Ukraine’s grain producers could be close to eliminating their biggest pain point.

After years of complaining that the state railway monopoly Ukrzaliznytsia lacks capacity to transport the up to 60 million tons of grain produced yearly in Ukraine, grain producers have been offered a possible solution.

At the Government-Business Dialogue, a forum where President Petro Poroshenko met with business representatives on Oct. 31 in Kyiv, the president said that Ukrzaliznytsia had one month to draft a bill that would allow it to attract private equity to finance new cargo trains.

This was a response to grain producers’ demands to allow private cargo companies onto the railway freight market to pick up the slack left by the state company.

For Ukrzaliznytsia, that would be a tectonic shift — no private companies have ever been allowed to exploit Ukraine’s railway network.

The president’s offer was a compromise: no private cargo trains, but private equity to finance new trains. However, Ukrzaliznytsia isn’t subordinated to the president, so it’s up to the Cabinet of Ministers to follow the instruction — or ignore it.

Many agree that changes in Ukrzaliznytsia are overdue.

“The services provided by Ukrzaliznytsia do not satisfy either goods suppliers or passengers,” says Infrastructure Minister Volodymyr Omelyan.

He estimates that over 90 percent of the rail company’s assets are obsolete, with cargo train depreciation reaching 98 percent.

Grain producers are the worst affected by this, often having to wait weeks to transport their produce. Smaller producers complain the most, saying the railway company prioritizes the industry giants who can load a full, 54-wagon train.

In turn, Ukrzaliznytsia says having a monopoly on cargo transportation is the only way for the state company to stay afloat — and compensate it for subsidizing passenger train services.

Wanted: trains

The grain producers’ complaints boil down to this: Ukrzaliznytsia doesn’t have enough locomotives to meet the demand for cargo transportation, and even when a train finally arrives, it’s a wreck.

Mykola Gorbachev, head of the Ukrainian Grain Association, told the Kyiv Post that out of a full 54-wagon cargo train, at least half of the wagons are either broken or dirty.

Ukraine exports around 40 million tons of grain a year, and has around 1,000 grain elevators. But only around 5–6 percent of elevators can fully load a 54-wagon cargo train. These grain facilities are prioritized, because loading there is the most time efficient, as trains only have to make one stop to load up.

