Missing in action: Ruslan Sugak

KHRYSTOPHORIVKA, Ukraine – Ruslan Sugak, 32, a soldier from the Kryvbas territorial defense battalion, went missing on Aug. 29, 2014, during fighting near Ilovaisk, Donetsk Oblast. His name is in Ukraine’s list for prisoner exchanges, but Russian-backed forces in the Donbas have not confirmed that he is in their captivity. Sugak has a wife Maryna, a daughter Nastia, 8, and a son Denys, 6.

Sugak’s mother, Olena Sugak, 53, told her son’s story at her home in the village of Khrystophorivka, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, 400 kilometers from Kyiv. The following is her story, recorded and translated.

Olena Sugak, 53, whose son Ruslan went missing in action in August 2014, stands in the yard of her house in the village of Khrystoforivka in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. (Anastasia Vlasova)

In late April 2014, (Ruslan) was called up to the army. On May 26, the day after the presidential elections, they took the military oath and were sent to the war front.

They were not supposed to be on the frontline — the territorial defense battalion was formed to defend the Kryvy Rih area because there were fears that (Russian dictator Vladimir) Putin might invade here.

Burned by fire

He (Ruslan) told me (his unit) had been based near Zaporizhzhia, and then in Sloviansk and after that Saur Mohyla in Donetsk Oblast.

On Aug. 12, 2014, he came home for three days of leave just before the birthday of his daughter Nastia.

I’ve always wanted my son to be a real man, but not the way it happened.

He was 29 but his eyes were those of an 80-year-old man. I felt like I was speaking to an elderly person. He told me: ‘Mom, the land is burning there.’ We couldn’t understand what he meant.

His friends called him late at night and said he should hurry back as something serious was beginning.

(After his leave was over, Sugak rejoined his unit in the south-east of Donetsk Oblast.)

He was calling me by phone every day. His checkpoint was in Krasnopillia. He said they had captured so many separatists they didn’t know where to keep them.

Together with other moms, we went to the military prosecution in Kryvy Rih demanding that they bring our boys out of that hell. They told us there was talk of a green (evacuation) corridor, and promised that on Monday our sons would be back home.

But Ruslan had no faith in the green corridor. There was hopelessness in his voice. I asked him to save his life by all means.

Then a grim day started. At 7 a. m. I saw medical helicopters heading to Dnipro. Other moms started calling me and I realized that everything was awful.

We were calling to the military commanders, to hotlines, but with no response.

Then the soldiers started returning home to Kryvy Rih, many of them had lost their vehicles. Volunteers and truck drivers were giving them a lift. After Ilovaisk, the Kryvbas battalion took the motto “Burned by Fire.”

Mistake

On Sept. 1, (2014) I was at the funeral of a boy who was serving at the same checkpoint as my Ruslan. I received a call from an aide to Volodymyr Ruban of the Officer Corps. They told us my son was alive, but wounded and in captivity.

Then we were told in the military enlistment office that Ruslan had been released and was on the way home. We rushed to Dnipro, to Ruban’s center. My daughter, daughter-in-law and I were waiting for the released soldier. When these boys arrived they were all scared, black as miners and wearing some scraps of clothes. There had been a mistake. There was another Ruslan among them. We bowed our heads and returned home.

That’s how our sorrows started.

Search

Then I received a call from a boy who told me he had got out of the encirclement together with Ruslan. When they had almost reached Zaporizhzhia Oblast, a safe area, Ruslan stepped on a landmine, so the boy had to leave him and to look for help. When he returned, Ruslan wasn’t there.

Then I received information from our friend that according to some former SBU officers in Snizhne, Ruslan was in a hospital there, and then he was sent to Donetsk.

I sent a request to the police to make them search for him. There was no news from either the police or the SBU. We were doing all the searching by ourselves.

Missing: Galyna and Anatoliy Obruch

Galyna Obruch, 65, and Anatoliy Obruch, 67, retired volunteers, went missing after they traveled on Nov. 12, 2014 from their home in the city of Slavutych in northern Ukraine to eastern Ukraine, with clothes and medication for Ukrainian soldiers. They were reportedly arrested by Russian-backed fighters in the city of Donetsk, but the occupying authorities in control of the city have not confirmed this.

