In the span of seven months, President Volodymyr Zelensky has risen from a television comic to the political leader of a large, yet economically lagging, European country at war.

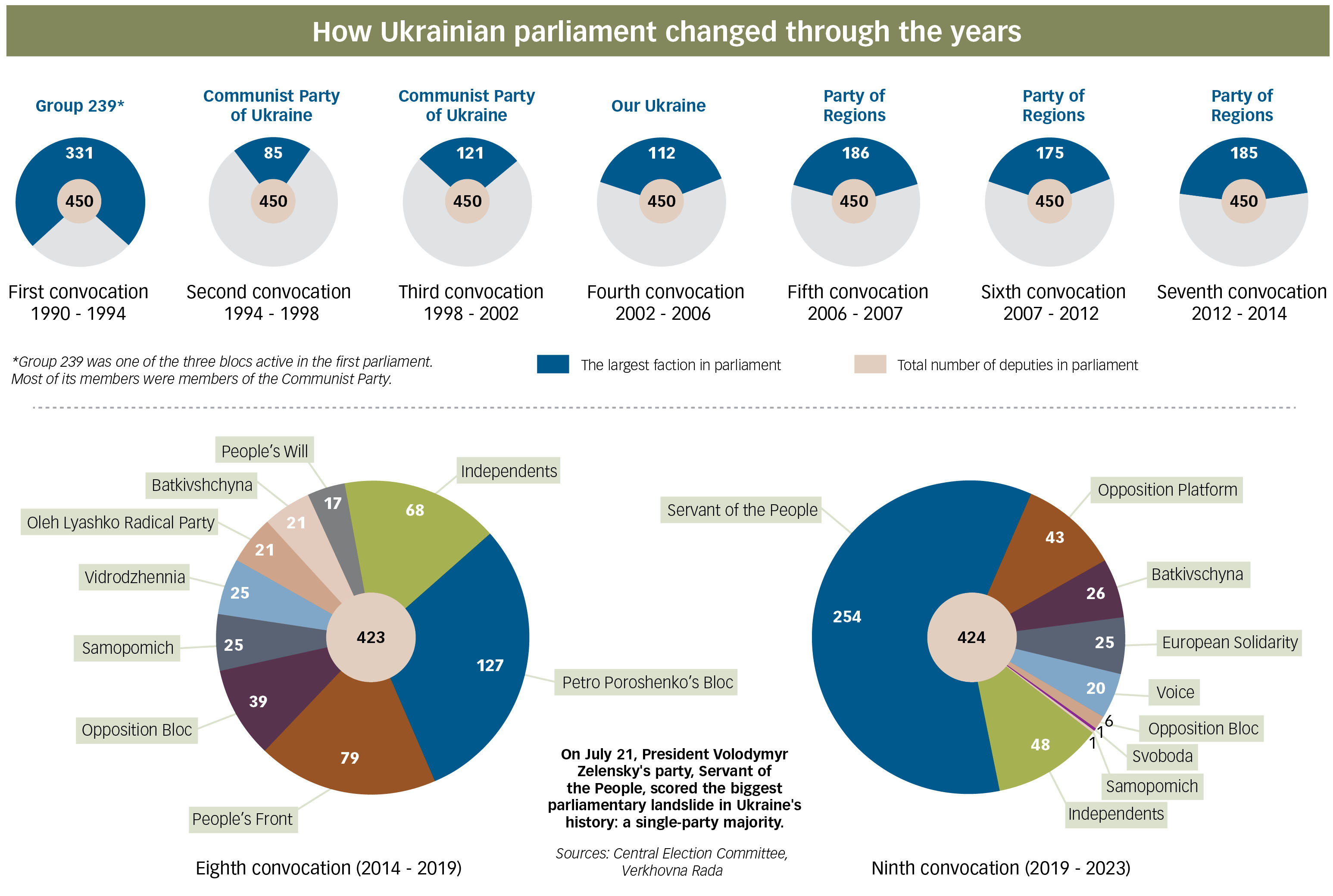

After his landslide victory in the April 21 presidential election, Zelensky scored another big win on July 21 when his party, Servant of the People, took a majority of seats in the new parliament, paving the way for one-party rule.

