On the June 27 eve of Ukrainian Constitution Day, Deputy Ukrainian Prime Minister Pavlo Rozenko sat down at his desk and started up his computer.

But instead of the familiar booting up routine, his computer suddenly restarted. Then his monitor showed a black screen with a warning that there were problems with his operating system.

“At first, I couldn’t understand what was going on,” Rozenko told the Kyiv Post.

But when Rozenko found out that all of his colleagues’ computers had been affected in the same way, he realized that they had been infected with a virus.

They turned off their computers, but the virus had already spread through government computer systems, encrypting information on them, and not just in Rozenko’s office.

His computer was only one of some 12,500 machines across Ukraine attacked by the NotPetya virus, which initially appeared to be ransomware, malware that encrypts vital data and demands money for the key to decrypt it, in what is now reckoned to be the biggest cyberattack in country’s history.

The virus’ name derives from the Petya virus, which has been active since spring 2016, but NotPetya uses stronger encryption, which enabled it to seize the systems of high-profile companies, including Danish shipping giant Maersk, U.S. pharmaceutical company Merck and numerous Ukrainian government offices.

How it started

Shortly after noon on June 27, the virus started to strike Windows-run computers used by Ukrainian telecom companies, banks, postal services, big retailers, and government bodies.

Among those were state-owned savings bank Oschadbank, private bank Ukrgazbank, energy companies Kyivenergo and Ukrenergo, national telecommunications operator Ukrtelecom, mobile carrier Lifecell, postal companies Ukrposhta and Nova Poshta, Kyiv Boryspil International Airport, DIY chain Epicenter, petrol retailers, and several media companies, including Channel 24 and the Korrespondent news website.

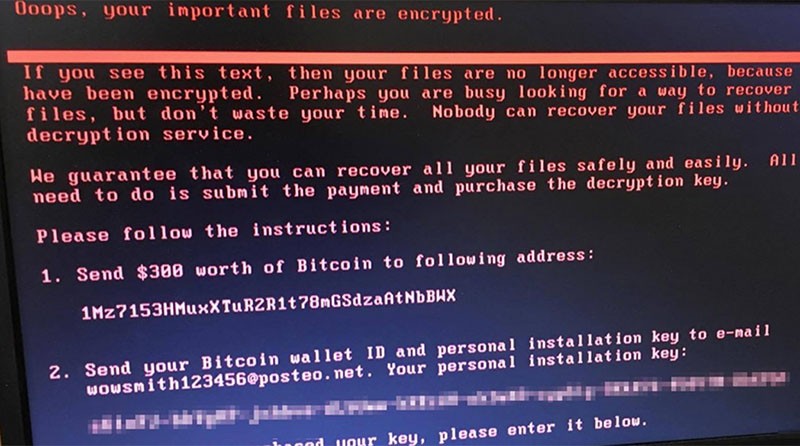

The virus took over the computers, encrypted data and demanded a ransom of $300 in bitcoins, a digital currency used to carry out untraceable transactions. Some people even paid to get their data back — the bitcoin wallet used in the attacks in Ukraine received 45 transactions.

Ransomware notices started to appear on computer screens in Ukraine after noon on June 27. (Courtesy)

On June 27, U.S. software company Microsoft released a statement saying that it now has evidence that the ransomware was initially spread via Ukrainian-produced tax accounting software called Medoc. The software is widely used by the Ukrainian government. Hackers are thought to have hid the NotPetya virus in a software update the company provided to its many customers at around 10:30 a. m. local time.

Initially thought to be ransomware, NotPetya in fact wipes computers outright, destroying all records from targeted systems.

According to Kaspersky, a Russian antivirus developer, there’s currently no solution to help decipher files after the latest ransomware attacks. According to them, the ransomware uses “a standard, solid encryption scheme,” and the data can’t be accessed unless the hackers have made a mistake in their code.

Russia suspected

The creators of the virus are yet to be identified.

Costin Raiu, the director of Global Research & Analysis Team at Kaspersky Lab, said they don’t see “any strong indication” that could point to particular authors.

“Our analysis indicates the main purpose of the attack was not financial gain, as is usually the case with ransomware attacks, but widespread destruction,” Raiu said in written comments provided to the Kyiv Post.

While Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council Oleksandr Turchynov spoke about the “Russian traces” in the attack, and Minister of Transport Volodymyr Omelyan said that it was apt that the word “virus” ends in “Rus,” cyber experts have been more cautious about ascribing blame.

Microsoft said in a statement that while the first infections started in Ukraine, the virus was also recorded in another 64 countries, including Belgium, Brazil, Germany, Russia, and the United States. Microsoft Ukraine would not elaborate on the situation now, saying only that its engineers are investigating the case.

