When Yevgen Nikiforov started taking photographs of Ukrainian Soviet-era mosaics at the end of 2013, he didn’t know that more than three years later it would grow into a 255-page book titled “Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet mosaics.”

The book, published by Osnovy in May, includes photographs of 200 mosaics throughout Ukraine, including Russian-occupied Crimea and parts of war-torn Donbas. They are divided into seven chapters: people, labor and industrialization, history and ideology, sport and leisure, science and space, folk and national motifs, small architectural forms and mosaic ensembles.

“I thought it was important to bring people’s attention to the fact that they’re surrounded by art,” Nikiforov said. “The art that is hidden by modern renovations, new tacky buildings and uncontrolled advertisements.”

The project gained new meaning in April 2015, when the government passed laws that ban communist symbols. The laws spread to include art objects. Many mosaics have since been destroyed, painted over or covered.

“Back then it became clear to me that I had to hurry up because in a short space of time part of the works I shot and the ones I was about to shoot would be destroyed or obstructed.”

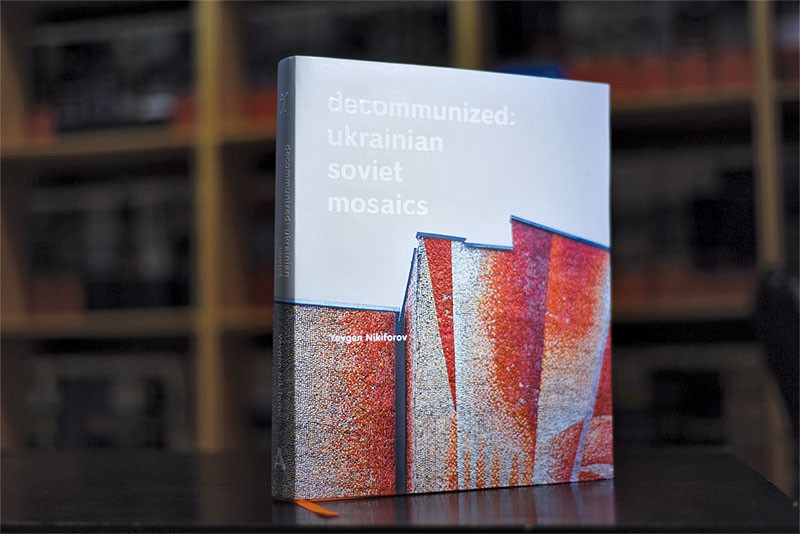

The book cover of “Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics.”

Kyiv-born Nikiforov, who used to be a fashion photographer and worked in China, started documentary photography in 2013 when the EuroMaidan Revolution had just started.

“I was visiting Ukraine on vacation. But I couldn’t leave the country, so I carried on my career in Ukraine and took photographs of the events that unfolded in Kyiv,” Nikiforov says.

Around the same time, he was asked by Osnovy publishing house to shoot mosaics for their previous book “The Art of the Ukrainian Sixties,” a task that inspire “Decommunized: Ukrainian soviet mosaics.”

“I was inspired by the artists’ life stories, how they created these works and what difficulties they faced in the process,” he says.

Nikiforov says he had to start from scratch to find Soviet mosaics, as there isn’t a universal archive. He consulted periodicals and spoke to ethnographers and locals in different towns. “Eventually I had something like a tree which took me from big cities to smaller towns and villages,” he says.

He traveled to Crimea, but Donbas was a harder catch. While he was planning his trip, Russian militants found out about Nikiforov’s project and offered their help for $300.

“I did not want to cooperate with local militants and some uncertain people and it was still dangerous. So I found three people via social media who agreed to photograph three mosaics in Donetsk and Krasnodon,” Nikiforov says.

Personal preferences

By the time the book was sent to print, Nikiforov had traveled around 120 places in Ukraine. Now the number is 170, as he still cannot leave his hobby behind. He also has a separate decommunization project that is almost done.

“Decommunization is still in process and maybe when it will be over that will be my stop in it.”

Nikiforov says that his favorite piece is located in Ostrovskiy museum in Shepetivka. He is also impressed by the work inside the Molodaya Gvardiya museum in Krasnodon, Donbas.

“As to Kyiv, I really like the mosaics on Peremohy Avenue. It’s a complex of six mosaics and the two in the middle, which are the oldest among them, are my favorite,” he shares.

The hardest one to shoot, Nikiforov says, was the one in Mariupol airport. The airport serves as a military base for Ukrainian soldiers fighting against Kremlin-backed separatists. Other places had limited access: in Pripyat (where the Chornobyl nuclear disaster took place in 1986), he had to persuade tour guides to show him where the local mosaics are because they are not a part of the tourist routes.

Sadness

With sadness, Nikiforov talks about the decommunization law. Although he agrees with the law, the removal of monuments “should have been carried out with greater attention and care. The mass-produced works aside, like the hundreds and thousands of similar-looking (Vladimir) Lenins in every town and village, there are some quite unique things that should have been transported to a territory that could eventually become a museum of totalitarian art.”

The museum would serve an educational purpose, he says. “It would help people understand why the communist regime was bad and what crimes it was guilty of. So that we don’t see anything like that in the future.”

“Decommunized: Ukrainian Soviet mosaics” can be purchased online on http://osnovypublishing.com or at all major local bookstores for Hr 1,200.