Since June 2017, the Russian-controlled part of Donetsk Oblast has held journalist Stanislav Aseev in illegal detention for the crime of undercover reporting about the secretive separatists.

But now the Russian-backed militants appear to be actively building an espionage case against Aseev.

Online publications that support the Donbas separatists have posted several texts they claim are excerpts from Aseev’s diary and that depict him working for Ukrainian intelligence, according to Yegor Firsov, a former Ukrainian parliamentarian and friend of the imprisoned journalist.

The separatists are also trying to blackmail Aseev into confirming the information in the diary by threatening to imprison his mother as an accomplice, Firsov wrote, citing unnamed sources.

“As far as I can tell, the militants’ goal is to convince everyone that Stas [Aseev] is not a journalist, but a spy,” Firsov wrote in a Facebook post on July 18. “They want to build the charges and the rest of the court case on this. Specifically because these publications of his ‘diary’ appeared.”

Secret chronicle

A native of Makiivka, a city of 350,000 people located 750 kilometers southeast of Kyiv, Aseev was living in Donetsk in 2014, when a combination of local separatists and Russian forces seized control of much of Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region. While many pro-Ukrainian residents would ultimately flee the region, Aseev stayed put and began chronicling life under the Russian occupation for pro-Kyiv media.

Writing under the pseudonym Stanislav Vasin, he published his dispatches from Donetsk and the surrounding area in news outlets like Ukrainska Pravda, Zerkalo Tizhnya and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

Although he could not conduct interviews or work openly, Aseev’s writings offered one of the clearest windows into the daily life, politics, and the ideology of the Russian-controlled area.

Then, on June 3, 2017, Aseev abruptly disappeared. His friends and family quickly became convinced that he had been arrested by Russian-backed security forces.

Confirmation was slow, but Firsov, Aseev’s family, and journalists were gradually able to discover that he had indeed been detained. Since then, Aseev has been widely believed to face espionage charges.

But movement on his case has been slow. The appearance of the alleged diaries online has led Firsov and others to conclude that the separatist authorities are taking action.

Dodgy diary

In his Facebook post, Firsov says the diaries are fake. They present Aseev “as, at a minimum, James Bond” and contain elements of propaganda, Firsov wrote.

As an argument against their veracity, he published photographs of what he claimed was Aseev’s real diary on Facebook. Firsov wrote that it in his possession.

Firsov did not provide links to the excerpts in question and did not reply to requests for comment.

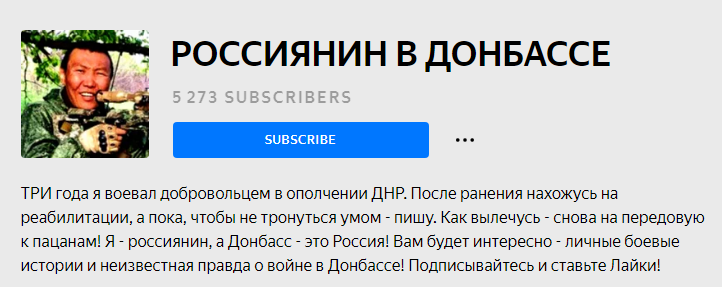

However, the Kyiv Post was able to locate four alleged excerpts from Aseev’s diary in “Rossiyanin v Donbasse” (“A Russian in Donbas”), a channel on the Yandex.Zen platform, which is blocked in Ukraine.

The channel presents its contents as the writings of a Russian who fought for three years in the Donbas before being wounded. Now, according to the channel’s official description, he is writing “personal war stories and the unknown truth about the war in Donbas” to keep his sanity while recuperating.

However, the high number of posts and professional looking content make the channel appear less like a personal blog than a full-fledged media project.

The homepage of “Rossiyanin v Donbasse” (“A Russian in Donbas”), which published questionable texts it claims are excerpts from Stanislav Aseev’s personal diary. The texts suggest Aseev worked for Ukrainian intelligence.