However, the vast majority of the infections occurred in Ukraine.

Pirate software

Oleksandr Korneiko, the president of the Ukrainian Academy of Cyber Security, said Ukraine suffered the most because of negligence.

“There’s no proof that it won’t happen again,” Korneiko said. “The biggest problem is that (people) don’t use licensed Windows software and don’t update their operating systems.”

Licensed Windows software, which costs about $150 per computer, appears to be too expensive for many private and government offices in Ukraine.

Valentyn Nalyvaichenko, the former head of Ukraine’s SBU state security service, said he made sure the security service had licensed Windows software back in 2014. “But I’m sure the government and even the Ministry of Defense haven’t cleaned the (pirate software) up,” he told the Kyiv Post.

Nalyvaichenko added that up to 90 percent of government officials also risk catching such viruses, as they use their office computers for browsing social networks.

“It would also be good if the SBU and the police, instead of raiding IT companies, attracted more Ukrainian developers to urgent cybersecurity projects,” Nalyvaichenko said.

Rozenko said while he uses licensed software on his laptop at home, he doesn’t know whether his office computer had licensed Windows software.

Latest attack

This isn’t the first time Ukraine has been under cyberattack. In December 2015, power company Prykarpattyaoblenergo suffered a major attack that led to blackouts across western Ukraine.

About 230,000 Ukrainians were plunged into darkness for six hours after hackers inserted malware into control systems of part of the oblast grid.

Ukraine blamed Russia for the attack, and the malware used, BlackEnergy, has its origins in Russia, according to experts. However, there is no definitive link between the cyberattack and the Russian government, according to U.S. officials.

The malware was reportedly delivered via spear phishing emails with malicious Microsoft Office attachments.

People try to enter a closed branch of Oschadbank on June 27 in Kyiv. Oschadbank had to close its operations on that day due to the virus attack. (AFP)

A year after that, another attack hit an electricity transmission facility outside Kyiv. In a report by tech magazine Wired, cybersecurity firms that have since analyzed the attack said it was executed by a “highly sophisticated, adaptable piece of malware” now known as “CrashOverride,” a program coded to be “an automated, grid-killing weapon.”

And while nobody really knows how to deal with the computer virus, companies in Ukraine and across the world are still grappling with the effects of a major new ransomware cyberattack that struck their computer systems.

Ukrainian delivery service Nova Poshta were still affected on June 29.

“Our offices, the website and application programming interface works now,” Tetyana Potapova, a spokesperson for Nova Poshta told the Kyiv Post. “But some computers are not working yet. And we’re also trying to ensure that our clients can use non-cash payments again.”

The client services of Kyivenergo, which provides Ukraine’s capital with electricity and heat energy, were still limited on June 29 due to the virus attack.

Who’s in charge?

On June 29, Ukraine’s SBU security service issued a statement that it, together with the U.S. FBI, the UK’s NCA, Europol and other leading cyber security companies and specialists, are currently investigating the spread of the NotPetya virus, trying to identify those behind the attack.

At the same time, Ukrainian authorities together with global tech company Cisco are working on software to recover blocked computers.

Cisco spokesperson Yulia Shvedova told the Kyiv Post that such attacks are common, and that they will continue to happen as hackers develop more and more sophisticated techniques.

“Even if you were lucky this time, you should take all possible precautions so as not to be the victim next time,” Shvedova said.

Neil Walsh, head of the UN Global Program on Cybercrime, called the current virus more sophisticated than the WannaCry ransomware virus, which wreaked havoc worldwide less than two months ago. Reportedly the work of North Korean hackers, WannaCry affected computers that had failed to install one of the latest updates to Windows.

Among the major victims of that ransomware were the British National Health System, the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, and Japanese carmaker Nissan.

Walsh said it still was unclear whether Ukraine was the main target of the NotPetya virus. Cyber security experts were also working to identify the attackers, he said.

“This could be anything from a kid sitting in his basement… to a nation state,” he said.

Prevention methods

While the malware is sophisticated, prevention steps are rather simple.

Andrey Kosovay, head of IT infrastructure at Ciklum, says users simply have to ensure their operating systems are kept up-to-date. They should also have antivirus software installed, and also regularly update it.

Kosovay warns people should not open software and links sent or developed by suspicious sources.

Raiu of Kaspersky also says the companies should install the latest Windows patches, strengthen their security with packages such as Microsoft EMET (Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit), and update all third party software.

Meanwhile, as the world’s authorities and cyber security specialists look for ways to recover the data on affected computers, the computer of Deputy Prime Minister Rozenko remains unusable. He and the members of his department have had no option but to bring their own laptops to work.