If there’s one tax that Ukraine should increase, it’s the property tax.

An estimated 90 percent of Ukraine’s population is exempt from paying taxes on their real estate. And those who are required to do so have to pay very little to the government.

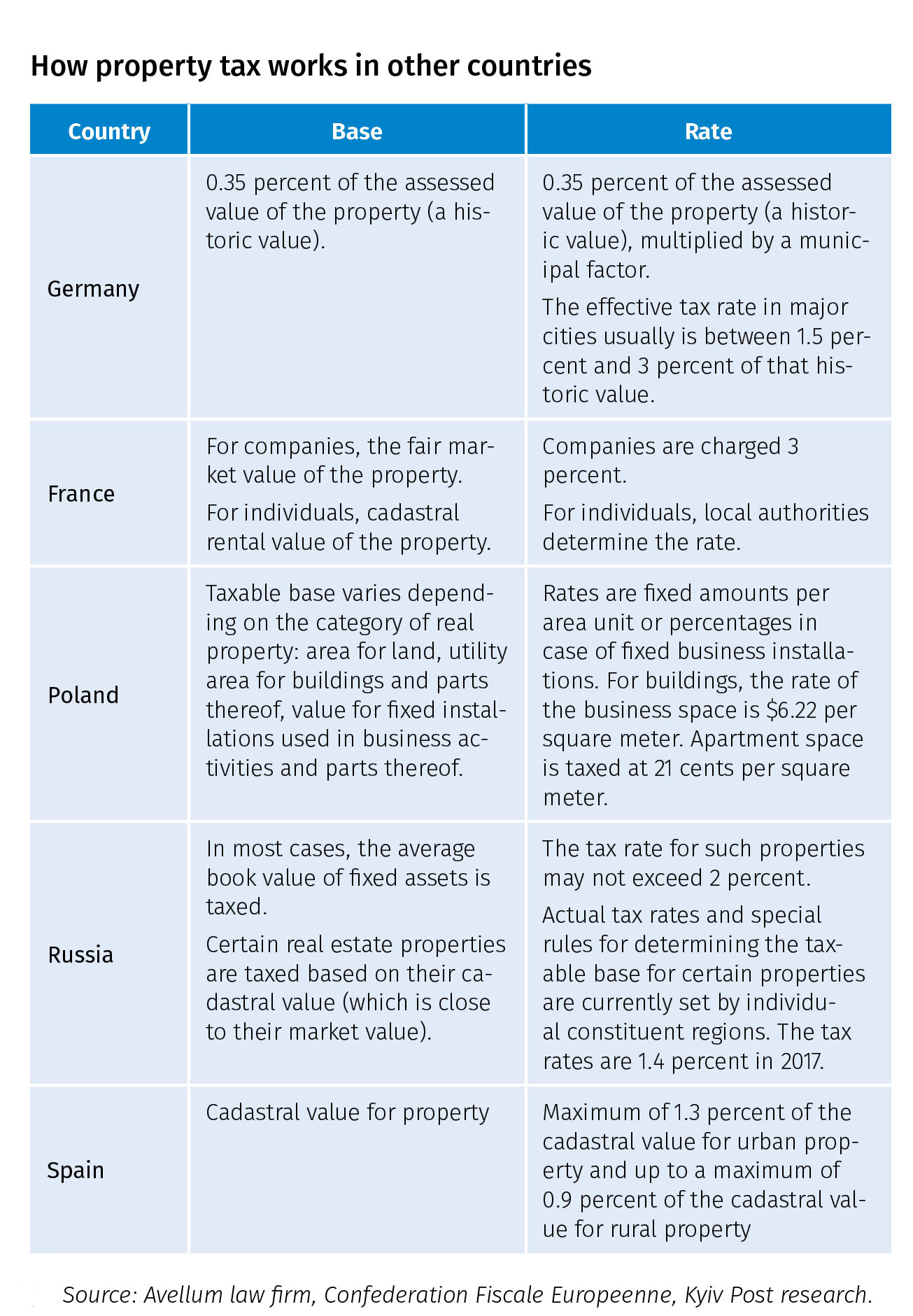

Although fairly new to Ukraine, the idea of paying tax on property is hardly a novel concept.

Most developed countries apply such taxes, in significant amounts annually, to boost local government revenues. Property taxes go to finance police, roads, schools and a host of other public services at the municipal and regional levels. The more valuable the property, the higher the amount of property tax assessed.

Vadim Medvedev, a lawyer with Ukrainian law firm Avellum’s tax practice, says that Ukraine should not overlook the tax as a way to raise revenues.

“Ukraine definitely has bigger problems… but still this tax is very important, because it is a tool used worldwide to improve local budgets,” he said.

This tax also “decreases the wealth gap,” Medvedev said, by forcing wealthier citizens in wealthier homes to pay more for government services.