Their story was told by their grandson, Vyacheslav Kryvopalenko, 27, in Kyiv. He has been looking for them since they disappeared. The following are his words, recorded and translated by the Kyiv Post.

Vyacheslav Kryvopalenko shows photos and documents of his grandparents Galyna and Anatoliy Obruch, who went missing in the war zone in November 2014. (Oleg Petrasiuk)

My grandparents were much involved in the EuroMaidan protests — they came there from Slavutych every week. My grandma worked in a kitchen, and my grandpa helped as a Maidan guard.

They worried a lot about the annexation of Crimea. My grandma is Russian by nationality, and she started arguing with her sister Nadya because of all that.

When the war in Donbas started my grandparents vowed to help our soldiers.

They loaded their KIA Cerato car with medicines, warm clothes, blankets, biscuits, pasta and also some homemade canned vegetables and set out on a journey. It was Nov. 10, 2014, when I saw them in Slavutych for the last time.

They told me they would take their stuff to Mariupol, the city where they met each other, and hand it over to local volunteers. I didn’t know then that they had rather different plans.

Last conversation

My grandma called me on Nov. 12, 2014, at about 2 p. m. She told me they were at a Ukrainian checkpoint, that all was fine but she couldn’t talk for long and promised to call me back in the evening.

I called them both at 5 p. m., then at 6 p. m. but without any response. Then me, my aunt and my sister were calling them for the next three days, every 20 minutes. Then we reported them as missing to the police and the SBU security service.

It was only in June 2015, when the police gave us a printout of their phone conversations, (that I found out) that my grandma had actually called me on Nov. 12 from the city of Donetsk, on Hurova Ave. They arrived there in the morning, the mobile signal records showed.

Apart from calls to family members, they called two unknown phone numbers. I called them and found out the real story.

Risky trip

My grandparents had decided to help some soldiers from Slavutych that were fighting in Pisky, near Donetsk airport.

They contacted a man in Donetsk called Serhiy and asked him to guide them to Pisky. When they met up, Serhiy told them it was too dangerous and tried to guide them out of the (Russian-occupied) city. And on the way out, on Hurova Ave., he told me they were arrested by the Oplot battalion.

They saw a license plate of a car issued in Kyiv, and my grandparents also had a Ukrainian flag in their car. Serhiy said they were accused of being the spotters for Ukrainian army. My grandma tried to calm them down, telling them she was ethnic Russian herself.

The fighters took Serhiy to jail and handed over my grandparents to the MGB (the Russian occupation authorities’ security service.) Serhiy told me he spent one month in prison before being released. He didn’t know what had happened to my grandparents.

I called him back in a year, early in 2016. I tried to make him understand our grief. In May 2016, during our last conversation he told me: “You don’t need to look for them. They are no longer alive.” He didn’t explain to me what happened.

No search

There were four changes in the police detectives in charge of this case over the years. I wanted to complain about the police and prosecution, but they even didn’t show me the criminal case regarding the search for my grandparents.

Instead, there were more than 20 cases of fraudsters demanding money from me for information about my grandparents. I gave information about those fraudsters to the police and SBU. But the police found nothing.

In the winter of 2015, I filed a lawsuit with the European Court of Human Rights, complaining that Ukraine’s law enforcement bodies weren’t searching for them.

Uncertainty

My grandparents went to Slavutych after the Chornobyl catastrophe and worked at the nuclear power plant. Just like my grandfather, I’m an atomic electric engineer.

I want to have some clarity on what happened to them. If they’re alive, then I want to be able to get them back. If not, then I want at least there to be a grave to visit.

This uncertainty is painful. I even try not to go to Slavutych, because I may accidentally pass by their windows and start remembering them.

