The idea that the murder of journalist Pavel Sheremet in Kyiv could be linked to Belarus has been floated for years.

But the Jan. 4 publication of an alleged audio recording implicating the Belarusian KGB in the murder added more evidence and credibility to this version.

Belarusian-born Sheremet was blown up in his car in central Kyiv on July 20, 2016. The Belarusian government has denied involvement in the murders of Sheremet and other opponents of Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko.

Sheremet exposed the crimes of Lukashenko’s regime, including political assassinations, and was preparing a new book on the subject before he was killed.

Apart from the recording, the key to the murder case could be found in Sheremet’s complicated relationship with his fellow Belarusian Sergei Korotkikh, a fighter in Ukraine’s Azov volunteer regiment.

On the night preceding Sheremet’s murder, Korotkikh and other Azov fighters met near Sheremet’s house. Korotkikh’s violent background as a neo-Nazi has attracted attention since the assassination.

Read also: Police have conflicts of interest in Sheremet investigation

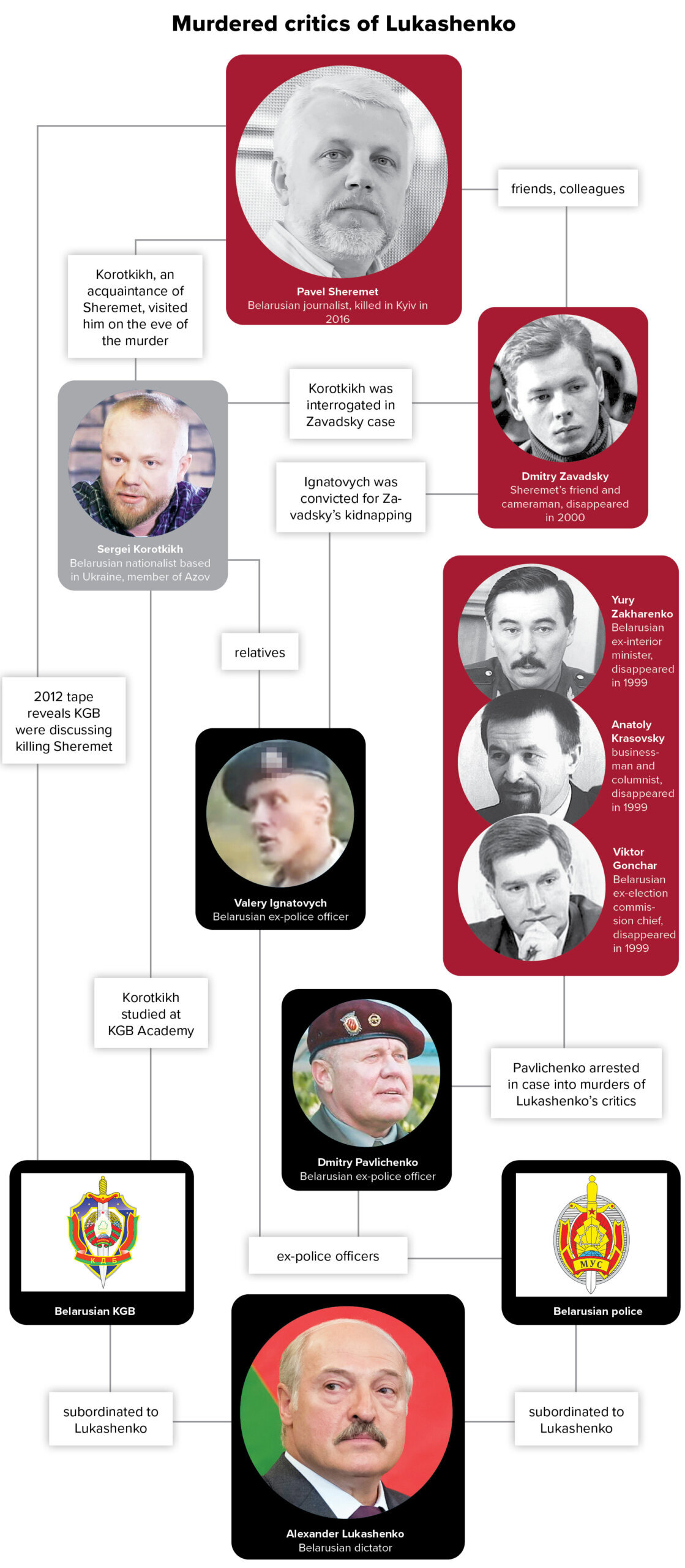

Korotkikh is a friend and relative of former Belarusian police officer Valery Ignatovych, who has been convicted of kidnapping Sheremet’s cameraman and friend Dmitry Zavadsky, who disappeared in 2000 and is believed to be dead.

