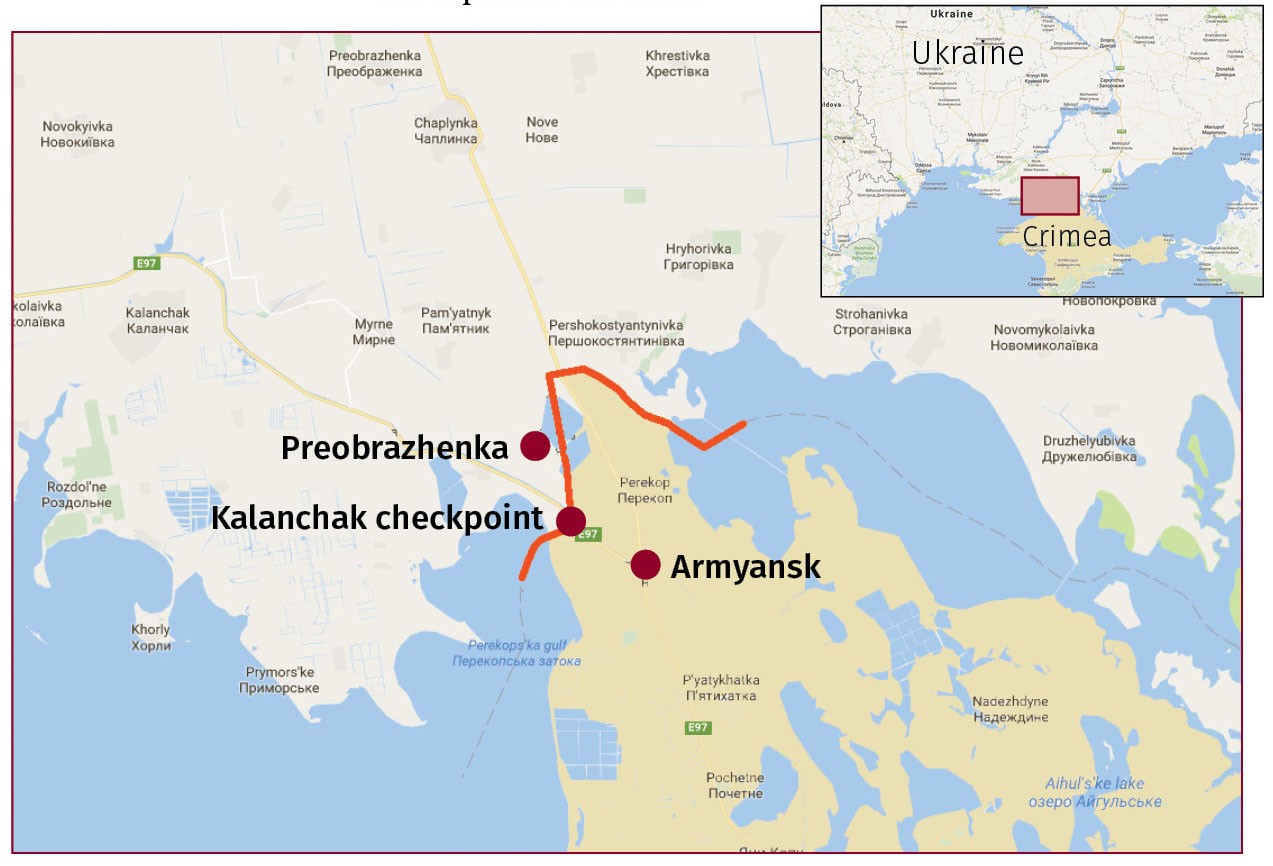

PREOBRAZHENKA, Ukraine – One by one, about a dozen men pass through the last barricades at Ukraine’s Kalanchak checkpoint from the border at Kherson Oblast and prepare to enter Russian-occupied Crimea.

With backpacks slung over their shoulders, they stroll towards a mini-bus waiting for them about 100 meters from the checkpoint.

The absence of heavy luggage and their tired, everyday demeanor is a giveaway – these are not returning tourists. These are employees of a chemical plant named Crimean Titan. And crossing the border is a part of their daily commute to work.

The titanium producer is the biggest employer in Crimea’s Armyansk, with around 4,800 employees from the city – which has 21,000 people – working at the plant.

Prior to Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, the titanium producer employed around 700 workers from mainland Ukraine, primarily from small villages near the border in Kherson Oblast.

Today less than 100 workers – largely from the Kherson Oblast border settlements of Preobrazhenka (formerly known as Chervony Chaban) and Pershokostyantynivka – remain.

The largest producer of titanium in Eastern Europe, used in wide range of products from plastics to cosmetics, the plant manufactured 101,000 tons of titanium dioxide in 2014.

Controlled by Ukrainian oligarch Dmytro Firtash’s Group DF, it was re-registered as Ukrainian Chemical Products in Ukraine and Titanium Investment in Russia, following Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea.

Oleg Arestarhov, Group DF’s head of corporate communications, told the Kyiv Post that the company would not comment on matters relating to the titanium plant. “From 2014 our press office hasn’t been answering any requests about our Crimea assets because any comment about Crimea business will be political,” he said.

A worker told the Kyiv Post that employees have also been discouraged from speaking with media. The Kyiv Post has withheld the names of all employees interviewed for this article because they fear being fired for speaking publicly.

Complex situation

Some 530 kilometers southeast of Kyiv, Kalanchak is one of three customs checkpoints on the border between Ukraine’s Kherson Oblast and Russian-occupied Crimea, where pedestrians and vehicles can cross.

