Russia remains Ukraine’s largest export destination ($3.5 billion), its top source of imports ($5.1 billion) and its biggest investor ($1.7 billion) despite the Kremlin’s ongoing war that has killed 10,000 people and dismembered the nation. What are the consequences of trade with the enemy? Is Ukraine still too dependent on its neighbor?

Roman Baskov has several apps on his phone that help him spot Russian goods in Ukrainian stores. The 29-year-old wants to be certain he never buys anything produced in Russia.

“I don’t want to give a single hryvnia to the occupants,” he explains.

He’s not the only Ukrainian to boycott Russian products. But this hasn’t stopped Ukraine and Russia from trading $8.6 billion worth of goods in 2016 – making Russia, by far, the biggest trade partner of Ukraine. The numbers break down into $5.1 billion in imports from Russia – led by oil and petroleum – and $3.6 billion in exports to Russia. Russia was also Ukraine’s largest investor in 2016, with nearly $1.7 billion.

The intensive economic relationship is happening despite Russia’s war that has killed 10,000 people since its start in 2014 and cost Ukraine control of its Crimean peninsula and parts of the eastern Donbas.

Vidsich Civic Movement activists hold posters calling for a boycott of trade with Russia – which has the product code 460 — as other protesters lie on the floor in one of Kyiv supermarkets during a “Russian-made Kills” performance in 2014. (Courtesy of Vidsich)

Trade dropping

Trade has, however, dropped by more than half after both governments imposed selective trade embargoes on each other after Russia’s annexation of Crimea and instigation of the war in eastern Ukraine, both in 2014.

Both nations introduced lists of goods banned for import. However, even banned Russian goods like caviar, meat and fish still find their way onto Ukrainian store shelves.

Trade experts say that one reason for the stubbornly high number is that Russia buys higher-value finished products from Ukraine, while European Union nations favor cheaper raw materials.

‘Doing everything…’

Hanna Hopko, an independent member of Ukraine’s parliament who chairs the parliamentary committee on foreign affairs, told the Kyiv Post she wants Ukraine to become independent from Russia in all ways, sooner rather than later. But she thinks it could take another five years.

However, Hopko said that politicians clamoring for a complete halt to trade have not proposed alternatives and are not ready to take responsbility for such a step.

“They are not ready neither to look for new markets, nor to promote Ukrainian goods,” Hopko said. “Ukraine’s government is doing everything possible.”

Hlib Vyshlinsky, CEO of the Center for Economic Strategy, told the Kyiv Post that the fact that Ukraine keeps trading with Russia while asking West to impose tougher sanctions, is not hypocritical.

Since Ukraine is a victim of Russia’s hybrid war, “it would be the win situation mostly for Russia if Ukraine immediately cut all the economic ties,” Vyshlinsky said. “Because then Ukraine’s economy will suffer and Russia’s message of Ukraine as a failed state to the world will become true.”

A customer examines country-of-origin identifying codes of caviar in a Kyiv supermarket on March 22. Caviar was included in the list of banned Russian goods by the Ukrainian government in 2015. However, experts say Ukrainian businessmen keep buying it from Russia as raw material and repackaging it as “Made in Ukraine.” (Volodymyr Petrov)

‘Soviet heritage’

Ukrainian member of parliament Victoria Voytsitska, who is secretary of the parliamentary committee on fuel, energy and nuclear policy, told the Kyiv Post that many of Ukraine’s nuclear power stations still operate only on Russian-made reactor fuel elements.

Energy expert Andriy Gerus told the Kyiv Post that 70 percent of Ukraine’s nuclear power stations (approximately 9 from 15) can only operate on Russian-made reactor fuel elements.

“This is our Soviet heritage. When all the countries were united, their economies were deeply connected. We’re not the same state anymore, but the economic connection is still very strong,” Voytsitska said.