Voters gave Servant of the People 254 out of 424 seats in the next parliament, handing the political novice Zelensky full power in the legislative and executive branches and a mandate to push for long-overdue reforms.

But Zelensky will have to act fast to deliver on the electoral promises he made to his impatient voters, says sociologist Iryna Bekeshkina from the Democratic Initiatives Foundation.

A recent survey by the foundation showed that, for the first time in four years, the majority of Ukrainians — 60 percent — believed in the success of reforms in Ukraine. Moreover, most Ukrainians place their highest hopes for those changes on the shoulders of Zelensky, the new parliament, and the future government.

“People believe that Zelensky will be the driver of reforms in Ukraine, and they expect quick results from him. People are tired of waiting. They did not elect him to wait for another five years,” Bekeshkina told the Kyiv Post.

An overwhelming majority of Ukrainians consider the fight against corruption to be the top priority. Russia’s war against Ukraine in the Donbas, low salaries, and the high cost of utilities are named among other pressing issues.

Right people

A great deal of Zelensky’s success in improving the economy will come down to the future government he assembles.

The president said he wanted the country’s next prime minister to be an economist without a political past, independent and respected both in Ukraine and the West. Already several names have circulated in Kyiv and the expert community: former Economy Minister Aivaras Abromavicius, Andriy Kobolyev, the CEO of state energy company Naftogaz and Vladyslav Rashkovan, alternate executive director at the International Monetary Fund in Ukraine.

“Any of them would be bulwarks of reform. The West knows these guys very well and trusts them,” Timothy Ash, a London-based strategist focused on emerging markets, told the Kyiv Post in an email.

Zelensky has also yet to name his picks for ministers of foreign affairs and defense, roles that are nominated by the president before going to parliament for approval.

“He has not found the right people yet. The right people will be those who pursue Zelensky’s objectives and have his trust. He needs servants of the people, loyal and capable,” said Balazs Jarabik, a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Zelensky’s intentions to clean up law enforcement agencies, fix the court system, strip lawmakers of immunity from prosecution and adopt a number of anti-corruption laws have sent a positive signal to civil society.

Transparency and anti-corruption watchdogs expressed willingness to cooperate with the president’s office and the new parliament — largely, thanks to respectable reformists like deputy chief of staff Ruslan Ryaboshapka, National Security and Defense Council Secretary Oleksandr Danylyuk and newly-elected lawmaker Anastasia Krasnosilska. Zelensky said he is considering Ryaboshapka for the position of Prosecutor General.

“Zelensky’s team has people who want the same things we do. It will be easier to (carry out reforms) having such allies in the administration,” said Vitaliy Shabunin, chairman of the board of the Anti-Corruption Action Center, at a conference in Kyiv on July 16.

Western partners and investors are closely watching whether Zelensky will able to secure a new IMF aid package and fulfill the commitments he will undertake for it.

Potentially bad choices

So far, Zelensky seems to be heading in the right direction and making good choices, many observers say. But there are also reservations about whether the full power he has been handed could backfire.

Carnegie’s Jarabik says that the consolidation of power does not pose a risk to Ukrainian democracy per se.

“De-facto Ukraine is a presidential republic now by the will of the people. The people gave Zelensky a large mandate to do anything he can to improve the government. What can be more democratic?” he said. “The biggest risk is that he fails.”

However, there are some potentially bad decisions Zelensky could make.

One of them is the lustration law. Zelensky has recently come up with a proposal to ban top officials who served under his predecessor, Petro Poroshenko, from holding government jobs or seats in parliament. That idea drew harsh criticism from the ambassadors of G7 states as “incompatible with democracy.”

Another one is calling for snap local elections before October 2020 to complete the renewal of power on all levels. Although Zelensky has been vague about this plan, civil society watchdogs have spoken out against the idea.

“There are no reasons to call for early local elections. And if Servant of the People decides to amend laws and the Constitution for their political expediency, it will be a warning sign,” Olga Aivazovska, head of Ukrainian election watchdog Opora, told the Kyiv Post.

