastern regions of modern Ukraine. Soviet engineers, trained in Kharkiv, developed fields in Poltava and Kharkiv oblasts, with the Shebelinka field in Kharkiv Oblast, founded in 1956.

According to one report, more than 1 trillion cubic meters of gas were extracted from the field between 1956 and 2006, averaging 20 billion cubic meters each year. Ukraine consumed 33 billion cubic meters in 2016.

The Ukrainian boom stopped in the 1970s, when massive gas reserves were discovered in Siberia. As the Soviets pulled out of Ukraine, gas production fell to around 20 billion cubic meters each year, about where it remains today.

Investing for future

When Prokhorenko arrived at Ukrgazvydobuvannya, the company was reeling from corruption scandals.

One involved former People’s Deputy Oleksandr Onyshchenko, who fled the country last year amid accusations that he stole $110 million from the company. The same scandal later brought down former Fiscal Service Chief Roman Nasirov, who allegedly allowed participants in the scheme to delay tax payments in exchange for a kickback.

But Prokhorenko ignores the past, and has focused his efforts on refurbishing the company’s rusting Soviet equipment. He said that the cost to repair a single drilling rig was “relatively low,” ranging from $200,000 to $1.5 million, depending on the “complexity of the repair.”

The plan is to invest in hydraulic fracturing on a large scale.

Hydraulic fracturing, also known as hydrofracking, is a way of extracting natural gas by using fluids to break apart rock formations in which the gas is trapped.

“This company had its own hydrofracking fleet, but it was outdated,” he said, and in disuse. “For us, this was a strategic priority. We basically said, look. If we want to increase production quickly, we should start hydrofracking.”

UGV statistics suggest that the company is on target to improve production in 2017, in part because of 100 hydrofracking operations in use now.

Prokhorenko said that he has negotiated fixed-price contracts with foreign companies to help with hydrofracking and coil tubing operations.

Not all rosy

The global popularity of fracking technology — and its ability to tap new gas reserves at attractive prices — is viewed as a threat by the Kremlin to Russian state-controlled Gazprom’s dominant position in natural gas production. Prokhorenko said Russian interests are behind local opposition to fracking.

Moreover, suspicions and speculation are rampant about UGV’s ties to billionaire oligarch Victor Pinchuk.

UGV chief operating officer Alexander Romanyuk worked at Pinchuk’s EastOne until he joined UGV, while Alexander Klimov worked as head of investments for UGV after spending five years at EastOne and another five at GeoAlliance, a Pinchuk oil venture.

Between August 2016 and June 2017, at least Hr 2.15 billion ($80 million) in steel pipe purchase tenders for UGV went to Interpipe.

Volodymyr Gaidash, UGV’s communications chief, argued that there was nothing untoward in the relationship and affirmed that nobody in UGV would stand to gain from Interpipe’s purchases.

“These are frequent allegations, spread by our competitors,” he said. “We are trying to widen our scope of suppliers.”

“Oleg is graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government,” he said, defending Prokhorenko’s qualifications. “Romanyuk is easy target,” Gaidash said, because he is responsible for making production decisions, creating spurned competitors.

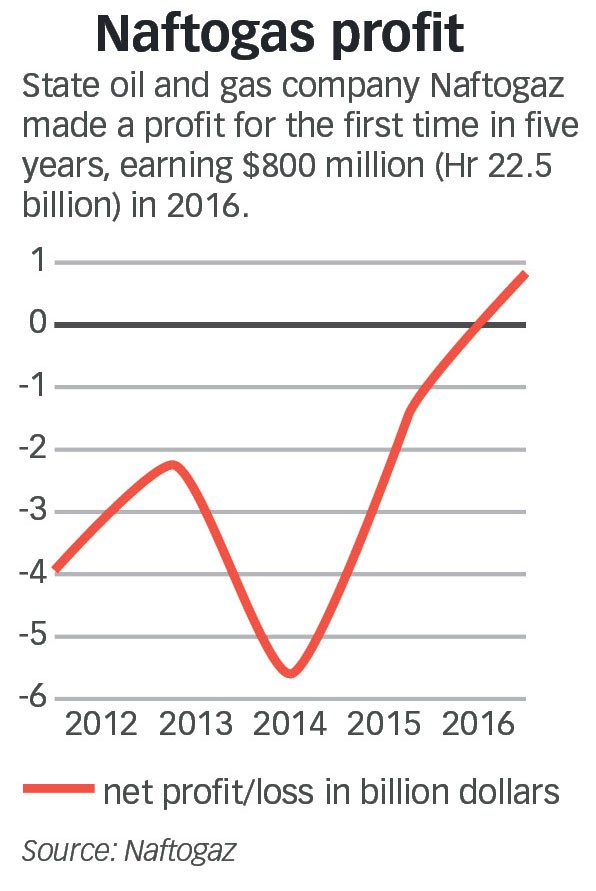

The firm has been profitable for the Ukrainian government under Prokhorenko’s management. Last year, it supplied half of the Hr 12 billion (now $446 million) dividend that Naftogaz delivered to the state budget.