When it comes to energy efficiency, there’s more talk than action from Ukraine’s government and lawmakers.

Ukraine has only recently started to take measures to improve energy efficiency — the kind of measures that have been common practice in the rest of Europe for more than 20 years. Much of the energy waste occurs in Ukraine’s Soviet-era centralized building heating systems, which are badly in need of modernization or replacement by individual heating systems.

The scale of the problem is huge. Ukraine’s housing sector — including public buildings and heating networks — wasted 10 percent of its heat energy, or 93.3 million gigacalories, and 7 percent of its electricity, or 144.9 billion kilowatts, in 2017 due to energy inefficiency, according to Ukraine’s State Statistics Service.

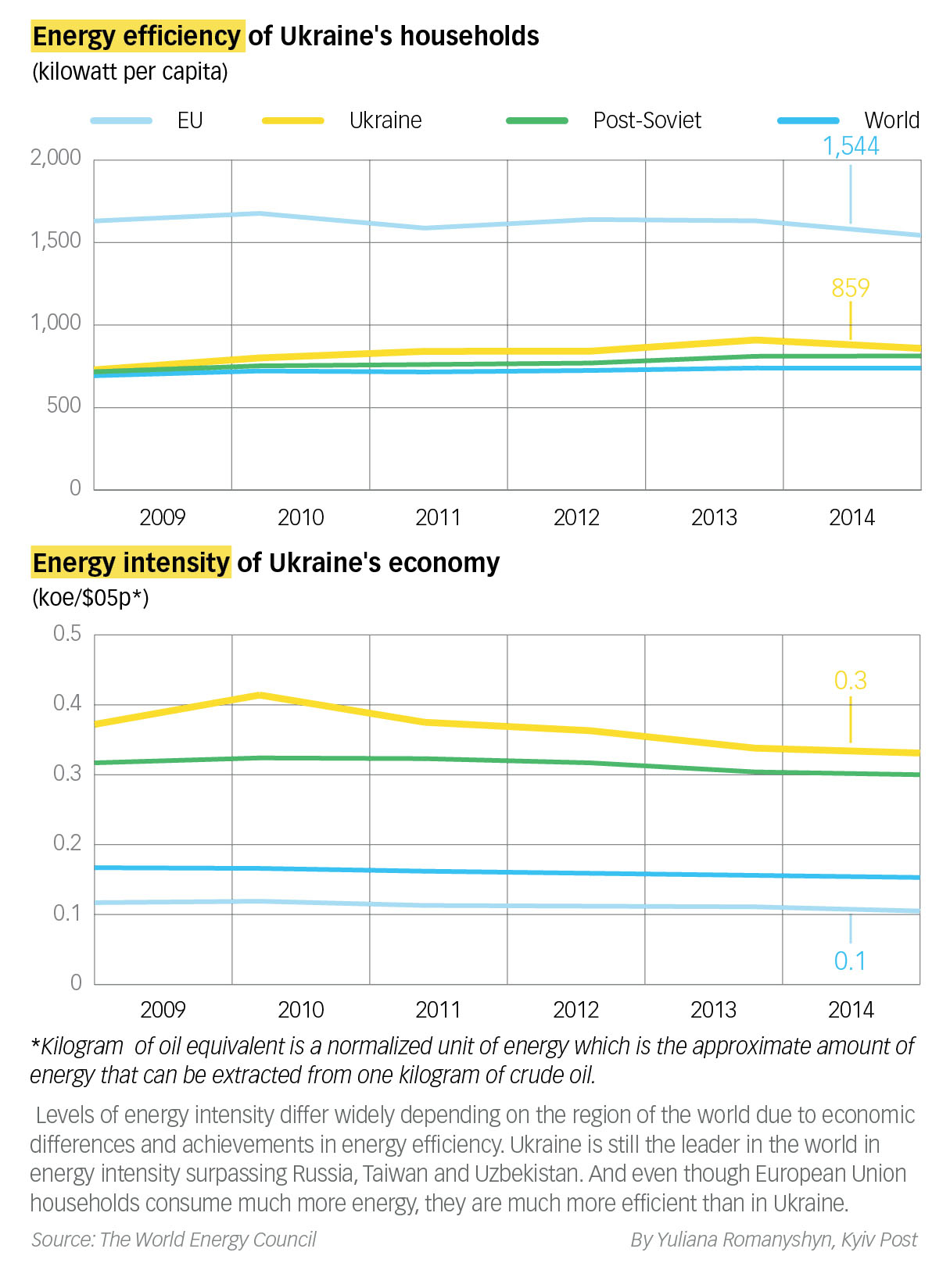

Ukraine’s energy intensity is more than three times higher than that of Germany. Ukraine’s energy intensity, or how much energy it takes to produce a unit of GDP, in 2015 was 0.246 kilograms of oil equivalent per dollar of GPD. In Germany the figure was 0.07, according to the Global Energy Statistical Yearbook.

Gas price hikes

And things aren’t improving: In 2013 Ukraine jumped ahead of Uzbekistan to become the world’s energy intensity leader. It remained so for four consecutive years, and is likely to be so again this year.

The high level of energy intensity is due to Ukraine’s economy being heavy on commodity production while having relatively low energy prices.

Nevertheless, Ukraine has in recent years had to raise domestic natural gas prices to market levels as one of the conditions for receiving further low-interest loans from the International Monetary Fund. Ukraine has still only received half of the conditionally approved $17.5 billion in credits under the program, which expires in March 2019.

