As the Ukrainian state increases the tax burden on small businesses, multinational corporations continue to minimize or evade taxes using a smart and complicated loophole: transfer pricing.

Transfer pricing is when different units of the same international company to trade with itself across borders. But the practice is open to abuse. In some cases, multinational companies rig the internal pricing of their own goods to shift profits around the world into tax havens.

A company with operations in Ukraine, for example, can sell its goods at a low rate to a related offshore firm in Panama. The Panama offshore can then sell the same goods to the destination country at a high price, shifting the multinational’s profits away from Ukraine and to the offshore tax haven.

The Ukrainian government only started paying attention to the issue in October 2013, passing a law that asserted regulatory control over the practice.

Before that, according to an estimate from a Ukrainian newspaper Dzerkalo Tyzhnya, the country’s budget lost up to $22 billion, or about 12 percent of its gross domestic product, every year due to transfer pricing.

And there is no reliable estimate of how much Ukraine is still losing through this tax loophole.

Nuts and bolts

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development estimates that 60 percent of world trade occurs between related parties, in the form of so-called “intra-firm trade.”

The International Monetary Fund estimated in one study that the annual global loss of tax revenues from transfer pricing stands at $600 billion.

Alex Cobham, chief executive of the Tax Justice Network, said that tax havens like Luxembourg, Bermuda, Ireland, Panama, and Singapore gain from the practice at the expense of countries in which the economic activity is actually taking place.

“Most countries are losing, and some are losing very heavily as a proportion of their GDP,” Cobham said. “There are only a few that are systematically winning.”

In Ukraine

Ukraine’s tax authorities are relatively inexperienced with transfer pricing, people who work in the field said.

National Bank of Ukraine Governor Valeria Gontareva alluded to the issue in a June interview with Ukrainska Pravda, calling it a “big problem.”

Gontareva said that while the economic crisis had led to “tight profit margins,” which thereby reduce transfer-pricing abuses, the problem would likely worsen again once margins begin to grow.

The Ukrainian government regulates transfer pricing by asserting its right to review certain kinds of transactions. Regulation of the area is new for Ukraine – the threshold for reviewing transactions was set only in early 2015.

Back then, the threshold was set for companies that make more than Hr 50 million ($1.8 million).

At the start of this year, the government tripled the threshold to Hr 150 million ($5.5 million).

According to Konstantin Karpushin, the head of KPMG-Ukraine’s transfer pricing group, the change will likely reduce pressure on smaller companies with smaller margins. The effective increase is diluted by the fact that the hryvnia has lost 22 percent of its value since 2015.

Karpushin said that both the World Bank and the IMF have been pushing for the threshold to be totally removed.

“It’s additional power in the hands of the tax authorities, and they can use it in the wrong way,” Karpushin added.

Transparency

The absence of transparency makes it difficult to see who is abusing transfer pricing and who is honestly trading goods around multinational business empires.

The OECD sets an “arm’s length” standard for deals between related businesses, which mandates that companies treat related party trades with the same market-based valuation approach that companies use when selling to unrelated suppliers.

But a lack of information plagues Ukrainian companies in this area, making it harder for them to determine what market rates really are.

Sofiya Svystun, a senior tax consultant at the Kyiv branch of Baker Tilly, said that there was no unified Ukrainian database showing profitability rates and financial information among Ukrainian companies, making it difficult to get accurate estimates of real market rates, or tell who might be abusing the system. Svystun added that the information would not fall under Ukrainian trade secrets law.

“Why does this information appear in foreign databases, but there’s no such open resource in Ukraine?” asked Tatiana Stretovych, head of Baker Tilly’s tax and legal department in Kyiv.