Additionally, concerns over Zelensky’s ties to oligarch Ihor Kolomoisky have not disappeared since his election campaign. Zelensky made the oligarch’s lawyer his chief of staff and the director of the oligarch’s TV channel one of his top lawmakers.

Zelensky has publicly distanced himself from Kolomoisky and said he would not exert any influence on the case of PrivatBank, the largest lender in Ukraine. It was nationalized in late 2016 from Kolomoisky and his business partner Gennadiy Boholyubov.

Zelensky has pledged to defend the independence of the National Bank of Ukraine, which carried out the nationalization of PrivatBank under the previous administration and is now litigating with Kolomoisky and Boholyubov.

Checks and balances

Zelensky views holding a parliamentary majority as a convenience. It means he will not need to negotiate with anyone, he said in a July 17 video blog.

“It can give us an opportunity to stop the tradition of making arrangements, the tradition of political infighting, selling spots… the politics of compromising. I think we have had enough compromises in 30 years,” he said.

It appears that forming a coalition with any of the three parties that made it into parliament — Poroshenko’s European Solidarity, Yuriy Boyko and Viktor Medvedchuk’s pro-Russian Opposition Platform and Yulia Tymoshenko’s Batkivshchyna — would fundamentally contradict the very ideology of Servant of the People: not to coalesce with old political elites.

However, Zelensky recently invited another celebrity-turned-politician, rock musician Svyatoslav Vakarchuk, to talk about joining forces. Vakarchuk’s new party, Voice, is also comprised of political novices, but scored significantly fewer seats.

“I think coalition with Voice will ensure a big majority and support for difficult reforms,” says Ash. “I don’t think Zelensky can be sure of the loyalty of all (lawmakers) from Servant of the People. The party could well be fractured.”

Jarabik says Zelensky offered Voice a coalition only because he did not expect to win an outright majority but agrees with Ash that keeping such a large parliamentary faction cohesive might be a challenge.

Servant of the People, named after the popular television series in which Zelensky played the role of Ukraine’s president, was cobbled together in two months before the snap parliamentary election that Zelensky hastily called on the day of his inauguration.

It’s a diverse crowd of Zelensky’s campaign managers, prominent experts from civil society, and an eclectic mix of people selected through an open call. None of them have ever been in politics and many of them are practically unknown. But Zelensky’s personal brand is so powerful that it allowed many unknown entities to defeat political heavyweights in the country’s single-member electoral districts.

But Dmytro Razumkov, leader of the Servant of the People, somewhat idealistically disagrees that the party will be unwieldy.

“If the team is aimed at the result and has common goals and tasks, it doesn’t need to be managed: Just go and do it. Everyone simply has to understand their area of competence and responsibility,” he told the Ukrainian news agency Interfax.

Dmytro Razumkov, head of President Volodymyr Zelensky’s Servant of the People party, speaks with the media at the party’s campaign headquarters in Kyiv on July 21, 2019 during Ukraine’s parliamentary election. (Volodymyr Petrov)

Nor does he see any risks in bestowing so much power on one party. He said that Servant of the People wants to give the people tools to control politicians and public officials: making illegal enrichment a crime again, passing a law on presidential impeachment, stripping lawmakers of immunity and punishing them for skipping parliamentary sessions or voting for their absentee colleagues.

“We want to change how the parliament works. So that it becomes professional and not what we see now,” Razumkov said. “We will not influence anti-corruption and law enforcement agencies, as is accepted in Ukrainian politics (today).”

Opora’s Aivazovska says risks are inherent in a one-party majority, but it is difficult to predict the fallout now without seeing Servant of the People lawmakers, who are unknown to the expert community, in action.

Ash suggests that the Ukrainian people and western partners will hold Zelensky and his ruling party accountable.

“Two revolutions show (the Ukrainian people) cannot be taken for granted. If he strays too far from democracy, he risks popular revolt. I would add also that the West and G7 ambassadors will hold his hand,” Ash told the Kyiv Post.

But perhaps it will come down to vanity.

“I want to go down in history as an honest president,” Zelensky said in one of his videos.