Outside the business community, the term “transfer pricing” sounds like jargon.

But for tax agencies and national budgets, controlling it is extremely important.

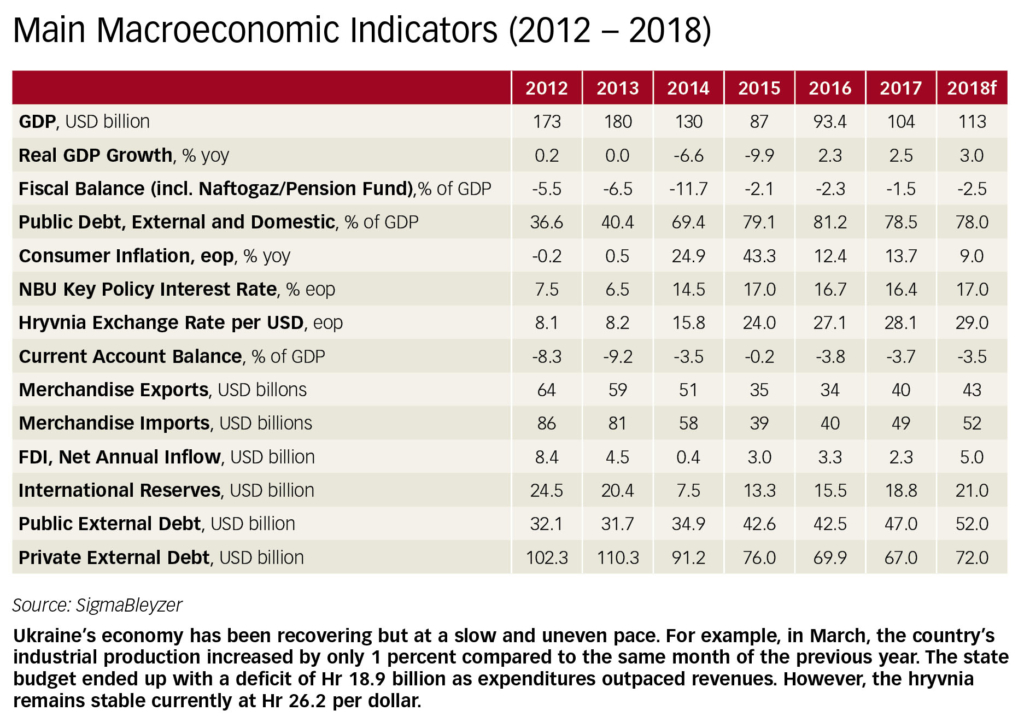

Companies that use transfer pricing schemes to avoid taxes are costing Ukraine’s state budget an estimated Hr 50 billion, or nearly $2 billion, per year, according to Tetiana Ostrikova, a member of parliament who is on the tax committee.

In accounting, the term describes transactions that take place when two related companies in different countries trade with one another. There’s nothing inherently illegal about that, but businesses can use these sales to transfer assets to subsidiaries in tax havens at deflated prices to shirk their tax responsibilities.

With so-called “offshoring” increasingly coming under global scrutiny and more governments moving to regulate these transactions, transfer pricing compliance services are a growing industry.

In the tax sector, “transfer pricing is the hottest topic not only in Ukraine…but also worldwide,” says Konstantin Karpushin, a partner at KPMG in Ukraine. “Many countries have already implemented rules and the number of countries that introduced legislation is increasing.”

But, to many experts, transfer pricing regulation in Ukraine remains a work in progress — and, potentially, an area for innovation.

Changing legislation

For 20 years of independence, Ukraine was part of a legal gray zone for international trades between related companies. It had no legislation governing transfer pricing.

Then, in 2013, the Ukrainian government introduced regulations. The first legislation drew inspiration from a Russian law passed in 2011 and focused on the pricing of goods and services.

However, in the ensuing years, the country transitioned to legislation based more upon standards established by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development.

That has shifted the legislation’s focus away from controlling pricing to controlling transactions. OECD standards require that companies hold related party transactions at “arm’s length” and apply the same market valuation approach they would use with unrelated companies.