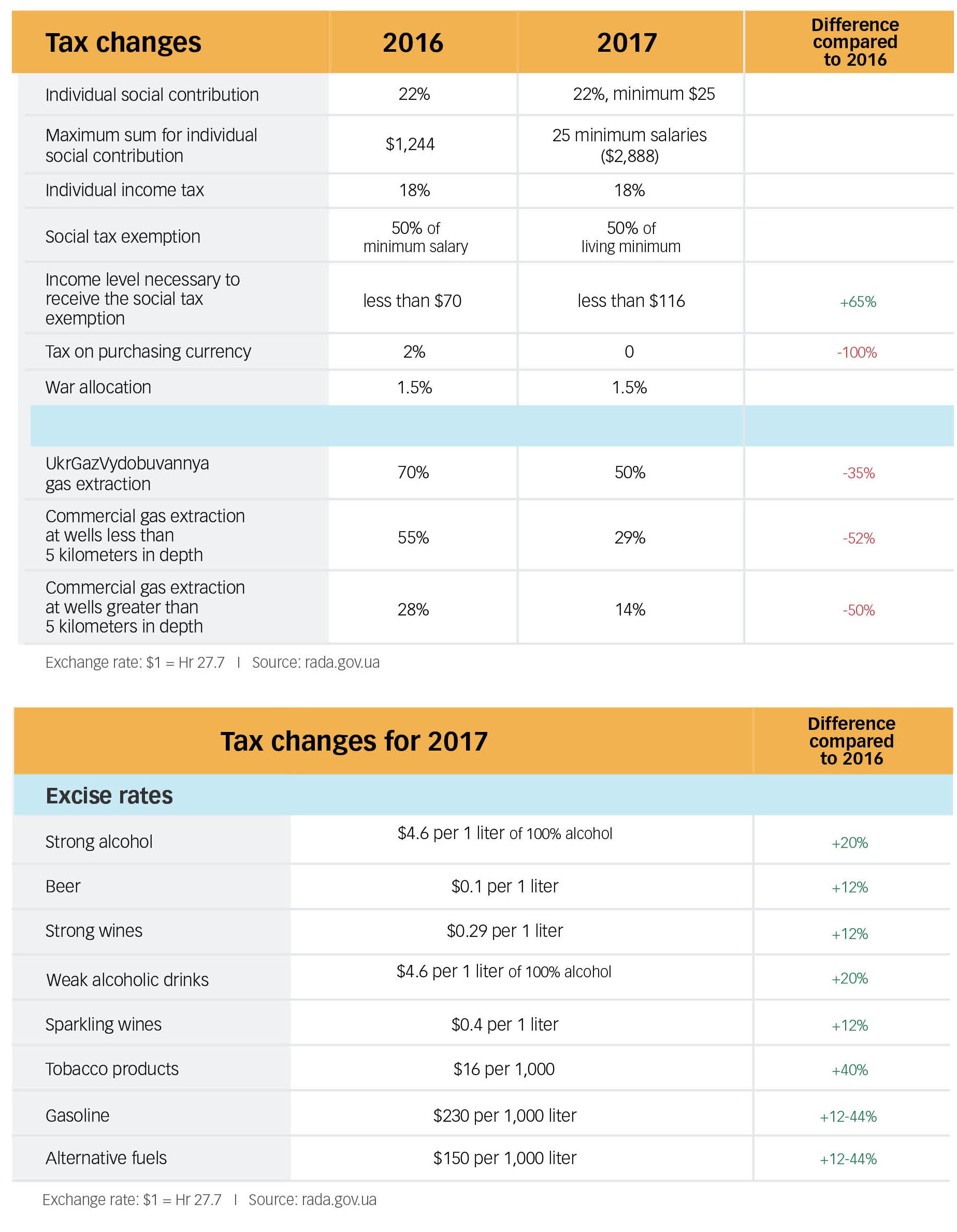

Parliament is moving to adjust tax rates in key areas of the economy.

Big four

Cobham, the tax activist, said that more companies are providing local tax services with “country-by-country” reporting, showing profitability rates for each nation in which they operate. These reports, though not usually released to the public, make it easier to crack down on tax evasion through transfer pricing.

But the auditors, while insisting on maintaining high compliance standards, may be part of the problem, Cobham said.

The firms, which count transfer pricing as a key part of their business, emphasize that they maintain strict compliance standards. KPMG’s representatives laughed off the suggestion that they would use transfer pricing to reduce effective tax rates, saying that their clients were often publicly traded multinationals that would not risk their reputation on compliance missteps.

But Cobham said that when companies hire a Big Four accounting firm, “they on average will see a growth in the number of tax haven subsidiaries they have, and they will see those being used more.”

“This doesn’t happen in a bubble,” he added.