Korotkikh denied having anything to do with the murders of Zavadsky and Sheremet and insisted that Sheremet was a friend of his.

Three official suspects in the Sheremet case — Andriy Antonenko, Yulia Kuzmenko and Yana Dugar — were arrested in 2019. Critics of the investigation see the evidence against them as very weak and are calling for the release of Antonenko, who has been in custody for over a year, and Kuzmenko, who is under house arrest.

The suspects’ defense attorneys argued that the new Belarusian evidence refutes the official version since there is no evidence of any links between their clients and Belarus. Ukrainian police disagree and are proceeding with the case.

Several critics of Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko were killed in 1999-2000. Belarusian journalist Pavel Sheremet exposed their assassinations and was friends with one of those killed, Dmitry Zavadsky. Sergei Korotkikh, a nationalist with ties to intelligence services, who has previously attacked Lukashenko’s opponents, met with Sheremet on the eve of his murder in Kyiv on July 20, 2016. (Kyiv Post)

KGB recording

The alleged KGB recording was published by EUobserver, a Brussels-based English-language publication, and the Belarusian People’s Tribunal, an opposition group run by exiled Belarusian police officer Igor Makar.

The leaked tape was allegedly recorded on April 11, 2012, with a secret device in the Minsk office of Vadym Zaitsev, who was then head of the KGB, the Belarusian state security committee.

“We should take care of Sheremet, who is a massive pain in the ass,” Zaitsev said, according to the 2012 recording. “We’ll plant (a bomb) and so on and this fucking rat will be taken down in fucking pieces — legs in one direction, arms in the other direction. If everything (looks like) natural causes, it won’t get into people’s minds the same way.”

In the recording, people alleged to be Zaitsev and other KGB officials also discuss murdering Lukashenko’s other opponents — Oleg Alkayev, Vladimir Borodai and Vyacheslav Dudkin. Zaitsev said Lukashenko had authorized the planned assassinations.

Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko meets Viktor Sheiman, his current office manager and former head of the security council, on Jan. 11, 2021. Sheiman was investigated in the case into political assassinations in Belarus, but Lukashenko stopped the investigation. (president.gov.by)

Sheremet and Lukashenko

The roots of what happened in Kyiv on July 20, 2016 may be found in the period when Sheremet and his friend Zavadsky lived in Minsk.

Before starting to work with Sheremet, Zavadsky was Lukashenko’s personal cameraman from 1994 to 1997.

In 1996, Sheremet became the head of Russian television channel ORT’s Belarusian bureau. He was highly critical of Lukashenko’s nascent dictatorship.

In 1997 Sheremet and Zavadsky were jailed for several months by the Belarusian government for crossing the Belarusian-Lithuanian border after they produced a television report on smuggling between the two countries. This incident caused a major conflict between Belarus and Russia, with Russian President Boris Yeltsin explicitly demanding the journalists’ release.

At the time, the conflict caused great PR damage to Lukashenko’s plans to lead a united Russian-Belarusian state that eventually failed to materialize.

Sheremet wrote a highly critical book about Lukashenko called “Accidental President.” In it, he wrote that before Sheremet’s arrest in 1997 Lukashenko said that law enforcers should “put an end” to the journalist. Sheremet also said on March 6, 2000 on ORT that he was prepared for death because of his conflict with Lukashenko.

“Lukashenko is a sick man, and Pavel was his personal enemy,” Dmitry Zavadsky’s wife Svetlana Zavadskaya told the Kyiv Post. “That is why I cannot rule out a Belarusian version.”

Former Belarusian investigator Dmitry Petrushkevych told the Kyiv Post that Lukashenko had reasons to order the murder of Sheremet. The late journalist was a passionate opponent of the dictator.

“When Sheremet gave me a column (on the Belarusian Partisan), his only condition was that I don’t write anything good about Lukashenko,” he added.

