The purchase of a $60,000 apartment in Kyiv by U.S. citizen Michael Arrington doesn’t at first sound like a real estate deal that would merit global attention.

But when you add in the facts that Arrington is the founder of the popular U.S. tech news website TechCrunch, and that he purchased the property with a cryptocurrency, using blockchain technology, from across the Atlantic, via the internet, the significance of the deal becomes apparent.

The media entrepreneur struck the historic deal without the use of banks or real estate brokers: it was arranged through a smartphone application called Propy that runs on blockchain — a public ledger of all transactions done through cryptocurrencies, a technique used to secure the integrity of recorded data.

Blockchain is a relatively new technology, initially designed to verify the ownership of assets and exchange digital information without the need for intermediaries. The same technology is now being tested as a potentially reliable method to record transactions of physical assets like land and real estate.

The technology makes details of the transaction available to the public, with an online ledger being updated on thousands of computers at the same time, while the buyer and seller remain anonymous. Anyone who wanted to tamper with past transaction information would have to alter all of the thousands of copies of the blockchain data — a virtual impossibility.

Still being tested by the real estate market, blockchain deals in this field are slowly gaining popularity due to their transparency and security. The United States, for example, has already had its first home sales via blockchain in Miami, California, and Texas. In the United Arab Emirates, a real estate developer has started to accept cryptocurrency as payment as well.

Arrington’s purchase of a Ukrainian apartment, however, was the first transatlantic electronic agreement involving real estate. Arrington paid 212.5 units of a cryptocurrency called Ethereum (RTH), the equivalent of about $60,000 when the agreement took place, and used smart contracts to sign all necessary documents online.

The arrangement still involved intermediaries — the Ukrainian law firm Juscutum and U.S. firm Velton Zegelman — to make sure the deal complied with U.S. and Ukrainian law.

Juscutum managing partner Artem Afian told the Kyiv Post that after his company completed the agreement, lots of people in Ukraine had started asking him about the legal possibility of buying property using cryptocurrency.

“It means people who sell and who buy property are looking for new ways to do it,” Afian said.

Blockchain skeptics

But Eduard Brazos, head of the committee of information systems and analytics at Ukraine’s Association of Real Estate Experts, is skeptical. The real estate agent agrees that blockchain could bring some changes to the industry, but doubts that Ukraine will embrace them.

“Ukraine’s real estate industry is super-regulated,” Brazos told the Kyiv Post. “Our (Justice Ministry) still requires physical documents signed by buyers or their representatives in the presence of an attorney.”

Brazos does not believe that Arrington’s purchase is actually secure, since he views it as a simple barter exchange, meaning that after the buyer and seller agreed they would exchange digital money and the apartment, they both signed gift certificates to secure the transaction, without anything else.

And he sees no point in using blockchain while Ukraine’s laws still require lawyers to be involved in real estate transactions, and do not recognize cryptocurrency transactions.

“I don’t see why anybody needs to use it anyway, except just to show off,” Brazos said.

Unreliable documents

Nevertheless, for countries like Ukraine, which rely on paper records to register land and other real estate rights, blockchain does make sense as a way to avoid corruption.

Traditional real estate systems ensure the integrity of information by placing it in the hands of state entities they trust. In the United States, courthouses and city halls are charged with the safekeeping of land deeds. The United Kingdom entrusts this responsibility to the government-controlled Land Registry. In Ukraine, it is the responsibility of the Ministry of Justice.

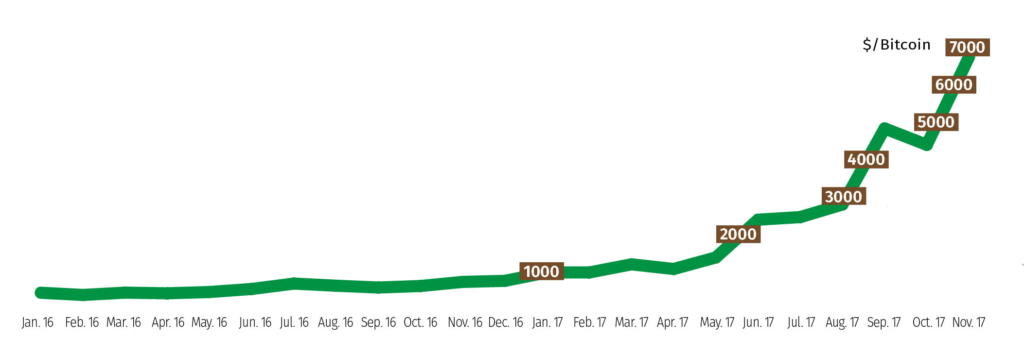

The trust people put in cryptocurrencies has pushed up the value of most popular virtual money a lot over the last year. The popular virtual currency Bitcoin, for example, was valued at $7,269 as of Nov. 3, while it was at only about $750 at the beginning of 2017.

However, any government representative or lawyer who can access the register on behalf of their client, if corrupt, can alter the content of paper records such as deeds and claims. Considering that Ukraine is 131st out of 176 states in the world’s ranking of the least corrupt countries, according to Transparency International, the country’s registries may not be secure.

Apart from corruption, the process of conveying and confirming property ownership on paper is considered to be costly, opaque, bureaucratic, and highly vulnerable to fraud.

Acting Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food Maksym Martyniuk agrees.

“For the average person, (blockchain) means a better level of control over their property, because if you only have a piece of paper to verify your right to a piece of land, that can be a little worrying,” Martyniuk told the Kyiv Post on Oct. 21.

“It’s more reassuring when all your property is recorded in an electronic database.”

Blockchain on the rise?

Work to put such registries in Ukraine in a blockchain format is already going on.

In cooperation with blockchain company BitFury, Ukraine transitioned the registration of land ownership records into the company’s blockchain system in October. State authorities are sure that the property registry information is now secure and transparent.

The system also allows the use of smart contracts — automated online documents that work algorithmically, allowing the transfer of money or property only if all the conditions of a contract are fulfilled. This can automate some bureaucratic functions and help reduce the number of staff needed to carry out the process.

But even though real estate agent Brazos believes that blockchain will indeed make the register more secure, future success still depends on how the Ukrainian authorities implement the technology.

“If you give savages the best tools, you might not achieve anything,” Brazos said. “Give the most accurate tool to officials and they could spoil everything.”

Private lawyer Ruslan Chernolutsky agreed with Brazos. He thinks that while blockchain does secure information once it’s in a registry, it still doesn’t ensure that all the information is correctly entered initially. Some people deliberately enter false data into registries for purposes of deception, Chernolutsky said.

“Obviously, blockchain is powerless here. It’s just a tool,” he said.

The Kyiv Post’s IT coverage is sponsored by Ciklum. The content is independent of the donors.