STARYI SAMBIR, Ukraine – Maksym Kozytskyy’s business changes with the wind. When it blows strongly, his wind farms in western Ukraine produce more energy and earn him more money.

His first wind farm, in the town of Staryi Sambir in Lviv Oblast, which has four wind turbines with a total generating capacity of 13.2 megawatts, produces enough energy to supply the town and neighboring region of 80,000 citizens.

And using the earnings from the feed-in tariff – introduced in Ukraine to accelerate investment in renewable energy technologies – Kozytskyy and his company Eco-Optima LLC plan to build another three wind farms in the Carpathian Mountains.

Power of the wind

In Staryi Sambir, a town of 6,500 citizens located some 30 kilometers from Ukraine’s border with Poland and 640 kilometers west of Kyiv, the four wind turbines are visible from almost every street. The three-bladed turbines, standing on a low hill to the east of the town, are each 119 meters high. The farm produces 32 million kilowatt-hours of electricity per year. Close up, the swishing of the turbine blades is clearly audible, but from the town nothing can be heard.

While today the farm operates under full computer control, setting up the farm required significant effort. Eco-Optima spent three years on preparations before the first two turbines started to spin in 2015.

Over that time, two suppliers went bankrupt. Even to transport the 56-meter-long turbine blades, the company had to broaden narrow roads of western Ukraine, cutting down trees, moving fences, and taking down power lines.

“This was the first project, and we made a lot of mistakes,” Kozytskyy said. “Now it’s much easier.”

Remote control

Roman Voloshchak, a 79-year-old power engineer, oversees the operation of the city’s four wind turbines. He retired from a life-long career in energy sector construction to work in the renewable energy business.

Voloshchak operates the turbines remotely from his computer at home. In addition, the system can be switched off from Lviv or Melitopol. “There is no need for me to sit there (inside a turbine),” Voloshchak said.

On a typical day in mid-February, the turbines’ blades are spinning at speeds of up to 13 meters per second, enough to convert wind energy into a good amount of electrical power. The blades start spinning when wind speeds reach three meters per second, and can operate at wind speeds of up to 25 meters per second. If wind speeds are faster than that, the turbines automatically shut down to prevent them being damaged.

The turning blades capture wind energy, driving generators on top of the turbine towers. The electricity then goes through a transformer located on the farm, which then feeds it into the electricity grid. Sensors control the direction of the turbines, keeping them facing the wind to capture the most energy.

Inside each turbine, a small room is equipped with a control panel, climbing harnesses and helmets, and a ladder to top of the turbine tower. There is also an elevator, which works only when the blades are stopped, Voloshchak said.

At first the locals were wary of the wind farm, coming up with various unfounded objections. For instance, they said that water would dry out in their wells because the turbines would suck up all of the wind, or that the blades would cut bees in half, Kozytskyy recalled. Today those fears are gone, and the wind farm is a popular place for taking wedding and school prom photographs, he said.

“There’s a local legend that we take people (to the top of the turbine) by elevator for Hr 50,” Kozytskyy jokes.

Family business

For Kozytskyy, producing energy is a family business. His father has gas and oil drilling companies in western Ukraine and also works for Eco-Optima, while his brother has a well drilling company.

Besides Kozytskyy’s own investment, the wind farm got a credit from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. The second part of the farm, which will have six turbines, will be located on another hill near Staryi Sambir, and will start operating within the next few years.

Plus, the company develops a solar direction. Eco-Optima owns two solar power plants in western Ukraine – in Sambir in Lviv Oblast and Bohorodchany in Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast.

Kozytskyy said that building of the solar plant takes less time and effort than the wind farm. “To me, solar projects look like Lego for kids,” Kozytskyy said of installing solar panels.

Feed-in tariff

To boost the development of the renewable energy sources, the government introduced a renewable energy feed-in tariff in 2009. The tariff is linked to the exchange rate and is to be cut every year until 2030. With this strategy, the government hopes to encourage the building of renewable power plants and increase the share of renewables in the energy mix to up to 20 percent.

Kozytskyy was one of those who has been encouraged – he said the entire business happened because of the introduction of the tariff. “There were probably some of the best conditions in Europe (to start a business),” he said, looking back on the launch of Eco-Optima.

The law became even more relevant following the start of Russia’s war on Ukraine in the Donbas, and Ukraine’s slashing its dependence on Russian gas.