Political assassinations in Belarus

In 2000–2002, Sheremet produced two documentaries on political assassinations in Belarus.

Lukashenko’s three main opponents, ex-election commission head Viktor Gonchar, ex-Interior Minister Yury Zakharenko and columnist Anatoly Krasovsky, disappeared in 1999. Sheremet’s friend Zavadsky disappeared in 2000. They are believed to be dead.

In 2000, the Belarusian prosecutor general and KGB chief arrested Dmitry Pavlichenko, a police unit chief and a loyalist of Lukashenko, in the case into the murders of the opposition leaders and Zavadsky.

They also sought to arrest Viktor Sheiman, then head of Lukashenko’s security council, and then Interior Minister Yury Sivakov in the case.

However, Lukashenko fired the officials who initiated the arrest, released Pavlichenko and appointed Sheiman as prosecutor general. The case was buried.

In 2019, a man named Yury Garavsky, who fled Belarus, claimed to be a member of Lukashenko’s death squads in an interview with Deutsche Welle and admitted to participating in the murders of Zakharenko and Gonchar.

In 2006, Sheremet and Alkayev, another alleged target of the Belarusian KGB from the newly leaked recording, published “The Death Squad,” a book about political assassinations in Belarus. The two were working on a new book when Sheremet was murdered in 2016.

“I don’t doubt that employees of the Belarusian KGB are implicated in Sheremet’s murder,” Alkayev told the Insider, a Russian news site. “He was an irritating factor for Belarus because he and I were working on an update of the book, and (Sheremet) was the editor, publisher and my friend. We were planning to re-publish the previous book and publish a new one.”

In 1999, Alkayev was the head of a Minsk detention facility. He was among the first people who exposed the political assassinations in Belarus and fled to Germany.

Then Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko (R) meets Belarusian-born Sergei Korotkikh, a member of Ukraine’s Azov regiment, on Dec. 5, 2014. Korotkikh visited journalist Pavel Sheremet on the eve of his murder on July 20, 2016. (UNIAN)

Sergei Korotkikh

The Belarusian version of Sheremet’s murder is also linked to his relationship with a fellow Belarusian, Sergei Korotkikh, who at the time of the murder also lived in Ukraine.

Korotkikh is a Belarusian nationalist with links to neo-Nazi groups. In the 1990s, he studied in the Belarusian KGB academy but dropped out. He is a friend and relative of former Belarusian police officer Valery Ignatovych, who has been convicted for kidnapping and murdering Sheremet’s cameraman and friend Zavadsky in 2000.

Late on July 19, 2016, on the eve of Sheremet’s murder, six Azov members, including Korotkikh and Azov leader Andriy Biletsky, met with Sheremet near his house. The Azov members later said that they were going to participate in a coal miners’ rally the next day, and sought Sheremet’s advice about the event’s media strategy.

Hours later, unknown people attached a bomb to Sheremet’s car, parked near the place of the meeting. In the morning, when Sheremet was driving to work, the bomb exploded and killed him.

A law enforcement source who was involved in the investigation told the Kyiv Post he did not believe the Azov members’ explanation that they had only discussed the miners’ rally. He said that it would not have made sense for them to go there at such a late hour instead of just calling him on the phone.

The source spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak to the press.

Conflict with Korotkikh?

Oleh Odnorozhenko, a former deputy commander of Azov, told the Kyiv Post that Sheremet tried to find out whether Korotkikh had something to do with Zavadsky’s murder. Odnorozhenko has fled to Poland due to his conflict with Azov’s leadership.

“Sheremet and Korotkikh spoke several times in Ukraine,” Odnorozhenko said. “Korotkikh was trying to convince him that he had changed his (neo-Nazi and anti-opposition) views. They allegedly came to an understanding. Korotkikh was trying to persuade him that he had nothing to do with Zavadsky’s murder.”

Odnorozhenko also said that two days before the murder, Sheremet had gone to the Azov headquarters at the Atek factory building in Kyiv.

“(Sheremet) met Korotkikh and other people and had a major quarrel,” he said. “This was heard by several people. They heard them argue loudly. They didn’t understand what the essence of the argument was but they said it had something to do with Belarus. As far as I understand, Sheremet could have received information that Korotkikh is implicated in the Zavadsky case.”