But Ukraine’s rich have little to fear from Ukraine’s property tax. Introduced only a few years ago, back in 2012, it still only raises a tiny percentage of Ukrainian cities’ overall budgets. In Kyiv, for example, the tax contributed less than 1 percent of the city’s overall budget in 2016. By contrast, in Fairfax County in the state of Virginia, property taxes accounted for more than 60 percent of local governments’ revenue.

Property taxes are a major source of government revenue in the West, but only 2 percent of Ukraine’s tax base. Moreover, Ukraine’s government assesses propery tax based on size of dwelling rather than on the market value of the property.

Ukraine’s tax

In Ukraine, most real estate owners are exempt from the tax. Owners of apartments do not need to pay if they live in apartments that are under 60 square meters; most apartments are this size or smaller. Owners of houses do not need to pay if the property is under 120 square meters in area, as most such homes are.

“The tax started with residential real estate only, and then it was expanded to other types of real estate, like commercial,” Medvedev said.

Real estate that is exempt from the tax includes production and storage premises, hospitals, agriculture production sites and other industrial sites.

The formula for calculating the tax is also odd, compared to the West, where property is assessed for taxes based on its market value.

In Ukraine, the property tax is up to 1.5 percent of Ukraine’s minimum salary (Hr 3,200). That is then multiplied by the area of the property above the tax-exempt area of 60 square meters for apartments and 120 square meters of housing.

Municipal governments have the power to charge less than the 1.5 percent rate, but not higher — only the central government can increase the capped rate. Over the past three years alone, the cap has jumped back and forth, from 1 percent to 3 percent to the present 1.5 percent.

But it actually makes little difference whether the rate is 1 percent or 3 percent, since the amounts raised are so low. The owner of a 90-square-meter apartment pays less than $60 per year with a rate of 1.5 percent.

By contrast, in Washington, D.C., the owner of a small 51 square meter apartment with a market value of $237,000 pays $1,400 in property taxes each year.

And even if someone in Ukraine owns an apartment larger than 300 square meters or a house larger than 500 square meters, the annual tax will be only an additional Hr 25,000 (less than $1,000). Lawyers say, however, that in practice, there are very few who can afford such properties.

Value vs. square meters

Ukraine’s universal property tax formula fails to account for regional variations in property value. Prime property in downtown Kyiv is taxed at the same rate as property in Lviv or Odesa.

“The area of the building is not the best indicator of how valuable it is,” Medvedev said. In other countries such as France, Germany and the United States, property taxes are based on a property’s market value.

But Roman Drobotskiy, a senior associate at Kyiv’s Asters law firm, says that Ukraine is not ready to switch to a value-based system. The problem? It is practically impossible to value property accurately in Ukraine.

Ukraine doesn’t have an “instrument that allows the calculation of a fair market price of a property,” he said.

The problem is compounded by the fact that the country’s real estate market is distorted, with many properties overvalued. That’s because of the weakness of the national currency, the hryvnia, and the public’s distrust of banks. People tend to use real estate as bricks-and-mortar piggy banks to protect their savings from devaluation.

Real estate taxes are a relatively new concept for Ukraine, in effect only since 2012. But such taxes are a major source of government revenue in many Western nations.

Empty buildings

The dysfunctionality of the tax system is even more apparent when the number of empty buildings in Kyiv is taken into account. Because of the minuscule property tax, property owners who use empty apartments as a way to store value have very little incentive to sell for anything less than a goldmine deal. As a result, Kyiv has high demand for real estate, lots of supply, but few buyers because of low wages and overblown prices.

The system also has loopholes which allow builders to avoid the tax even if they have completed a building — they will not register the building with the tax authorities until the property is sold.

“The tax is applicable to the owner whose real estate is registered in the state register,” Drobotskiy said. “So until the property is registered, the tax is not applicable.”

Practical solutions

Despite its flaws, Ukraine’s property tax system could work, however. Countries like Poland and the Czech Republic also base their property taxes on area, as they too are still struggling to find a real estate valuation system. Their systems are more successful because their tax rates are higher and collection much more efficient.

“The first and most important thing is just to collect the tax we have now properly,” Medvedev said. “That would mean bringing Ukraine’s real estate register fully up-to-date, as the local authorities are still missing a lot of information.”

Drobotskiy agrees. “The problem is not in the taxing, it is in the administration,” he said. An electronic system would fix many of the problems, as the tax authorities are still working with hardcopy documents on each property owner.

“The tax authorities are actually physically unable to do this amount of work,” Drobotskiy said. “In fact, in many instances they don’t even send a tax notification to people, and people just don’t pay this tax.”

If taxpayers don’t get a property tax bill within three years, they do not have to pay.

Another possible solution is to establish a tax system based on city zones or “regions,” Avellum’s Medvedev said. For example, in Kyiv the cadastral or assessed value of a property could be based on the minimum price of a square meter, which is close to $600. “We could easily tax all properties on this cadastral value, and then the tax would be significantly higher,” Medvedev said.

Another option is to simply increase the tax or decrease the tax exemption figure to make the tax-exempt square meter threshold lower, to 30 or even 20 square meters.

“Then the amount of taxable property will increase significantly,” Drobotskiy said.