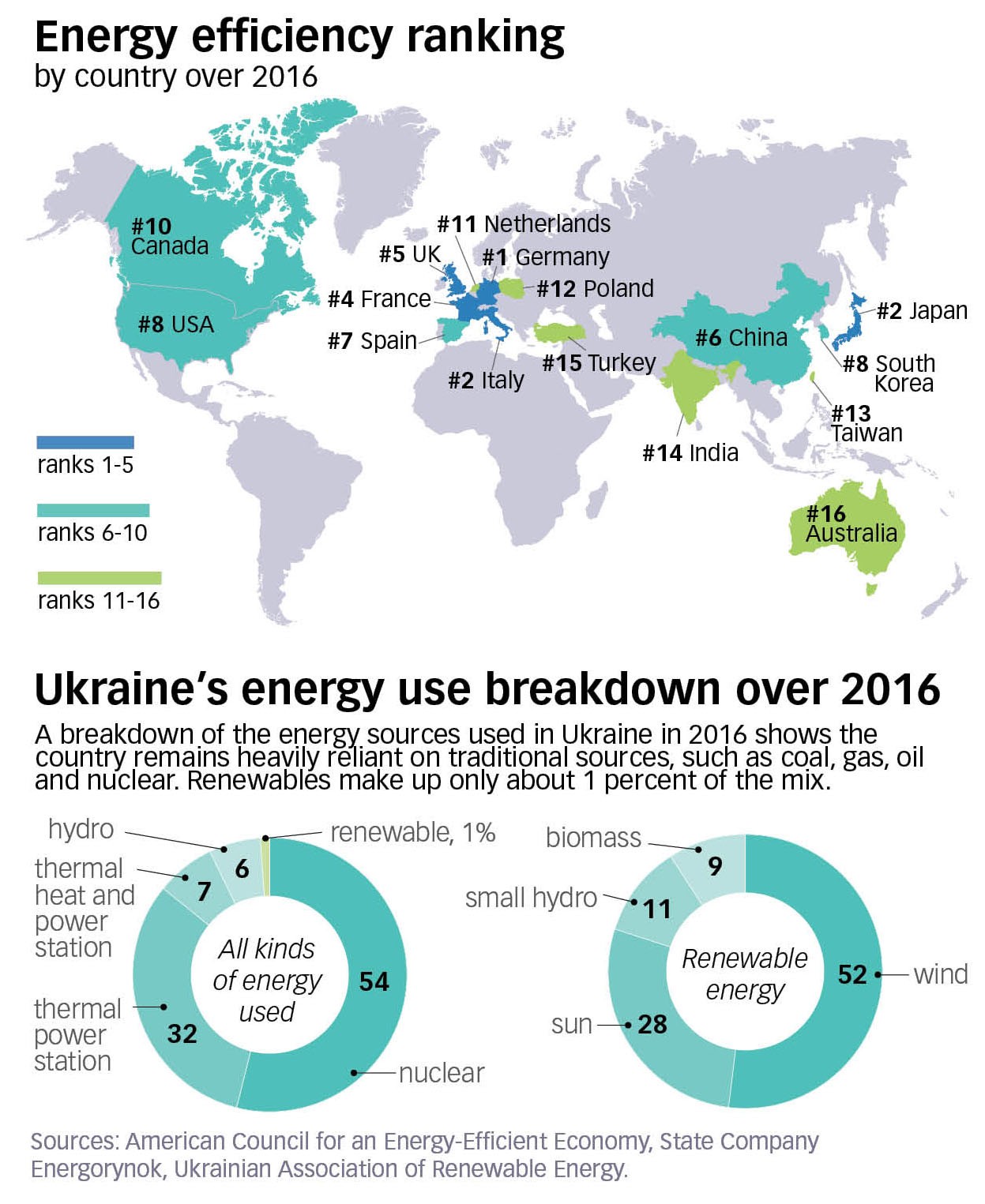

However, the share of renewable energy produced in 2016 was only 1.25 percent, according to the Ukrainian Association of Renewable Energy. “It’s just ridiculous,” Kozytskyy said, pointing to countries like Germany, where the share of renewable energy in total power generation has already reached 30 percent.

To hit the 20-percent target for renewable energy generation, more investment is needed, but time for the launch of new projects like Kozytskyy’s is running out.

Kozytskyy said that in order to make a profit under the feed-in tariff, a power plant would have to be up and running, and feeding power into the national grid, by 2019. After that, as the feed-in tariff is cut back, the project simply won’t earn enough money to pay back credits from the EBRD or other investment banks.

Kozytskyy plans to launch two more wind farms, in Skole and Sokal districts of Lviv Oblast, and complete the second part of the farm in Staryi Sambir within the next two years.

“If the feed-in tariff is discontinued, the money will go away and no one will invest here,” Kozytskyy said. In total, his company has invested 75 million euros in solar and wind power plants.

“If there hadn’t been a feed-in tariff, we wouldn’t have invested in them.”