“Rossiyanin v Donbasse” presents the four posts featuring “excerpts from Aseev’s diary” as exclusive publications. “I got the diary from an acquaintance who is a security agent and a former Donbas militiaman,” the channel’s author writes in the intro to the fourth post.

The first post contains rich, even poetic descriptions of Donbas, life inside a warzone, and the author’s emotions about the conflict. Much of it appears realistic.

But it also contains a specific example of propaganda to which Firsov referred on Facebook. In the alleged diary entry, the author describes sitting outside Makiivka and watching a phosphorus bomb fall and explode in the distance.

Both Russian media and state officials have repeatedly accused Ukraine of using white phosphorus munitions in the Donbas. Ukraine, in turn, has at times made similar accusations against Russia and its proxies in the region.

However, a December 2017 post by the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab paints a more complicated picture: “despite the frequent claims, it is difficult to find many — if any — proven, documented examples of the use of the deadly substance in eastern Ukraine over the past three years.”

The next two posts containing Aseev’s alleged diary entries are shorter and less ostentatious. The author describes agreeing to do intelligence work for the Ukrainian Defense Ministry. He then writes of going to investigate a separatist military base and working to form a network of Ukrainian agents in the DNR.

“We encircled the city with a network of informers, after which something would explode somewhere, a Ukrainian flag or inscription would appear somewhere, sometimes someone would disappear,” the author writes.

However, the fourth post returns to the florid literary stylings of the first entry and includes a storyline that strains believability. The author describes falling in love with a woman from a rich family in Western Ukraine.

“For a family of wealthy Carpathian Catholics, I was something like a pygmy with a spear: an impoverished, undeveloped aborigène incapable of understanding the depths of the traditions and saving power of Christ,” he writes.

Ashamed of his poverty, the author begins working for Ukrainian intelligence to earn more money and impress his love interest and her family.

Building a case?

The diary’s story may stretch the imagination, but its descriptions of espionage likely reflect the separatist view of Aseev’s actions.

After his arrest in June 2017, Aseev was subjected to torture and other forms of mistreatment, Amnesty International reported, citing a confidential source.

Since at least late 2017, the journalist has been held at a former factory known as Isolation, one of the harshest informal prisons, according to former prisoners.

On June 28, Aseev launched a hunger strike in protest of mistreatment. He complains that he is kept in a moist cell, is ill, and is not receiving the medicine he needs.

Efforts to free the journalist have proven fruitless — potentially because of the seriousness of the accusations against him. A December 27, 2017 prisoner exchange raised hopes that Aseev might be released. However, he ultimately was not among the 73 captives that the separatists exchanged for 233 prisoners held by the Ukrainian government.

In a March 21 Facebook post, Firsov wrote that he and other supporters of Aseev had tried to use both official and unofficial channels to push for him to be included in a prisoner exchange. But the DNR side “didn’t even want to talk about the possibility of an exchange,” he said.

Beyond the seriousness of espionage charges, one of the reasons may be that Aseev has not yet been tried in the DNR’s unrecognized legal system, says Volodymyr Fomichov, a former political prisoner in the occupied territories who was freed during the December exchange.

Like Firsov, he believes that these alleged diaries are being used to build a case against Aseev.

“It’s all easily explained. The DNR militants need to make an evidence base for their pseudo-judges,” Fomichov told the Kyiv Post. “For this reason, they are falsifying [the diary] and publishing it.”

Under the DNR’s unrecognized legal code, espionage is punished by either 20 years in prison or, if committed during wartime, the death penalty.

“That ruling would be a war crime by the so-called authorities,” says Maria Guryeva, a press officer at Amnesty International Ukraine.

But while the appearance of the “diary” is worrying, few are surprised.

“Actually, they haven’t invented anything new,” Firsov wrote on Facebook. “They accuse every Ukrainian journalist of working with the security services.”