The law enforcement source who was involved in the Sheremet case said that Korotkikh had a potential motive to go after Sheremet — Sheremet’s investigations into Zavadsky’s murder and into the Belarus death squads of which Korotkikh’s relative Ignatovych was allegedly a member. The Azov fighters, including Korotkikh, could also be potential suspects because they had the military experience and weapons to carry out the attack, the source added.

However, the Ukrainian investigation never seriously considered Azov members as possible suspects.

“There is zero reaction from law enforcement agencies,” Odnorozhenko added. “They (Azov) enjoy absolute impunity. That’s why they do whatever they can and whatever they want.”

Korotkikh repeatedly denied involvement in Sheremet’s murder.

Suspects Andriy Antonenko (R), Yana Dugar (C) and Yulia Kuzmenko (L) attend a court hearing on Jan. 12, 2020 in Kyiv in the case into the murder of journalist Pavel Sheremet. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

Years preceding the murder

Sheremet and Korotkikh got acquainted after the latter arrived in Ukraine and joined Azov in 2014.

In January 2015 Sheremet’s site Belarusian Partisan published his interview with Korotkikh, while Ukrainska Pravda ran Sheremet’s column about him.

Sheremet said that Korotkikh was a “hero” to Ukrainians due to his participation in the war with Russia.

“Some of my comrades and colleagues started to justify him and wrote that his past is not as important as his present and that, through services rendered to democratic Ukraine, he had atoned for the sins of his youth against the Belarusian people,” Sheremet wrote in his column, mentioning Korotkikh’s links to Belarusian neo-Nazis and his assaults on Belarusian opposition activists in 1999 and 2013. “I don’t believe so. All these high-profile kidnapping cases don’t have a statute of limitations and no military feats in Ukraine or elsewhere will prevent us, Belarusians, from bringing serious accusations and going after those suspected of these crimes.”

He said, however, that he had talked to Korotkikh and found his explanations convincing and the accusations against him unfounded.

Sheremet’s interest in Korotkikh and Azov continued in the months preceding his murder.

For several months before the murder, Sheremet and an Ukrainska Pravda journalist were investigating a conflict between Azov and volunteer Svitlana Zvarych. At the time, Azov accused Zvarych of embezzling part of the money intended as donations for Azov fighters.

Meanwhile, a Belarusian activist who spoke on the condition of anonymity told the Kyiv Post that four days before the murder, Sheremet had asked him whether he had changed his negative opinion of Korotkikh. The nationalist said he had not.

Azov came up in one of Sheremet’s last columns. In a July 17, 2016 op-ed, three days before the murder, Sheremet wrote about the arrest of a gang of bank-robbing Azov fighters by the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU).

Sheremet praised then-SBU Chief Vasyl Hrytsak and Azov leader Biletsky for avoiding a conflict over the arrest, but warned that Biletsky needs to be “watched” because of his “Nazi youth.”

Korotkikh himself and several sources interviewed by the Kyiv Post described the relationship between him and Sheremet as good.

Others said the relationship was strange, being a supposed friendship between a Belarusian opposition liberal and a pro-Lukashenko neo-Nazi.

“I cannot call this a friendship because Sheremet suspected him of killing his cameraman (Zavadsky),” Odnorozhenko from Azov told the Kyiv Post. “Maybe Sheremet played a game trying to get some information out of him. He was a very professional journalist.”

In a 2015 interview, Sheremet asked Korotkikh about his interrogation in Zavadsky’s murder case. Korotkikh denied that he had anything to do with the murder.

According to Odnorozhenko, Sheremet wasn’t satisfied with the answer and asked Korotkikh the same question at some point after the interview.

When Ignatovych was convicted of the murder, many critics didn’t believe his supposed motive to target Zavadsky. Allegedly, Ignatovych took revenge against Zavadsky for exposing him as a fighter in Chechnya.

Zavadsky, who reported from Chechnya, told the press about a Belarusian police officer among the Chechen insurgents. He didn’t identify Ignatovych by name, but described him. Officially, Ignatovych fought on the Russian side.

Sheremet believed that Zavadsky’s murder had not been properly investigated, and that the organizers and some of the perpetrators had avoided responsibility, according to “Accidental President.”