Voytsitska said Ukraine is trying to diversify its economy and retool its nuclear stations to use U.S.-produced fuel elements, but that this transition requires money and time.

Energy expert Gerus told the Kyiv Post that, over the last two years, Ukraine has diversified its sources of nuclear fuel, buying 30 percent of its fuel in the United States. Soon Ukraine will be importing most of its nuclear fuel from the United States. But that leaves nine out of 15 reactors still dependent on Russian fuel.

Regarding oil, however, Gerus said Ukraine doesn’t have many alternative sources, even though most petroleum imports are from nations other than Russia.

The bulk of Ukraine’s imports from Russia, some $4 billion worth, were the products of heavy industry, including metals, ores and chemical products. On a smaller scale, Ukraine also imported $952 million in clothes, accessories, fabrics and beauty products; $150 million in vehicles; and nearly $20 million in food.

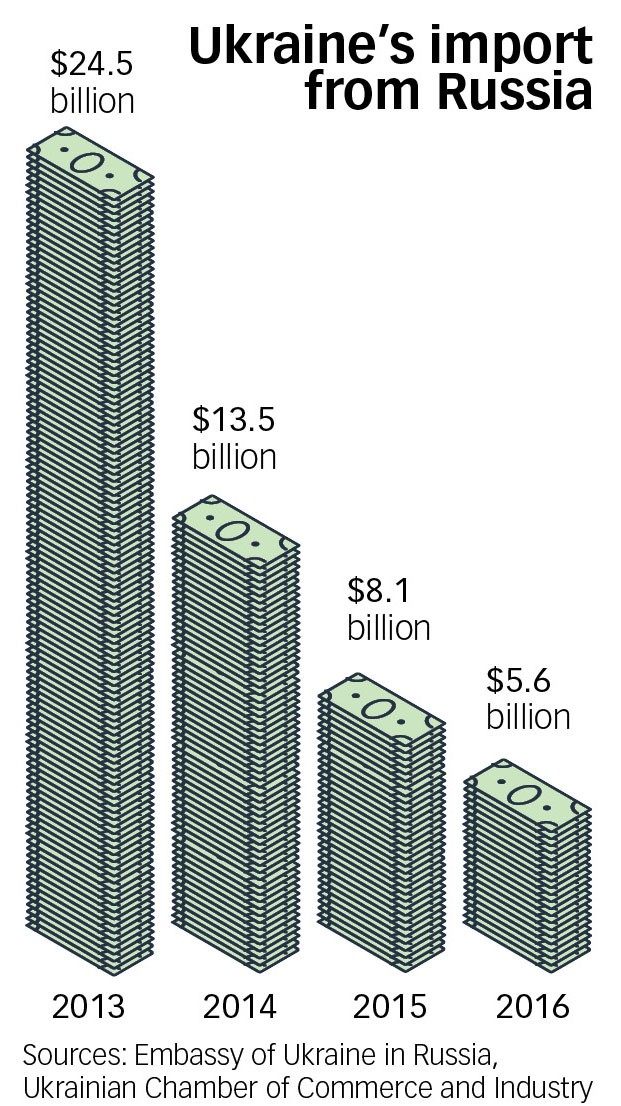

All the same, since the EuroMaidan Revolution that drove Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych to power on Feb. 22, 2014, Ukrainian imports at lot less than it used to – down to $5.6 billion in 2016 from $24.5 billion in 2013, according to Ukrainian Chamber of Commerce President Hennadiy Chyzhykov.

In 2016, Russia mostly bought from Ukraine ferrous metals and metal goods ($893.2 million), nuclear reactors and boilers ($642.9 million), and inorganic chemistry products ($504.9 million).

Chyzhykov said that, since 2014, Ukraine has lost about $14 billion in potential export income because of the fallout from the war and trade embargoes. “Moreover, due to the Russian ban on the transit of Ukrainian goods to other former Soviet bloc and Central Asia countries, we also lost several billion dollars,” Chyzhykov said.

