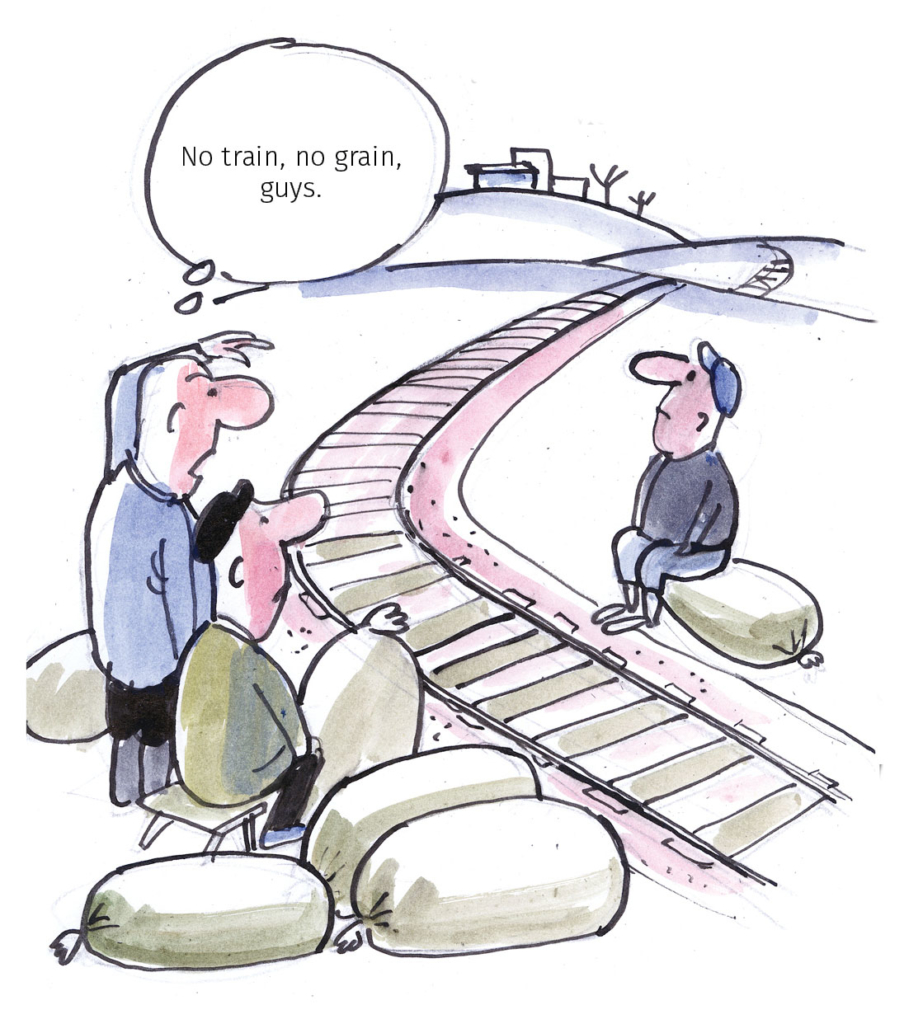

Ukraine’s thriving grain industry outstrips the capacity of its railway system.

While the country exports two-thirds of its grain, further expansion relies on state railroad monopoly Ukrzaliznytsya, which hauls crops from fields to Black Sea ports.

In 2015, the government banned trucks with more than 40 tons of freight from driving on highways to preserve Ukraine’s crumbling roads. Grain producers were forced to switch to the railways, but a sharp surge in demand exposed aging infrastructure, a shortage of railcars and poor management.

Shortage of rail cars

Last December farmers in Lviv Oblast found themselves in a difficult situation. Harvesting of corn was delayed because elevators were filled with stored grain destined for export. Farmers blamed railway authorities for the absence of empty grain cars. “They couldn’t export grain from elevators to ports for several weeks,” head of Ukraine Grain Association Mykola Gorbachov said.