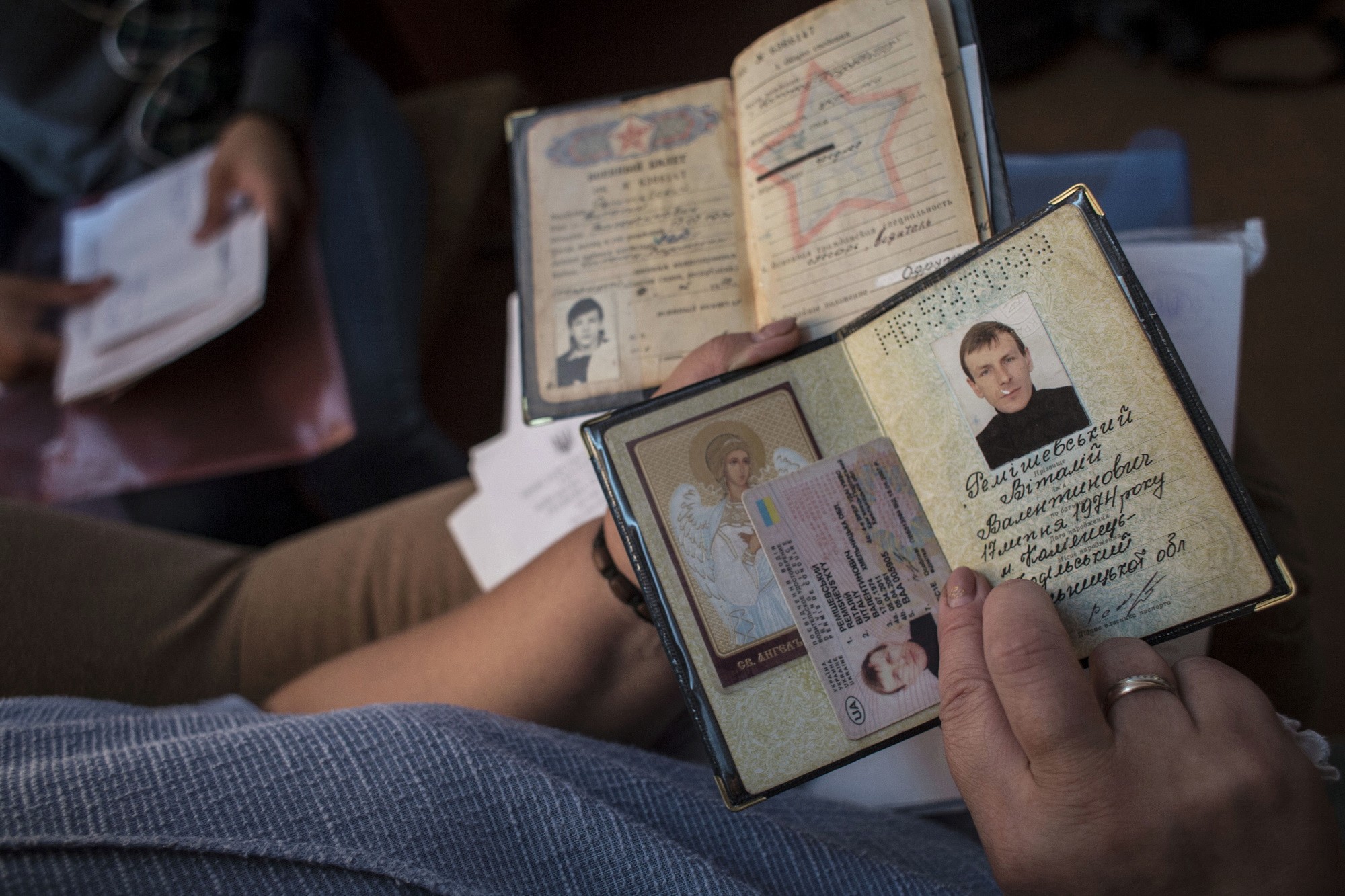

Missing in action: Vitaliy Remishevsky

HOLOSKIV, Ukraine — Vitaliy Remishevsky, 42, a soldier of the 95th brigade, went missing on Jan. 20, 2015, in the village of Pisky near Donetsk airport. He is listed as killed by Wikipedia and in the Memory Book, an unofficial database of killed soldiers. But his family won’t acknowledge his death without receiving back his remain, or getting exact details about his fate. Remishevsky has a wife and three children – Roman, 25, Maksym 20, and Daryna, 13.