The increase in gas prices has bumped up utility bills for Ukrainians over the past four years: the cost of heating went up by three times, electricity by four times, and gas by nearly six times. At the same time, the official average wage has halved since 2013, sinking to $246 per month in 2017.

This created another problem: a large chunk of Ukraine’s $40 billion state budget goes toward subsidies for those who can’t afford to pay their utilities bills due to the price hikes. More than half of Ukraine’s population — almost 25 million people — qualified for the subsidies, which totaled Hr 26 billion or around $1 billion last year. But that’s paying people to maintain their current levels of energy consumption, not encouraging them to consume less.

“Ukraine needs to save energy in startling amounts, because it is the biggest consumer per capita in the world,” said Andreas Helbl, general director of iC Consulenten, an engineering-consulting company, told the Kyiv Post.

iC Consulenten has been operating on the Ukrainian market since 2006, serving as a link between international financing institutions, Ukraine’s government and municipalities to organize energy efficiency projects.

“And when you have a very high level of consumption it means that you’re also spending a lot of money on supplying that energy,” Helbl added.

Warm loans

But while utility prices have soared (and they are expected to go even higher), many Ukrainians have lacked the resources to make their housing more energy efficient.

In response, the government launched its Warm Loans initiative in 2014 — a public program aimed at partially subsidizing interest rates on loans taken by the public from state banks to make their homes more energy efficient.

This year, the government allocated Hr 400 million ($15.3 million) from the state budget for the program, which is run by Ukraine’s four largest state banks — Ukrgasbank, Ukreximbank, PrivatBank and Oschadbank. Ukrgasbank has taken the lead in offering the public “warm loans.”

“We’ve been working with this program from the very beginning, and probably half of all of these ‘warm loans’ — more than 55,000 loans worth a total of Hr 1.2 billion ($46 million) — were granted by Ukrgasbank,” said Oleh Kliapko, the head of Ukrgasbank’s retail banking department.

Since the beginning of this year, however, some changes have been made to the legislation. Now only owners of private houses that have no more than three floors, or the housing cooperatives of multi-story residential buildings qualify to receive such a loan from the state banks, according to Kliapko.

IQ Energy

Overall, around 215,000 loans were given to residents during 2015-2017 for the implementation of energy efficiency measures in Ukraine, according to Helbl.

Another energy efficiency program called “IQ Energy,” run by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, offers to cover up to 35 percent (but no more than 3,000 euros) of the cost of energy efficient products for saving energy in a house or apartment.

Residents are given the subsidies within 3–5 weeks of the approval of their electronic application being submitted to the program at its website, iqenergy.org.ua. A further condition is that the money is granted only to individuals who purchase materials using a loan from the following banks: Ukrsibbank, OTP Bank, Raiffeisen Bank Aval or Credit Agricole.

Since 2016, more than 12,000 loans have been granted to Ukrainian residents through the “IQ Energy” program.

Local initiative

Changes are happening at the municipal level as well: Ukrainian local officials have become better at understanding how to implement energy efficiency projects offered by international financial institutions.

Ima Khrenova-Shymkina, the deputy director of the “Energy Efficiency Reforms in Ukraine” project, carried out by Germany’s state-funded GIZ non-profit organization, says that GIZ has been working to train municipal officials on how to be better and more efficient managers.

“After city officials in Zhytomyr learned how to work (better), the average period for the implementation of energy efficiency projects was reduced to one year,” said Khrenova-Shimkina.

The results are starting to become clear.

More than 100 municipal energy efficiency projects in Ukraine, covering almost every oblast, are now being financed by the Nordic Environment Finance Corporation (NEFCO), according to Julia Shevchuk, NEFCO’s chief investment advisor.

The EBRD is also providing more than 100 million euros to finance energy efficiency projects for public buildings in 10 Ukrainian cities.

The city of Kremenchuk was the first one to receive financing, gaining a total of 10 million euros to improve energy efficiency in 38 kindergartens, 23 schools and four hospitals.

In the beginning, however, it was difficult to start any energy efficiency project at the municipal level.

Such was the case in Ivano-Frankivsk in 2012, when this western Ukrainian city became the first to attempt to implement a local energy efficiency program.

“Six years ago… the very first tender on energy efficiency upgrade programs for buildings (in Ivano-Frankivsk) received zero applications, as no one was prepared to meet the requirements of the German partners,” Khrenova-Shymkina said. “That’s even though 40 percent of the project would have been compensated for.”

Barriers

Still, Ukraine faces several immediate barriers blocking the way to creating a more energy-efficient housing sector.

For example, doing all the paperwork just to apply for a modernization project at a typical kindergarten in Ukraine takes on average three years. It takes 3–5 years to arrange a project to modernize municipal public buildings and district heating boilers.

“This is simply too long, given the scale of the modernization required in Ukraine,” said Elena Rybak, the director of the European-Ukrainian Energy Agency.

At the same time, applying for a tax exemption for an energy efficiency project usually takes around three to six months, with hundreds of documents having to be filled out, according to NEFCO’s Shevchuk.

“Every year we have a new problem created by the government, and we then have to try to solve it,” she said.

Ukraine also lacks qualified energy auditors who can work according to European Union standards, said Johannes Baur, the head of the Energy, Environment and Transport Section of the Delegation of the European Union to Ukraine. On top of that, there are no consistent and standardized building energy efficiency standards, which complicates the energy efficiency modernization process.

But the most important challenge in Ukraine is the mentality of the public, according to Baur.

“You cannot just rely on the city or on the government for everything,” he said. “It’s a person’s own responsibility to organize the modernization of their house.”