Olga Ponomarenko from the Development Center think tank of the Russian Higher School of Economics said that machinery and heavy equipment always made up the lion’s share of Ukraine’s exports to Russia.

Compared to 2012, exports of these goods fell by 80 percent in 2015.

“Exports of smaller categories of goods fell by ‘only’ 50 percent in dollar equivalent terms, which is an indiation rather of the hryvnia’s devaluation than a significant decrease in real trade volumes,” Ponomarenko told the Kyiv Post.

Russia remains “an important trade partner” for Ukraine, she said, citing the geographical proximity of the countries.

Ukraine and Russia, now at war against each other, are linked by centuries of trade, including in the heavy industrial sector during Soviet times. That bilateral trade dominates despite war.

Banned goods

Back in 2014, when Russia sent its military to invade and annex Crimea and then into the Donbas to ignite the current war, regular Ukrainians were the first ones to call for a shutdown of trade with Russia.

Activists launched a campaign in social media, urging people to stop buying Russian-made goods.

Baskov said he stopped using Russian bank Alfa Bank, and he avoids the Russian-owned chain of fitness centers Sportlife.

“I don’t buy (Russian) chewing gum, chocolate bars or chemical products,” he told the Kyiv Post.

The campaign turned into a wave of protest, with Ukrainian retailers also joining the boycott. Store managers started marking Russian goods with warning signs reading “Made in the Russian Federation.”

In response, Russian President Vladimir Putin ended his country’s free trade agreement with Ukraine in 2015. Ukraine’s cabinet struck back by banning several dozen types of goods from Russia.

Then in January 2016, the Ukrainian and Russian governments extended the mutual embargoes on certain types of goods they initiated in 2015.

Russia banned Ukrainian meat, poultry, fish, vegetables, milk, fruits, and nuts. Ukraine’s list is longer, and includes fish, caviar, poultry, meat, cocoa, sweets, coffee and tea, beer, alcohol, cigarettes, locomotives, and much more. Ukraine has also banned the sale of weapons to Russia, as well as products that can be also used for military purposes.

However, Alexey Doroshenko, a Samopomich Party lawmaker and the head of the Retail Trade Suppliers Association of Ukraine, told the Kyiv Post that the Ukrainian government doesn’t know much about the actual situation on the market.

“They observe the situation from the hills of Pechersk,” Doroshenko said, referring to the fact that most Ukrainian central government buildings are located on the hills of Kyiv’s Pechersk District.

Data published by the State Statistics Service confirm Doroshenko’s claim, revealing that both sides break their own embargoes.

In 2016, Ukraine imported from Russia $306,000 worth of meat and fish, $187,600 worth of coffee and tea, and sugar and confectionaries worth $500,900. Many descriptions of imported and exported goods in the statistics are vague, making it difficult to prove that the embargo was indeed violated.

Russia remained Ukraine’s largest foreign investor in 2016, accounting for nearly 38 percent of the $4.4 billlion total.

Forbidden caviar

One of the goods banned for import from Russia, was one of the nation’s signature products – caviar.

But according to Doroshenko, Ukrainian businesses decided the ban concerned only caviar packed in cans. So they keep importing caviar as a raw material packed in large drums, Doroshenko says, and then repacked into jars for retailing, marking them as “made in Ukraine.”

“You can see how wealthy a country is by checking its exports. The higher the level of processing is, the wealthier the country is. That’s because a product packed in small jars, designed with brand labels, costs a lot more than the same product packed in large cans and sold as a raw material,” Doroshenko said.

In an emailed comment to the Kyiv Post, the press service of Ukraine’s Economic Development and Trade Ministry emphasized the fact that the importation of all Russian caviar has been banned by the government since 2015.

“There is no mention of whether it is packed in Russia or not,” the press service said.

In 2016, Ukraine exported mostly ferrous metals and metal goods to Russia (top) while it bought fossil fuel, oil and petroleum. Both countries did trade involving nuclear reactors and boilers.