Remishevsky’s story was told by his wife Oksana Remishevska, 45, at their house in the village of Holoskiv in Khmelnytsky Oblast in western Ukraine. Remishevska recently developed problems with her thyroid gland and eye problems due to stress.

Oksana Remishevska shows the papers of her husband Vitaliy, who went missing in action in 2015. (Anastasia Vlasova)

My husband participated in UN peacekeeping missions in Lebanon in 2000 and in Iraq in 2004. If anything had happened to him there, I would have got explanations much more easily than now in Ukraine.

Vitaliy was called up by the army on April 1, 2014. He didn’t tell me why it happened so quickly, but I believe he volunteered to go there. He was much inspired by the EuroMaidan protests.

He told me he would serve as a military driver in Zhytomyr, in the 95th airborne brigade. Only later I found out from the Ministry of Defense that he had fought in Dobropillia, Sloviansk, Kramatorsk and in Pisky.

He came back home in summer 2014 after spending some time at a military hospital with pneumonia. He didn’t tell me much about the war, but said the commanders were taking all of the sleeping bags for themselves, while the ordinary soldiers had to sleep on the damp ground, and he argued with them because of that.

I saw Vitaliy become more reserved and nervous, he was glued to the news on TV.

He returned to the war zone in January 2015, initially to Zhytomyr then to Sloviansk, where he was based in an abandoned kindergarten with the soldiers of 95th brigade.

Last phone call

On Jan. 18, he called me and said his bus had broken down, and he was staying with the guys in a field, without telling me where exactly. He said it was dirty and he was wearing Soviet rubber boots. I later found out that it was near Pisky.

Then he called me on Jan. 19, it was Epiphany and he was pleased to know that we went to a church in Kamyanets Podilsky, at the place where he had spent his childhood. He sounded very joyful and said to me: ‘I love you.’ But unlike usual he didn’t say goodbye to us.

On Jan. 20, at 11:30 his fellow solider, with the nickname Svat, called me and said that Vitaliy had been killed. I told him I didn’t believe him.

No explanation

We started calling morgues, to volunteers who were helping the army, searching on the internet. I found that my husband had left near our (religious) icons some useful phone numbers of his comrades, and I started calling them.

When I eventually spoke by phone with his commander and asked where Vitaliy’s body was, he told me that my husband had been blown up into small pieces and there was nothing to pick up.

But on Jan. 22, our elder son found a video on You Tube in which the separatists were showing Vitaliy’s IDs and said the Ukrainian army had left behind one of its soldiers.

Then I saw that Vitaliy’s cell phone had become active again. I called it and some unknown man answered. I asked to be allowed to talk to my husband, and the man told me to come to Donetsk and see him there.

I was talking to the man for about a week. He initially demanded a ransom for my husband, but in the end, he told me angrily to keep this money for my children.

Search

I went to the SBU (state security service) to ask them to track my husband’s phone. I called his commander again, wondering if he really knew what had happened. He answered that he didn’t know.

The army initially wrote to me that Vitaliy had been killed, but later they started calling him missing.

I spoke to several soldiers, who participated in the fighting. Some of them said that Vitaliy was picking up the wounded, or that a shell directly hit him, or that he was killed by a sniper. None of them agreed to talk to me face to face. Many of them were later killed in action.

My son submitted samples for a DNA test, but they didn’t match any of the recovered dead bodies.

In January 2016, we received an envelope from Kyiv with Vitaliy’s driver’s license, military ID and his ID as a participant of the anti-terrorist operation (Ukraine’s official name of the military campaign.) All of his papers were clean, without any blood.

This envelope had the marking of Military Unit E6100, which belongs to the SBU.

Hard to let go

Some lawyers told me that I have to recognize that he has been killed, that I would get a state pension for him. Now I can’t even send my daughter Daryna abroad because she needs the permission of her father for this. But we think we will let Daryna travel around Ukraine for now.

My children, my love for my husband and my faith keep me going. We believe he’s alive and we light candles for him in church.

It’s hard to let go of a person. How can I bury a person when I’ve not seen that they have died? I cannot get over it.

Read the main story about the people missing at war here