Both Zavadsky’s wife and Sheremet’s colleagues said that Sheremet continued to be interested in Zavadsky’s murder until his death.

Chechen connection

The tragic fate of Zavadsky and Sheremet may be also linked to their work in Chechnya during the insurgency that started in 1999.

Zavadsky, Ignatovych and Sheremet visited Chechnya at the same time – 1999 to 2000. Based on their visits, Sheremet and Zavadsky produced a documentary called “Chechen Diary.” Korotkikh also said in an interview that he had gone to Chechnya at an unidentified time.

Sheremet wrote in his book that the Belarusian authorities could have wondered before Zavadsky’s murder whether information on Belarusian officials’ links to Chechnya would be published in his “Chechen Diary.” The diary was aired on July 10-13, 2000, three days after Zavadsky was kidnapped.

In his book, Sheremet cited media reports that KGB and police officers among Lukashenko’s security guards had trained and fought in Chechnya. Sheremet said that Zavadsky could have meant these officers when he referred to Belarusians fighting in Chechnya, and Leonenko – a suspect in the Zavadsky case – belonged to the same security guard service.

Sheremet also mentioned alleged ties between top Belarusian officials and Chechens in his book on Lukashenko. Specifically, Chechen rebel Salman Raduyev was transported for treatment through Belarus to Germany, Sheremet wrote.

There is speculation that the exposure of Belarusians fighting in Chechnya could have been a motive for the murders of Zavadsky and Sheremet.

Links to intelligence agencies

Korotkikh’s link to Ignatovych is not his only unusual connection. The Azov fighter’s background is full of links to Belarusian and Russian intelligence agencies, although Korotkikh has denied ever acting in their interests.

Korotkikh served in Belarus’ military intelligence in 1992 to 1994. In 1994 Korotkikh enrolled at the Belarusian KGB school but dropped out later.

In the 1990s both Korotkikh and Ignatovych were among the leading members of the Belarusian branch of RNE, a Russian neo-Nazi group. The Belarusian nationalists interviewed by the Kyiv Post argue that RNE was infiltrated by the Belarusian KGB and the Russian FSB.

Petrushkevych told the Kyiv Post that Korotkikh and Ignatovych had a conflict with Gleb Samoylov, head of the branch, and that Korotkikh had also been investigated in the case into Samoylov’s murder on May 8, 2000.

“The whole RNE was a project of Russia’s intelligence agencies and the main version was that Samoylov was killed due to a conflict around Russian funding,” he said. “And Korotkikh was always around where money was available.”

He also said he believes “Korotkikh executes the orders of those who pay him and obviously he has always been linked to Russian intelligence agencies since the RNE period.”

Korotkikh was also accused of working for the Belarusian authorities when he took part in assaults on Belarusian opposition activists in 1999 and 2013.

Korotkikh in Russia

In Russia, Korotkikh was a member of a nationalist group founded by Maxim Gritsai, whose brother is an officer of Russia’s FSB intelligence agency.

In 2004 nationalist Dmitry Rumyantsev and Korotkikh also founded Russia’s National Socialist Society, a neo-Nazi group. In 2011, 13 members of the society were convicted for 27 murders and 50 assaults in 2008.

Israeli film director Vladi Antonevich believes that the unprecedented wave of murders was instigated by Russian authorities to scare society before the 2008 presidential election.

According to a 2015 investigation by Antonevich, a Tajik and a Dagestani whose murder was filmed in 2007 could have been perpetrated by Korotkikh, Rumyantsev and Korotkikh’s close ally Maxim Martsinkevich.

Martsinkevich committed suicide on Sept. 16, 2020, according to the official version. Russia’s Investigative Committee said that Martsinkevich had admitted to multiple murders, including the murder of the Tajik and the Dagestani, before he committed suicide.

Sheremet’s relations with Korotkikh, a Belarusian with connections to intelligence services, have now come into the spotlight due to the publication of the recording implicating the Belarusian KGB, subordinated to Lukashenko.

The St. Petersburg Forensic Laboratory for Audio and Visual Documents has confirmed the authenticity of the tape, while the ex-officer who published the tape has given testimony to Ukrainian investigators.

“Lukashenko definitely had reasons to order Pavel’s murder,” Belarusian investigator Petrushkevych told the Kyiv Post.