When the Russian navy openly attacked and seized three Ukrainian navy vessels and detained their crews, 24 sailors in all, in the Black Sea on Nov. 25, the Kremlin’s new aggression against Ukraine set nerves jangling at home and abroad.

But the Canadian military mission in Ukraine, which is training Ukrainian soldiers at bases around the country, was unfazed, and isn’t going anywhere, the head of Canada’s army says.

According to Lieutenant General Jean-Marc Lanthier, the commander of 40,000-strong Canadian Army, Canada will neither scrap nor scale-back UNIFIER, the extensive Canadian advanced-training mission provided to the Ukrainian military as part of Ottawa’s effort to help defend the country.

“It does not affect negatively, (and) we’re going to proceed with UNIFIER,” the general told the Kyiv Post during an interview on Dec. 4.

“We will continue to provide the assistance to both the (Ukrainian) Armed Forces and the National Guard. In the meantime, we’re looking at how to keep reinforcing the already good capabilities of the Ukrainian security forces.”

Canada’s training mission in Ukraine has been running since 2015, with more than 200 Canadian instructors deployed on six-month rotations at 11 military bases across Ukraine, including the largest army boot camps in Starychi in Lviv Oblast and Desna in Chernihiv Oblast.

The Canadians have been providing advanced courses in those areas the Ukrainian military has the greatest needs: engineering, battlefield medicine, combined arms training, military policing, and also training for new Western-style non-commissioned officers or NCOs.

Lanthier, who was appointed head of the Canadian Army in July 2018, was in Ukraine for the first time to see how effective this mission is now — and also to get to know his counterparts at the top of the Ukrainian military.

Ukraine’s military in turn were looking to make a good impression: the future of the Canadian mission depends on Lanthier’s professional opinion on how well it is working, and how successful the Ukrainian military is in mastering new skills.

Good potential

Lanthier’s visit to Ukraine started with lots of bangs:

