ZOLOCHIV, Ukraine — Zolochiv Mayor Igor Hrynkiv points proudly at the 19th-century basalt cobblestones in the small but tidy historic center of his western Ukrainian city.

Construction workers in 2012 discovered them in this Lviv Oblast city of 24,000 people, 450 kilometers southwest of Kyiv. They were laid when Zolochiv was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, but were covered over by four layers of poor-quality asphalt laid after the city fell under Soviet rule.

Just as the street, now a pedestrian walkway, Hrynkiv hopes to restore the entire city, a prosperous trade center in early 20th century, by attracting both Ukrainian and foreign investors.

“This city has strong foundations,” Hrynkiv says. “It would be good to revive them.”

Hrynkiv, 47, Zolochiv’s tall and energetic mayor since 2010, says the city offers investors a good location and a potentially big selling point: Zero tolerance for corruption.

Located between two western Ukrainian provincial capitals, Lviv and Ternopil and a two-hour drive from the Polish border, Zolochiv, badly needs new businesses and more jobs so that it can support itself with local taxes.

Otherwise, it will remain dependent on subsidies from the central government in Kyiv and the regional authorities in Lviv, Hrynkiv says.

Such aid often comes with political strings attached.

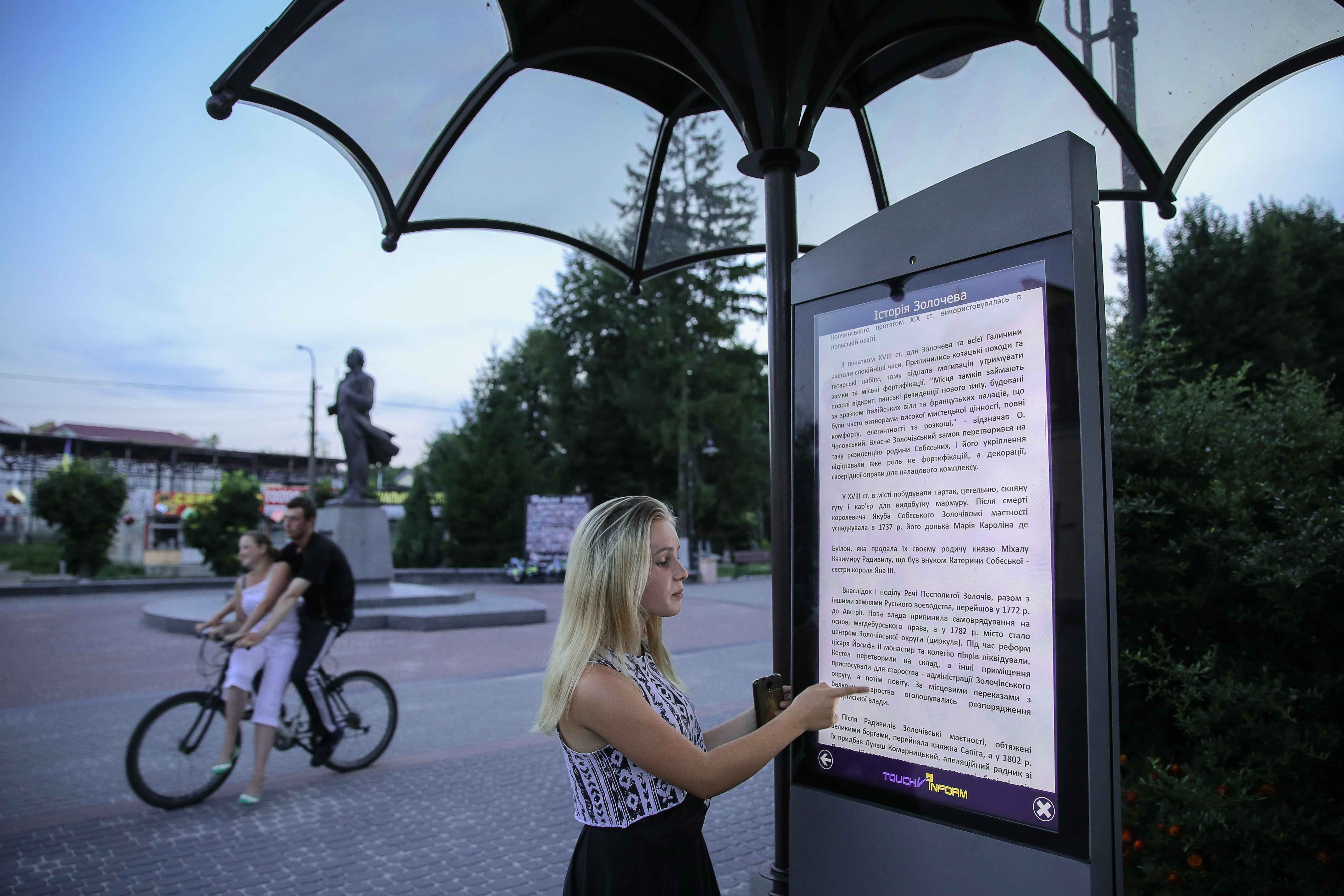

Zolochiv Mayor Igor Grynkiv shows recent renovations of the city on Aug. 2. The city still needs $1 million to finish the reconstruction of its central square. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Less financing

In 2015 and 2016, Lviv Oblast Council declared Zolochiv the most environmentally friendly of the oblast’s district centers. It is also the first in Ukraine to stop using natural gas as fuel for its municipal heating system, making the switch to waste wood in 2013.

It did so while getting less money from the state and oblast — $1.4 million in 2015 down to $115,000 in 2016. In the first six months of 2017, Zolochiv has received only about $5,000 from the higher governments.

Consequently, the city is poorer and can’t find the money in its annual budget which barely exceeds $1 million to finish the reconstruction of its main square.

“There is the Regional Development Foundation of Lviv Oblast, which has an annual budget of some $5.7 million, and would be good if that money had been divided equally between all the communities,” Hrynkiv says. “But the reality is that some communities get much more than others.”

Political dilemma