Will ‘suffer more’

Kateryna Chepura, spokesperson of the Vidsich Civic Movement that organized the boycott of Russian-made goods in 2014, said the fact that Ukraine and Russian are still main economic partners after three years of war is traumatic.

“Unfortunately, our economies are deeply connected. We understand that and are not calling for an immdiate cut of all the economic ties with Russia as Ukraine will suffer more from that,” said Chepura. “Although our government has been taking measures to decrease our dependence from Russia, the movement is really slow and reluctant. In three years of war they could have done much more than impose the selective list of banned products.”

Baskov is hoping Ukrainian and Russian relations can return to normal — but, for that, Putin would have to go.

“I’m sure that the Russian regime will fall, and we’ll be able to trade with Russia the same as with any other civilized country – on an equal basis, and with competitive market conditions,” he said.

Imports from Russia have dropped significantly since 2013, but remained at $5.6 billion in 2016.

Two reactions to Ukraine-Russia trade amid war

Brian Whitmore,

Senior Russia analyst for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and author of The Power Vertical blog

“This presents a thorny dilemma for Ukraine. For Russia, there isn’t really a distinction between politics and business. The Kremlin has essentially weaponized trade, commerce and finance. The goal is to ensnare elites in the former Soviet Union and beyond in the web of corrupt deals that emanate from Russia and establish a so-called Eurasian business space. I call this a zone of corruption and it is a key tool in establishing a sphere of influence. It is also one of the main reasons the Kremlin was so opposed to Ukraine signing an Association Agreement with the European Union. Given geography, history, and established networks, and Ukraine’s dependence on Russia for things like energy, it will be difficult – but not impossible – for the authorities in Kyiv to escape Moscow’s embrace. An obvious first step would be to really tackle corruption, not just in words but in deeds. Another would be to develop sectors of the economy – like information technology – that can become sources of wealth but are in no way dependent on Moscow. Ukraine and Russia are not just in a war in the traditional military sense. They are also engaged in a war of governance. If Ukraine can prove that a transparent rule-of-law-based system can flourish on its soil it will win the war of governance – and have a stronger hand in the military conflict. If Kyiv fails here, it risks being absorbed by Russia’s zone of corruption.”

Timothy Ash,

London-based analyst with Bluebay Asset Management company

“Since the EuroMaidan (Revolution that ousted Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych on Feb. 22, 2014), and (Russia’s war) in Donbas, there has been a marked decline in trade, energy, and financial ties between Russia and Ukraine. For example, only 4–5 years ago Russia still accounted for around 40 percent of Ukraine’s total trade turnover, which is currently down to around 10 percent, and set to go lower again this year. Meanwhile, whereas five years ago Ukraine was still importing 20 billion cubic meters of gas from Russia – close to half consumption – last year it was close to zero, and overall Ukrainian gas imports have gone down to around 10 billion cubic meters from 40+ billion cubic meters 10 years ago. The recent battle over trade flows to (Kremlin-controlled areas of the Donbas) have also seen Kyiv put additional pressure on the remaining Russian banks operating in Ukraine, which have now been levied with sanctions which are just likely to accelerate their exit. Even in the military field, while the talk is of a frozen conflict in Donbas, the reality is that the Ukrainian economy has learned to live with the status quo, as reflected in the 2.3 percent real gross domestic product growth posted last year, and expectations – pre-blockade of 2.5–3 percent growth this year, and broader macroeconomic stabilization. Any economic leverage which (Kremlin-controlled areas of the Donbas) exerted seems to have been reduced over time – and indeed, Kyiv’s decision now to cut off trade to (separatist areas) suggests a decision to adapt a worse-case scenario, and put the cost of maintaining (separatist areas) onto Moscow directly, as is the case with Crimea, but also Transnistria (in Moldova), Abhazia and South Ossetia (in Georgia).