This move toward a more European law has direct benefits for multinational corporations operating in or planning to enter the Ukrainian market, according to Karpushin.

“It’s more understandable for them, so the compliance cost is lower,” he says.

Recently, updating the transfer pricing legislation has become an annual tradition in Ukraine.

In the last two years, amendments to the law have widened the types of “controlled operations” to which transfer pricing regulations apply, increased the amount of information that should be included in transfer pricing reports, and implemented new fines for violating the law.

But the new amendments also make some adjustments that will benefit taxpayers. Transactions are traditionally recognized as “controlled” if the taxpayer’s annual income and annual volume of transactions with non-resident entities cross a financial threshold.

In 2013–2017, that threshold was set at an income of Hr 50 million ($1.9 million) annually and Hr 5 million ($190,000) in transactions. Now, these standards have been raised to Hr 150 million ($5.7 million) and Hr 10 million ($381,000), respectively.

Lawmaker Tetiana Ostrikova, who sits on the parliament’s tax committee, says that abuse of transfer pricing costs Ukraine nearly $2 billion in tax revenues annually. (Ukrafoto) (Chumachenko Alexey)

The most recent legislation also moves the deadline for submitting transfer pricing reports to the tax authorities from May 1 of the year after the reporting period to Oct. 1.Both adjustments decrease the burden on small and medium businesses, which often struggle to provide transfer pricing documentation. Additionally, the longer deadline for reports not only allows companies more time to prepare their documents, but also helps some firms “that cannot know the final results of their activities” by May, says Dmytro Rylovnikov, a senior associate at the DLA Piper law firm.

However, not everything has been simplified. The new legislation also increases the number of cases when transactions — even between non-related parties — must undergo transfer pricing checks.

These cases include transactions with certain types of legal entities and with companies in jurisdictions with corporate tax rates lower than in Ukraine by at least 5 percent or where the authorities do not reliably provide tax information to the Ukrainian government.

As of Jan. 1, transactions with 85 countries require transfer payment checks.

Theory versus practice

For his part, Rylovnikov says the new laws have delivered.

“I can’t say it’s ineffective,” he says. “Checks are happening, there are results and additional tax charges… companies get requests (for information) from the tax authorities, and if a company has questionable transfer payments, they often submit corrections.”

Still, although Ukraine’s legislation increasingly meets international standards, transfer pricing enforcement — as with many things in the country — differs in theory and practice.

“If you compare it with other developed economies, there the checks end with many more additional tax charges and they’re often dozens of times larger,” Rylovnikov says.

Serhiy Golovniov, an investigative journalist who has actively covered tax evasion schemes, also has his doubts. Before 2013, the general situation was “total chaos, and everyone did what they wanted and no one controlled it,” he says.

When the transfer pricing law came into force, Golovniov and his colleagues followed it closely, but didn’t see the results they expected.

“As far as I can judge, many things have remained the same — at a minimum when a major holding sells its products for a lower price to a company in an offshore jurisdiction, which then sells it for a market price…” he says. “And it’s not only to offshore jurisdictions, but also to companies registered in Switzerland, Australia, Cyprus.”

However, KPMG’s Karpushin blames these issues on implementation, not legislation.

The law, he says, is strong and sound. And, according to the State Fiscal Service, it is working. In 2016, Ukraine saw Hr 2.6 billion ($99.3 million) in voluntary tax adjustments, the Service said in a statement. That means taxpayers who believed they had violated the arm’s length principle voluntarily adjusted their documentation and paid more taxes.

The problem, Karpushin says, is resources. He estimates that around 10 people work on transfer payments in the State Fiscal Service. That number should be increased to roughly 50, he says.

Moreover, Karpushin believes that it is not enough to simply receive transfer pricing reports and scrutinize them in an Excel spreadsheet. Instead, he thinks the Ukrainian tax authorities should use algorithms, big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence to analyze all the received reports and decide which companies to audit.

Ukraine has the developers, programmers, and coders necessary to develop such an automated analytical program. And with transfer pricing a rapidly growing subject in global accountancy, there is a short window of time for Ukraine to create something innovative, Karpushin says.

“Maybe it’s time not to look to other countries, but to build something here and show them.”