Hrynkiv is politically independent but with leanings to the Samopomich Party of Lviv Mayor Andriy Sadovy, who is interested in challenging President Petro Poroshenko’s re-election bid in 2019.

The mayor says his political stance could be one reason why Zolochiv started getting less government support.

Hrynkiv says he regrets that earlier he was a member of the Party of Regions, led by former President Viktor Yanukovych, who fled the country on Feb. 22, 2014, amid the EuroMaidan Revolution.

From Yanukovych to Poroshenko, he says corruption remains a big problem.

“The Inspectorate of the State Architectural and Building Regulator demands bribes from those who want to start and finish construction work. And these bribes are higher than were in the times of the previous regime,” Hrynkiv says.

No jobs

Olga Popadiuk, 48, poses for a photo in the city center, which is glimmering in the sun after a summer rain shower. She says Zolochiv has become much nicer in recent years, with restored streets, new benches and new street lighting.

But, lacking jobs, many residents have left for Kyiv, Lviv, Russia or neighboring Poland.

“Look what we have here: second-hand stores, pharmacies, small food shops and bars,” says Popadiuk, an unemployed agricultural science graduate. “We used to have a big radio plant and a meat plant.”

Oleksandr Smolinsky, 27, standing with his wife at the city square, agrees. “The square is aesthetically nice, but it doesn’t give anything to residents apart from a place to walk,” he said.

Smolinsky, who worked for several years as a builder in Moscow, is now a recruiter, finding jobs for locals in Poland.

Foreign investment

Indeed, there are lots of ads for work in Poland or bus tours to Russia in the city. Hrynkiv fears that more people will leave for work in Poland now that Ukraine has a visa-free travel with European countries of the Schengen Zone.

In 2011, Hrynkiv spent six months in difficult talks to attract a company with foreign investment to Zolochiv. The company, Elektrokontakt Ukraine, a daughter company of Germany’s Elektrokontakt GmbH, in the end brought more than 1,000 jobs to the city.

Elektrokontakt Ukraine set up production at the former military radio plant. The new plant produces cables for big international carmakers, including BMW, Opel, Audi and Porsche.

The average salary at the plant is about $330 per month, while the average salary in the city is about $200 per month in the private sector and only about $115 for state sector workers.

Still, Volodymyr Yurtsan, the director of Elektrokontakt Ukraine, says it is hard to retain staff since they can still earn more working in neighboring Poland.