One longtime titanium plant employee uses both Kalanchak and Chaplynka checkpoints on his daily commute to the plant. The worker said the situation at the border has evolved since Russia’s annexation of the peninsula in 2014.

“In 2014 it took us six hours to get to work. There were insane lines. Trucks stood here for months,” he said.

In late September 2015, hundreds of trucks were detained at the border, including the Kalanchak checkpoint, after a group of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian activists launched a blockade, preventing food and other goods from entering Crimea.

By the end of 2015, the Ukrainian government voted to enforce trade restrictions with the occupied peninsula, which came into effect mid-January this year.

The worker said while the situation at the border is now much calmer, there are still occasional delays.

“A month or two ago, we were still waiting for a long time,” the worker said. “There was only one border window working, and cars as well as pedestrians were all waiting in the one line. We would get there at 6 a.m., and at 8 a.m. we would still be waiting.”

The Kalanchak checkpoint in northern Crimea sees Crimean Titan workers living in Ukraine cross daily onto the Russian-occupied peninsula every day.

In early August, Russian authorities shut down the Kalanchak checkpoint for several days, creating lengthy delays at neighboring checkpoint Chonhar in Kherson Oblast. After the checkpoint reopened, the worker said, the average commute time, from his home village of Preobrazhenka to the plant – around 15 kilometers – became an hour-and-a-half. Additional staff and an unwritten agreement with border officers on the Ukrainian side have seen the checkpoint process become faster and simpler, he said.

But, he added, on the Russian-occupied territory, the situation was more difficult. “In 2014, Russia set up stations at the checkpoints, and those who had worked there from the beginning and remembered us – we had no problems with them. But the younger ones… they don’t give us too much trouble, but their checks last a long time. They ask us personal questions. They think they’re in charge and they’re allowed to do anything. ”

The next hour would show a meager handful of tourists trickling across the border.

Testing times

On Dec. 31, 2014, less than a year after Russia illegally annexed Crimea, hundreds of Ukrainians working at Armyansk’s titanium factory lost their jobs temporarily.

A new law requiring all “foreign nationals” to have a “patent” – a working permit for employment in Crimea – went into effect.

The worker said colleagues were told they would be rehired once they obtained the patent. But the process took three months.

In February 2015, workers from Preobrazhenka, 526 kilometers southeast of Kyiv, blocked the Vadym railway leading to the plant, obstructing the delivery of raw materials.

“We blockaded it during the day and through the night, and the next morning things were sorted to our advantage,” the worker said.

At the end of March, the factory began drawing up documents for the patents, but the process involved a series of tests – from language and history knowledge to medical exams.

Those who finished school before Sept. 1, 1991, (i.e. those who had finished school before the breakup of the Soviet Union) were exempt from sitting the Russian language and knowledge tests.

The 60-year-old worker was among them.

He said that while didn’t have to take the test, he learned about the questions asked from others.

He said the younger workers applying for the patent reported that the exam included questions on the Battle of Kulikovo, and asked them to identify Russia’s old coat of arms amid similar looking symbols from former Soviet countries.

“They had questions that we were supposed to know, even the though the Russians themselves didn’t,” he said.

“We thought they just wanted to get rid of the workers, so there would be fewer of us.

“But of course with the internet, (the workers) found the answers to the questions and… those who wanted to work there passed the exam.”

Only option

Another worker is among 20 laborers who travel from Pershokostyantynivka – a town of 1,500 people, 522 kilometers southeast of Kyiv – to Armyansk. He felt it was his only option.

“Judge me or don’t judge me that I work in the occupied territory. Maybe it’s wrong that I work there,” Pavel said. “But there’s no work here and I have a big family. I have six kids. The oldest is 13, the youngest is 18 months.”

Those who had the luxury of leaving have already gone.

This worker makes 15,000 rubles (around Hr 5,960 or $231) a month, but that’s before exchange-related losses and the patent eat away at his paycheck.

The patent costs workers 3,000 rubles (around Hr 1,192 or $46.29) a month, but he said they don’t pay taxes as a tradeoff.

“It’d be better if we did pay taxes though, because we’d get taxed about 2,000 rubles, but the patent is 3,000 rubles,” he said.

Taking a toll

More than half of the Kherson Oblast workers that have remained at the factory live in Preobrazhenka. Today a bus picks the workers up from the village and transports them to the Kalanchak checkpoint, which they cross by foot, before another bus transports them from the other side of the border to the factory.

The head of Preobrazhenka village council, Andriy Suchok, said he has seen the toll that working at the plant has taken on its Ukrainian employees.

“Even at the beginning of this year there were 100 (workers) from Preobrazhenka. Now there’s 62. People are leaving themselves,” he said.

During the September 2015 blockade, activists dumped a slab of concrete and an anti-tank hedgehog on the railway line leading to the factory, effectively putting a stop to the delivery of raw materials to the plant.

Suchok said that in addition to the difficulties of sourcing raw materials through Russia, the factory was experiencing water shortages, which had resulted in a decline in production. He believes that as a result, the factory is currently working at 25 percent of its capacity.

Another worker confirmed that the factory wasn’t working at its full capacity these days.

Some days it worked at 75 percent of its capacity, he said, others at 25 percent.

Like most of the workers, he refused to be identified in the story for fear of losing his job. For many, the plant feels like their only option.

“If we had work here (in Kherson Oblast), we wouldn’t need the plant,” a worker said.

After a day’s work, the workers’ bus pulls into Preobrazhenka, a touch after six in the evening. The workers file out and, after some quick goodbyes, head home.

Tomorrow, they’ll do it all again.