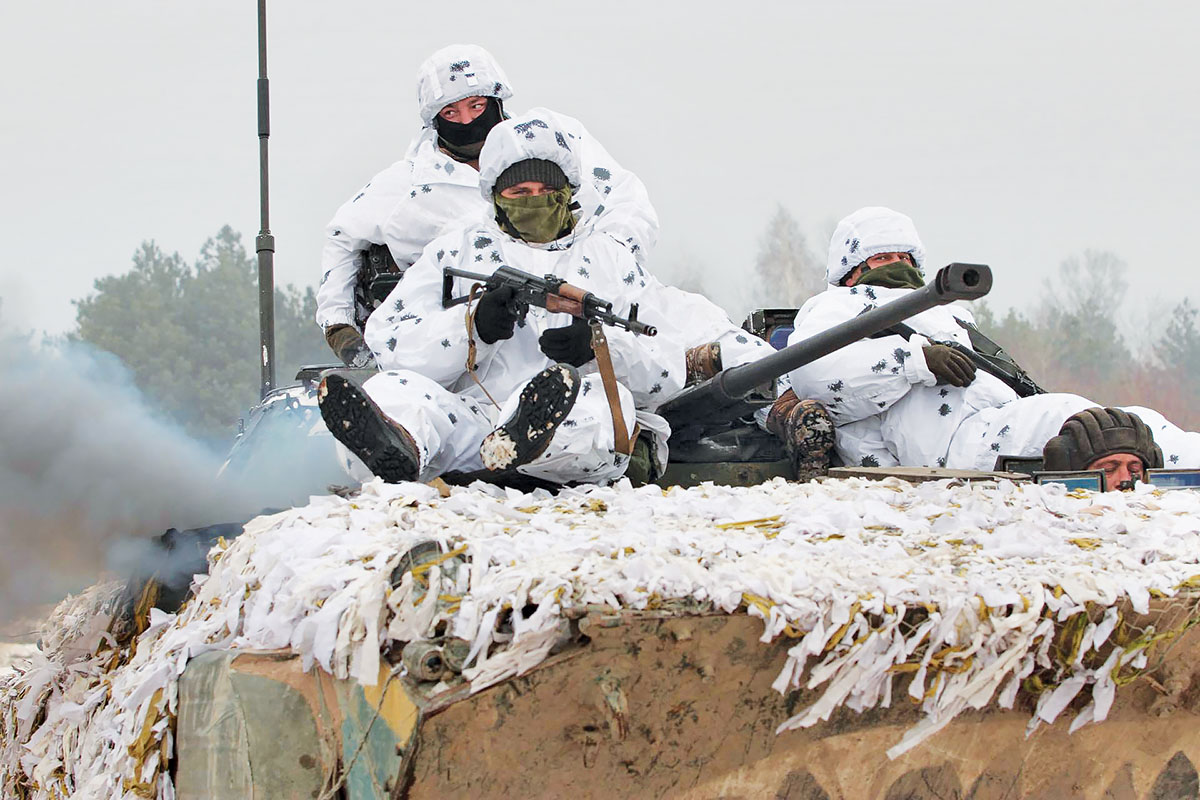

On Dec. 3, he went with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, Defense Minister Stepan Poltorak and Chief of the General Staff Viktor Muzhenko to observe Ukrainian brigade-level, live-fire maneuvers at the Horncharivskiy army firing range in Chernihiv Oblast.

Talking to the Kyiv Post, Lanthier said he was impressed with the cohesiveness and maneuvering capabilities of the Ukrainian troops in combination with armored forces, and also noted their skills in the intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance domain.

He was also impressed by the Ukrainian National Guard forces he inspected early on Dec. 4.

“At the National Guard headquarters, I saw that their leaders have a vision, a firm and realistic plan, it is phased and sequential,” he said. “And I think they’re tapping into one of the greatest potential resources: the development of the non-commissioned officers corps.”

Ukrainian troops ride on top of an infantry fighting vehicle during maneuvers at the Honcharivskiy firing range in Chernihiv Oblast on Dec. 3, 2018. (Defense Ministry of Ukraine)

Lanthier said the UNIFIER mission was helping the Ukrainian military rid itself of the outdated, highly-centralized, and concentrated style of command it inherited from the Soviet era. The Canadian approach gives lower-ranking commanders much more scope to take the initiative on the ground in combat.

“We have an approach at NATO, which is about mission command,” Lanthier said. “We’re working in an active dispersed operation environment, hybrid warfare, information operation. A centralized approach does not work: The single soldier, the NCO, the junior officer, has got to understand the strategic context. He’s got to understand the intent of his commander, and then operate with those broad perimeters.”

The Ukrainian command has understood this Western military approach, and is willing to adopt it, the lieutenant general noted. But at the same time, erasing deeply ingrained military practices will take a lot of time — and also require very strong leadership at the highest level.

“Any cultural change takes a long time,” Lanthier said. “And there’s got to be true desire to change, and patience… It’s a leadership thing. If the highest level do not firmly (embrace) the concepts of mission command and the empowerment of NCOs, then none of this will lead to the potential outcomes.”

Decision made

As of now, up to 10,000 Ukrainian soldiers and officers have attended various UNIFIER courses since 2015, Lanthier said.

Moreover, he added, even though the UNIFIER now provides training at the level of tactical battle groups, with the help of the United States, the training scope could “very soon” be expanded to the brigade level.

On Dec. 3, Ukraine’s ambassador to Canada said he expected Ottawa to prolong the mission in 2019, and Lanthier in turn told the Kyiv Post that given the serious progress UNIFIER has made, he would recommend his government issue a new mandate for next year.

“Recent events show us the situation (regarding Russian aggression against Ukraine) is far from being normalized,” he said.

“So from a military perspective, I certainly see that we’re making a difference, (and) I see a great potential. The National Guard (early on Dec. 4), laid out clearly a plan that transcends the current mission mandate… So my recommendation will certainly be that there’s a great deal we can do, and we can continue to do and continue to evolve to help enhance the capability of (Ukraine’s) security forces.”