Currently, Ukrzaliznytsya operates 18,000 grain hoppers, enough for grain exporters if they were used efficiently, Gorbachov said at a press briefing on March 15. “Poor management of resources is evident: there are more wagons with lower turnover, and we are short of wagons again.” Large grain storages receive priority service, according to the association. There are only 50 able to load .a full fleet of 54 wagons in one shipment. The 800 smaller elevators have to wait. “We want Ukrzaliznytsya to show us the algorithm of distributing grain cars and locomotives among stations,” Gorbachov said.

Ukrainian grain exporters report severe shortages of rail cars to transport their grain to the ports. The problem has been worsened by a 2015 ban on road freight loads over 40 tons, meaning more grain has to be transported by rail.

Yuriy Skychko, a director of Hermes Trading, corroborates that lack of transparency harms exporters.

Hermes Trading sells abroad some half a million tons of grain a year, which makes it one of the leading grain exporters in the country. Yet it falls short compared to the largest agroholdings that load 54 wagons and more at once.

“Our elevators are capable to load 18–20 wagons, but we don’t get the requested number of railcars from Ukrzaliznytsya. They send 2–5. As a result, our deliveries to port to our buyers fail. We lose profits,” he told the Kyiv Post. “We have to work in such unpredictability, never knowing how many empty grain cars we will receive or how quickly they will be unloaded.”

The railway officials deny any discrimination and blame grain producers for not providing data on planned exports.

Recently transformed into a state-run corporation, Ukrzaliznytsya made a profit in 2017 for the first time in years and plans to increase earnings by optimizing its freight department.

According to the company’s financial director Andriy Ryazantsev, over a half of a total of 518 stations operate at a loss due to small loads of grain from elevators. “It is a luxury to run a wagon of grain with two locomotives,” he said. To cut costs, the company suggested consolidating shipments from several elevators and closing unprofitable stations.

“We will also change the application process and engage elevators that confirm they have grain in storage for export,” Ryazantsev said at a press briefing on March 15.

Gorbachov of the Ukraine Grain Association believes such an approach is wrong. “Ukrzaliznytsya is a monopolist, and their purpose is to meet the needs of important sectors of economy like agriculture, not increasing its own profitability,” he said.

Upgrading the fleet

While Ukrzaliznytsya struggles to keep up with current volumes of 40 million tons of grain a year for export, grain producers forecast a doubling of volume in the next decade. This will require significant improvement in railway logistics and upgrading an old fleet of locomotives and grain hoppers, most of which were bought back in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Aware of the looming crisis, Ukrzaliznytsya signed a 10-year, $1 billion deal with American corporation General Electric in February. The deal foresees purchasing 200 locomotives from GE, with the first batch of 30 locomotives slated for delivery this year. In addition, the company plans to purchase 350–500 grain hoppers through tenders.

In March, Ukrzaliznytsya reported talks with German Siemens AG on joint manufacturing of locomotives. But this prospect is doubtful, since a 2018 financial plan shows no investment into construction.

The financial director of Ukrzaliznytsya, Ryazantsev, said that his company intends to start building grain hoppers in 2020. So far Ukraine only makes open wagons and container platforms.

A freight train station in Odesa on July 22, 2017. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

Market liberalization

Delegating some railway services to private operators could relieve the emergency, but Ukrzaliznytsya doesn’t allow privately-owned locomotives on its tracks.

The situation will have to change, however. The political and trade Association Agreement with the European Union, which came into force last September, favors the creation of an open railway market in the next seven years. And Ukrzaliznytsya is looking for a mechanism to fit in the European model, in which a monopoly infrastructure operator gives access to independent train operating companies.

At the meeting with a logistics committee of the European Business Association on March 2, acting head of Ukrzaliznytsya Yevhen Kravtsov said his company supports opening the market, especially on unprofitable routes, but doesn’t want to lose its dominant position and profits.