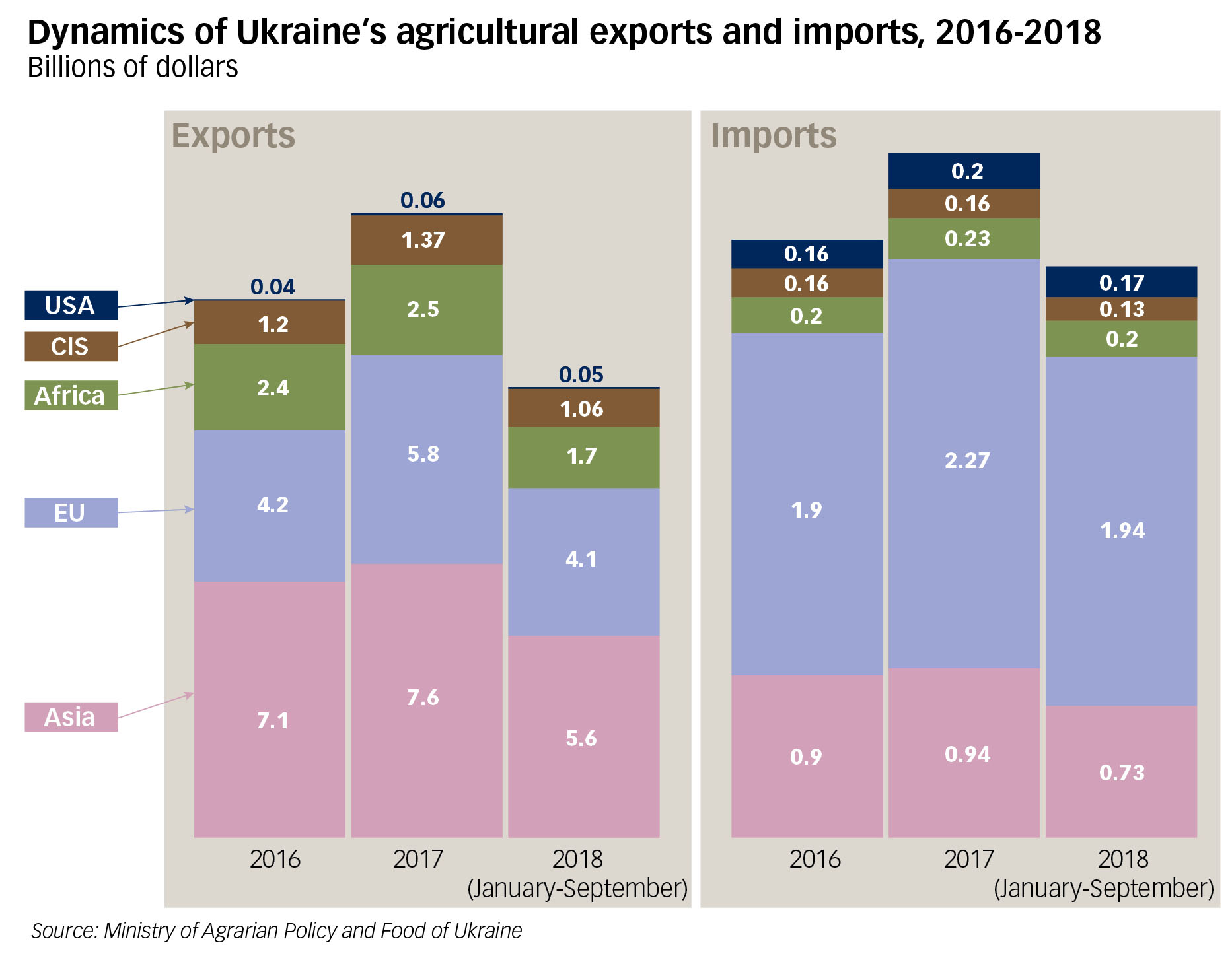

Since 2016, Ukrainian agricultural exports have been slowly switching towards the European Union market, even though Asian countries are still leading as consumers of Ukraine’s agricultural products with a 42.6 percent share in 2017. However, the EU is responsible for nearly half of Ukrainian imports.

As Gorbachev points out, the other 95 percent of Ukraine’s elevators are spread around the country, can’t fill up the whole train, and are therefore neglected by Ukrzaliznytsia.

Ukrzaliznytsia also has a locomotive shortage: According to the company’s equipment inventory, it has 1,758 cargo locomotives. But only 945 of them are in use — the rest are broken or under repair.

The state-owned monopoly has ordered 30 diesel locomotives from General Electric, the U.S.-based conglomerate. Half of them have been delivered, while the rest are expected in 2019.

But the consensus among experts that the required number of locomotives needed to cover the shortage is at least ten times that amount — their estimates range from 300 to 500 units.

And it doesn’t help that no one knows exactly how the state company allocates cargo trains to the businesses that need them. The state enterprise contracts forwarding agents — private intermediaries who work on a commission basis, who decide on the number of cargo wagons that are sent to the grain elevators. This factor lends itself to potential corruption.

According to Gorbachev, the role of the forwarding agents is crucial, as whether the small elevators get grain wagons and a locomotive to go with them depends solely on the allocator. Large agrarian companies have more sway on the agent’s decision, while the smaller farmers have to fight for whatever is left.

Oleksiy Vadatursky, CEO of agrarian giant Nibulon, defended Ukrzaliznytsia’s focus on large grain elevators, but acknowledged the general inefficiency in grain loading and transporting is harmful for the industry.

“When I’m asked if there are enough wagons in Ukraine, I say ‘yes,’ but when I’m asked are they used efficiently, I definitely say ‘no,’” Vadatursky said.

He added that the practice of using intermediary agents to allocate the cargo wagons is causing chaos in the industry, with wagons often left standing empty, waiting for the highest bidder.

The average delay when Ukrzaliznytsia transports grain from small elevators is approximately two weeks, with some grain storage facilities having to wait nearly a month for their grain to be shipped, according to Gorbachev. And because the grain is not transported on time, some the subsequent harvest is lost as well.

“We gathered only 70 percent of the corn (this year), because there was nowhere to store it,” says Gorbachev.

Ukrzaliznytsia is having trouble with upgrading its cargo fleet such as these cargo wagons that are stationed in Odesa Sea Port on July 28, 2018. The country’s grain exporters are complaining about major delays due to the lack of locomotives and wagons and the necessary infrastructure. (Volodymyr Petrov)

The situation in turn creates uncertainty on the grain market, with contract obligations frequently not met. As a result, investors either look elsewhere — deciding not to deal with small Ukrainian grain exporters — or they demand lower prices as compensation for taking on the risk of unforeseen problems occurring with Ukrainian companies.

Failed efforts

An initial push to address the railway problems came last year, when bill No. 7316 was registered in parliament. The draft law “On railway transport of Ukraine” was supposed to replace outdated railway regulations adopted back in 1995. According to the proposed legislation, the government would have been able to lease railroads to private companies for up to four years.

The infrastructure ministry and the parliament’s Transport Committee supported the aforementioned bill. However, the law was rejected at first hearing, drawing only 202 votes, with 226 needed for it to pass.

Volodymyr Shulmeister, the former deputy infrastructure minister, was part of the team that worked on the bill during its early stages. He reckons that overall, the bill would have been a huge step forward, introducing market-based pricing for passengers, and opening up the railroad to private cargo companies.

Infrastructure Minister Omelyan also expressed regret that the law wasn’t adopted, adding that several members of parliament are working with the ministry to revive the initiative.

Future prospects

The situation will most likely change eventually, with the push for this coming from Europe: Ukraine’s Association Agreement with the European Union, which came into force in September 2017, envisions the de-monopolization of the railroad over a seven-year period.

The European Bank of Reconstruction and Development said on Nov. 9 it would give Ukrzaliznytsia a loan of up to $150 million for the state enterprise to purchase around 6,500 new gondola-type wagons via an open tender.

However, Omelyan predicts that if Ukrzaliznytsia continues to renovate its trains at the same pace, it won’t be until 2030 that the wagon fleet is fully renewed.