As of now, the Canadian Army is participating in 13 missions around the world, including the Multinational Battle Group in Latvia, and a NATO training mission in Iraq, both of which consume a serious amount of resources.

But, the commander says, with the permission of Ottawa, the number of Canadian troops deployed to UNIFIER could be increased from the present 200.

“I can generate more if the government of Canada wants me to do so,” Lanthier said.

“And I’m willing, and I think this is a worthwhile investment — absolutely.”

War laboratory

The UNIFIER mission is not just beneficial to Ukraine’s military: communicating with Ukrainian troops, many of whom have been through the heaviest battles of Russia’s war in the Donbas, the Canadian military also learns a lot from their combat experience, Lanthier noted.

“You’ve got tremendously relevant current experience,” he said.

“It is a symbiosis. We’re able to share our approaches from the systemic, institutional perspective, but we are pulling out a lot of lessons learned: What tactics is our adversary using, how is he using new information operations, hybrid warfare, the use of unmanned aerial vehicles. All of this is also informing our own doctrine and technical procedures.”

Canadian army’s Master Corporal Jodi Bradley of the Operation UNIFIER manages medical supplies at an ambulance post at the International Security and Peacekeeping Center near the village of Starychi in Lviv Oblast on July 20, 2018. (Kostyantyn Chernichkin)

In effect, the well-equipped and high-tech Canadian military is learning what it’s like to fight a superior enemy while being heavily outnumbered and outgunned. Ukrainian soldiers, many of whom fought the battles of 2014–2015 in the Donbas wearing worn-out sneakers and armed only with decades-old Kalashnikov rifles, know all about it.

“We certainly have to be able to operate in a degraded environment,” the Canadian commander said. “You become reliant on technology because it’s there and you have no opposition. But how would you operate when you don’t control the electromagnetic spectrum, when your radios are jammed, and your GPS is (disabled)?”

“One more thing that we’re looking at is how to reintroduce (improvised) methods. I learned to navigate by dead reckoning, not (using) GPS to tell me where I was. So how do you introduce those skills, (such as) the ability to communicate in a secure fashion, but without secure means?”

“We became bigger with technology, and it emboldened us: More cables, more wires, more servers. Well, you can’t move if you’ve got 300 kilometers of fiber optic links — but if you don’t move, artillery will get you. So how do you become agile, mobile, and flexible? Those are the things that we’ve learned from this conflict, and we’re now adapting and modifying our own procedures.”

The whole war in the Donbas is one big laboratory of advanced warfare, Lanthier said, where both sides are trying to outsmart each other in mastering revolutionary battle techniques.

The experiences of the Ukrainian army thus have be closely studied, he added.

Economic security

Lanthier said his first visit to Ukraine had in many ways changed his view of the events in the country.

From Canada it is very easy to forget that Ukraine “is still very much at war,” the lieutenant general said. He admitted that before his arrival he did not fully realize how serious the situation was — even though the majority of the country appears to be in a more or less stable situation.

However, in the wake of Russia’s militarization and monopolization of the Azov Sea and the Kerch Strait, he sees the Kremlin’s ultimate goal as being economic suffocation of Ukraine rather than all-out military invasion.

“I think (the goal) is not to topple Ukraine per se,” Lanthier said. “It’s to prevent Ukraine from looking west. Preventing and taking away the chance of Ukraine to prosper. The human domain of Ukraine, the education, the potential of Ukraine’s people, the richness of the country — some of the most fertile land in the world.”

The Kremlin seeks to turn Ukraine into a poor backward buffer country, endlessly licking incurable wounds, Lanthier believes. To prevent this, Ukraine needs to reinforce its economic security, and particularly its freedom of navigation in the Black and Azov seas — exactly what Russia is trying to strip it of now.

“If you lose access to the sea, of you cannot navigate international waters as per international law, then the economic security of Ukraine is threatened,” Lanthier said.

“You can lose the country without (being defeated in a war), if people lose confidence in their leaders, if their personal situation, economic security, the future of their children, does not look bright.”

“That’s all you need to do to destabilize a country.”