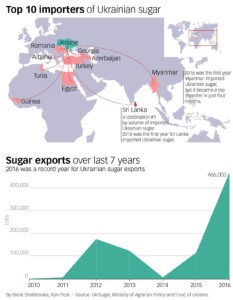

Ukrainian sugar producers had a very sweet 2016, with record exports.

Shipments totaled 466,000 tons, with exporters breaking into new markets, including Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Macedonia, China and others. Exports have risen as production increased in Ukraine, while domestic consumption has remained level.

The industry has also seen foreign investment. In December, a German company with a century-long history in the sugar business bought another six sugar plants in western Ukraine, bringing to eight the number it owns in the country.

But the industry remains irked by the small duty-free EU quotas introduced when Ukraine’s free trade agreement with the EU came into effect in 2016. Those quotas prompted exporters to search for new opportunities in the Asian market.

Export expansion

Still, the EU trade agreement, the hryvnia’s abrupt devaluation and large stocks helped boost the record exports.

Poor harvests in Brazil and India, decent prices on the international markets and the growth of beet production in Ukraine also helped.

“Ukraine is continuing to increase its export potential and is confirming its world leadership,” Ukrainian Agriculture Minister Taras Kutovyi said on Jan. 12, referring to the record sugar and wheat exports.

The nation’s top sugar producer, Astarta Holding, which specializes in processing beets into sugar, was also last year’s top exporter. Operating eight plants, the company increased production for export to 186,000 tons – 40 percent of the country’s entire sugar exports.

Mykola Kovalskiy, chief strategy officer at Astarta, said a combination of quality, price, and a decrease in gas consumption has made the company more competitive.

Ukrainian sugar producers have successfully extended their global export reach out of necessity. They’ve done so partly because of the European Union’s low duty-free quotas in its agreement with Ukraine.

EU quotas

In the first two weeks of 2017, sugar exporters exhausted 64 percent of this year’s white-sugar quota to the EU, which totals 20,000 tons. In 2016, the EU quotas for sugar, as well as honey, chicken, corn and other grains, were used up.

However, given that Ukraine has the capacity to produce 2 million tons of sugar per year, the duty-free quotas cover a tiny share of output.

“We were promised the boundless horizons of the European market, but unfortunately we couldn’t obtain (bigger quotas),” said Andriy Dykun, the head of the country’s sugar association Ukrsugar. “The Europeans don’t want to see Ukrainian sugar on their shelves, because they’re afraid, as they know perfectly well that Ukraine can make better (products).”

More than half of the EU export quota was used by Astarta last year, said Kovalskiy, and once the quota is used up, it’s no longer profitable to sell Ukrainian sugar in the EU. “Beyond the quota, sugar exports to the EU are economically impossible,” Kovalskiy said.

Dykun said that while Ukrainian grain has made the nation the “breadbasket of Europe” since Soviet times, the country’s refined sugar doesn’t enjoy a similar demand.

Foreign investment

After the Soviet Union collapsed, demand for sugar dropped in Ukraine, 25 years later, only 42 sugar plants out of the 192 that used to work remain operational.

But thanks to foreign investment, more plants should open soon. In Ternopil Oblast, once a leading region in the sugar industry, Germany’s Pfeifer & Langen has bought six plants that process beets into white sugar, only one of which is operating. The company owns two other plants, Radekhiv Plant in Lviv Oblast and Chortkiv Plant in Ternopil Oblast, both of which were built in the 1970s.

“People who invest in the country wartime should get an ‘honored investor’ award,” Dykun said of the German company.

But the decline in the hrvynia’s value and its already established presence made expansion a good bet. Dykun said the industry has lots of potential for growth, but needs lower interest rates and support from the government, such as a cut in customs duties for imported sugar-refining equipment.

“If Ukrainian sugar and beet producers got the same financing as the industries in Europe or U.S. do, we’d fill the whole world with sugar,” he said.