Common cause

Yurtsan says his company paid for the large flower pots planted with evergreen Thuja trees that now decorate the city center.

Hrynkiv says he often calls on local businesses to donate money. The numerous new benches in the city, for example, were paid for with joint donations from local enterprises.

The mayor also often calls on city residents to organize the cleaning of local parks. “Anything we can do with our hands, we try to do this way,” Hrynkiv says.

In 1995, Zolochiv pioneered the launch in Ukraine of housing cooperatives for owners of apartments in multi-story buildings.

In 2015, the city won a three-year grant from the European Union and the United Nations Development Program to restore roofs of local residential buildings.

Hrynkiv says city authorities decided to start restoration work only if the residents of apartment buildings pay 25 percent of the cost of the work (foreign donors pay 50 percent and city pays the remaining 25 percent.)

“This allowed us to include more houses in this project, and made people more responsible,” he says.

Reform doubts

But while the central government is touting its decentralization, which grants more powers and responsibilities to local authorities in merged communities, Zolochiv is in no hurry to participate in this initiative.

Hrynkiv, who is a lawyer and an accountant by education, says if Zolochiv creates a merger with several nearby villages, the city will gain nothing but more debts. And while it will retain the lion’s share of the taxes raised from local businesses, the city will also be forced to take over the financing of local schools and hospitals — something Kyiv does now.

The mayor says that all the successful merged communities are surviving because of the Ministry of the Regional Development, which subsidizes them.

Hrynkiv says that city started receiving significant revenues to its budget when it was allowed to retain excise tax duties collected locally from fuel sales at gas stations, and from the sale of cigarettes and alcohol. However, he says the excise tax rules are likely to be changed soon, taking away this source of funding.

“Nobody is in a hurry to make local communities strong,” Hrynkiv says.

Setting an example

Meanwhile Zolochiv’s authorities are trying hard to attract foreign donors and investors.

Igor Muryn, the mayor’s adviser on international issues, said the city is now applying for several projects together worth $11.5 million.

One project involves finding investors for the construction of a waste incineration plant.

And Hrynkiv says that the German town of Schoningen, Zolochiv’s sister city, is ready to help Zolochiv apply for a project to install solar panels on building roofs.

The mayor regularly travels abroad to learn about city development and court investors. He says the city has two land plots, of eight and 11 hectares, which he is offering to investors as sites to build new factories.

Belgium Ambassador to Ukraine Luc Jacobs has traveled to Zolochiv twice in recent months and says the city is a good example for other Ukrainian municipalities to follow.

“I’m already in touch with experts in Belgium to see how we could provide ideas, good practices for this,” Jacobs told the Kyiv Post.

Hrynkiv, however, also looks to Zolochiv’s past for inspiration about the future.

“We look at the old photos of Zolochiv. Such nice buildings, such elegantly dressed people. What’s wrong with us? Why can’t we be like them?” he asks.

The old cemetery in Zolochiv has graves of the once implacable enemies, including Polish, Ukrainian, Soviet soldiers and German prisoners of war. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Greatness and horrors of Zolochiv’s history

ZOLOCHIV, Ukraine — Some 100 years ago, Zolochiv was a cozy merchant city in the Austro-Hungarian Empire with Ukrainian, Polish and Jewish communities peacefully coexisting for centuries. The city enjoyed self-governance by the Magdeburg rights since 1523.

Two world wars changed all that.

Now Zolochiv’s Polish community consists of some 300 residents, who are united by the 18th century Roman Catholic Church of the Ascension. The Jewish community no longer exists.

The old cemetery offers a compelling illustration of the city’s tragic history.

The angels decorating the old Polish graves stand next to the more modern and modest Ukrainian tombstones.

The graves of the Polish officers killed in between 1918 and the 1920s are located next to the tombs of the 22 Sich Riflemen — a Ukrainian unit of the Austro-Hungarian army during World War I that participated in fighting for Ukraine to become an independent state.

The cemetery also has the graves of Soviet soldiers, soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army and graves of German prisoners of war.

There is also a common grave of 611 Ukrainian and Polish civilians who were killed by the NKVD Soviet secret police in 1939–1941.