Every year, Ukraine loses at least $50 billion a year to tax evasion.

In May, the government passed a law to stop the illegal flow of money out from the country, but businesses fear it could hurt legitimate cross-border

transactions.

Under this new law, Ukraine-based business owners will have to declare revenues from foreign assets, or they could face a steep fine on their income.

The so-called “BEPS law” (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) aims to fight offshoring by tracking and taxing profits earned by Ukrainian citizens worldwide. But some Ukrainian businesses have labeled it a “terror tax,” believing it may hurt them.

That draws a laugh from Constantin Solyar, partner at the Asters law firm and a leading Ukrainian tax expert. According to him, the law only targets abusers.

“The government took an unexpectedly strong stance against offenders,” Solyar said. Still, he thinks it is too early to say how much money it could bring in.

Lax rules

The law introduces Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) rules: Ukrainian business owners will have to declare their companies, trusts and partnerships abroad and pay taxes on them starting on Jan. 1, 2021.

Ukraine is ranked 64th out of 190 economies in ease of doing business, according to the latest World Bank annual ranking. Ukraine’s rating

improved to 64 in 2019 from 71 in 2018. Source: World Bank

Offshore and shell companies are a common feature in Ukraine, where shady businesses often use tax havens like the British Virgin Islands or the Bahamas to hide their assets. The CFC rules aim to change that.

This move is in line with a global tax transparency trend, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Inclusive Framework, which works to impove the coherence of international tax rules. Ukraine signed the framework in 2018.

Ukrainian business owners will have to pay 18% of their income from foreign companies in taxes if they declare themselves as individuals and 19.5% if they declare themselves as entrepreneurs. But the tax will be reduced to 10.5% if the foreign company’s profit is declared as dividends.

Solyar says the law provides for broad tax reductions, so small businesses will not be hurt in the process.

“The law is flexible enough for businesses,” he said.

The government has passed a new law that aims to fight offshoring by tracking and taxing profits earned by Ukrainian citizens worldwide. Under this new law, Ukrainebased business owners will have to declare revenues from foreign assets, or they could face a steep fine on their income. (Kyiv Post)

The BEPS law applies to business owners who control a foreign company, meaning that the owner holds more than 50% of its shares or, if he controls the company with a partner, that he owns 25%.

However, if he declares less than $2 million dollar in income per year or if the company is a charity or listed on a stock exchange, he will not pay taxes.

If he pays taxes, he will only pay them on 60% of the profits of his foreign company.

The law also provides for exemptions when Ukraine has signed a tax convention with the country where the business is located. If the company already pays taxes (from 13%), and if half of its revenues comes from dividends or royalties, there is no need to pay taxes but the Ukrainian business owner still has to report the revenues.

Ambiguous law

Under the new BEPS law, companies based in Ukraine will also have to prove that they do not use foreign companies as empty shells starting on May 23, and they fear it might hurt basic transactions.

Solyar said the so-called “business purpose” provision would increase paperwork and add to the administrative burden if companies sign contracts outside Ukraine.

“Companies are afraid that respecting regulation abroad will bring them trouble in Ukraine,” he said.

Viktoriya Fomenko, partner at law firm Integrites, told the Kyiv Post on June 22 that the clause might be burdensome for Ukrainian businesses.

“For a Ukrainian business structured via foreign jurisdictions, the law is quite challenging,” she said.

She also said the law is not clear enough.

“Such ambiguities may be seen as (punitive) fiscal measures against taxpayers,” she said.

Anastasiia Solomatina, who works for the European Business association, concurred with Fomenko. She said businesses need to have clearer information.

“Clarity about tax rules is essential for businesses,” she said.

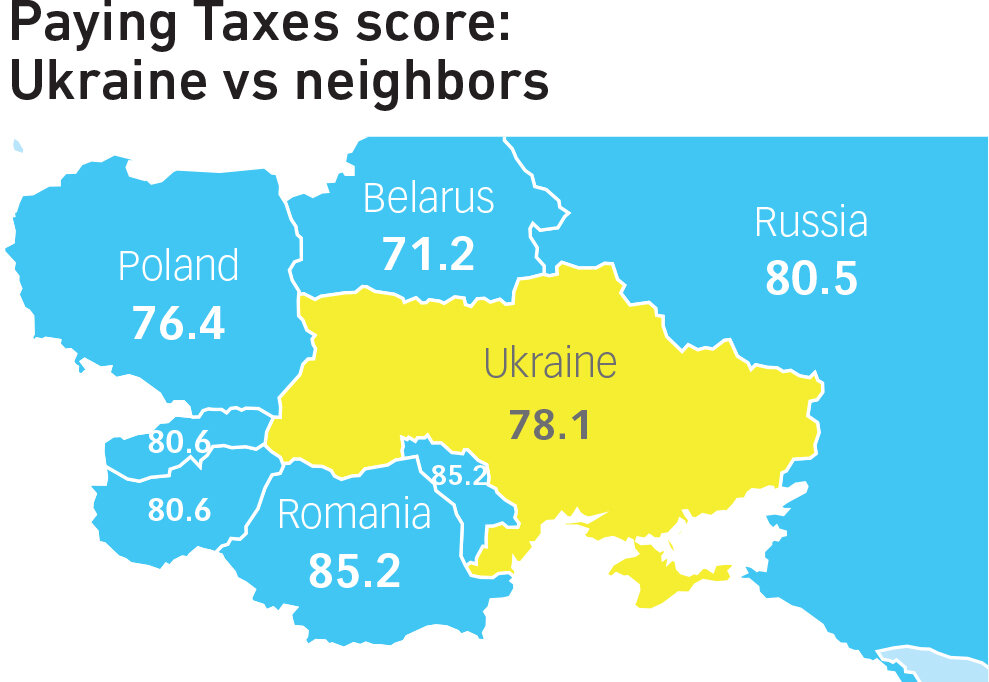

The Paying Taxes score shows how easy and transparent it is to pay taxes across 190 economies. Bahrain, a country in the Middle East, received the best score in this ranking (100), while Venezuela got the worst (11.4). Sources: PwC

Ukrainian offshore

Still, taxes can also bring investments, according to Solyar.

Ukrainians who own a foreign company may receive advantages and pay less taxes if they register their assets in Ukraine. The relocation, allowing them to pay 10% of less, might create an “internal offshore” system, he said.

“You can go big thanks to low taxes,” he said.

The law also offers tax-free liquidation of assets if the business owner voluntarily reports his assets by December 31.

However, “this is an exemption, and not an amnesty,” Solyar said.

Lack of trust

For Solyar, the real issue is not taxes, but trust.

Ukraine committed to join the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) on the automatic exchange of information about Ukrainian financial accounts by the end of 2020. It should come into effect in 2021.

The exchange of data was already adopted in dozens of jurisdictions, including the U.K., the EU, Russia, China and many other countries (the U.S. and its banks exchange such data on request, but not automatically).

Tax reports constitute the backbone of the BEPS law and the CRS. Even if these rules were amended to include bank secrecy, business owners are defiant, Solyar said.

Businessmen are concerned that the law could give too much power to Ukrainian tax authorities and law enforcement, he said. “They do not trust the government and fear that information is going to be leaked.”

In Ukraine, reporting income often means unlawful harassment and persecution by the tax authorities, Solyar said. Investment can only be attracted when the government is reliable.

“We have these resources,” he said. “What we don’t have is the trust in our rule of law.”