Editor’s Note: This is the fifth installment in the Kyiv Post’s “Honest History” project, a series that debunks myths about Ukrainian history used by propagandists. The stories and videos are supported by the Black Sea Trust, a project of the German Marshall Fund of the United States. Opinions expressed do not necessarily represent those of the Black Sea Trust, the German Marshall Fund or its partners.

Russia has for centuries promoted the myth that the Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians are one people, or nation, centered in Moscow.

The theory has been used to entrench Russian imperialism and undermine the Ukrainian and Belarusian national identities. It has also been used as an ideological weapon in Russia’s military aggression against Ukraine since 2014.

However, the theory of the tripartite people, on closer examination, appears to be an ideological paradigm that has little to do with actual fact.

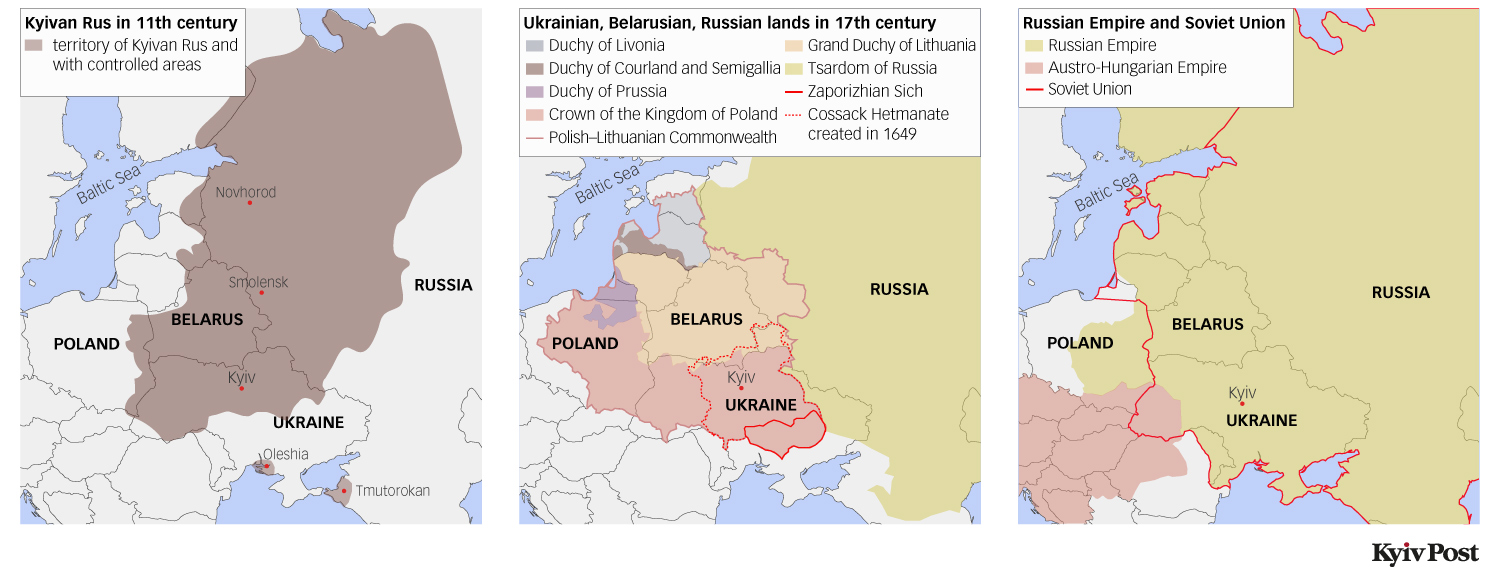

After the collapse of Kyivan Rus, which included parts of modern-day Ukraine, Belarus and Russia, various names for these three countries emerged in the 14th to 17th centuries. Their borders ebbed and flowed with the rising and falling of states and empires.

In fact, before the 18th and 19th centuries, Russia, Belarus and Ukraine did not exist in the form of the nations that we know now. And despite Russia’s efforts, there has never been a long-lasting project to unite the three entities into one nation.

This is because, before the era of nation states, Europeans’ identity was a complex mix of allegiance to tribes, religions, cities, geographic areas, monarchs and medieval trading guilds. Speaking about a “single Russian people” after the collapse of Kyivan Rus and its splintering into separate principalities, which in turn evolved into separate countries, is thus nonsensical.

Kyivan Rus

The medieval state of Kyivan Rus, centered in Kyiv, emerged in the 9th century. Its residents shared a common ruling dynasty, the Scandinavian Rurikids, standard literary languages – Old Ruthenian and Church Slavonic – and Orthodox Christianity.

In the 12th to 13th centuries Kyivan Rus split into separate principalities, and in the 14th to 15th centuries its southwestern part became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, while its northeastern part was conquered by the Grand Duchy of Moscow.

Two separate literary traditions emerged – one in Russian (in the Grand Duchy of Moscow) and one in Ruthenian (also known as Old Ukrainian and Old Belarusian), which was initially the standard and dominant language in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Geographic names

The word “Little Russia” (Malaya Rus) emerged in the 14th century as a Byzantine church term for the kingdom of Galicia-Volhynia. It was later applied to other territories that are now parts of modern Ukraine.

After northern Ukraine became part of the Polish realm in 1569, and after Cossack leader Bodhan Khmelnytsky established the Hetmanate state in central Ukraine in 1649, the name of Ukraine started to be used as a country name for the entire area from Lviv to Putivl in modern-day Sumy Oblast, according to Kyrylo Halushko, a historian at the History Institute of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences. What is now southern Ukraine was at that time part of the Crimean Khanate, a successor of the Golden Horde and a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire.

The name “Ukraine” (meaning “borderlands”) had first been used in 1187 in the Hypatian Codex to identify the southern borderlands of Kyivan Rus. However, at that time the name had been used in manuscripts to identify not a specific geographic area but any borderlands of Rus.

The Belarusian-speaking residents, along with Lithuanian-speaking ones, of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were referred to as Litvins (Lithuanians) starting from the 14th century, and this name was a major self-identification of Belarusians until the 19th century. The name “White Russia” (Belarus) started to be used for what is now the state of Belarus in the 16th to 17th centuries.

The Grand Duchy (and later tsardom) of Moscow began to be referred to as Russia (from the Greek “Rossia”) or Great Russia (Velikaya Rus, Velikorossia) in the 14th century. In Europe, it was known as Muscovy.

Parts of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia were part of Kyivan Rus. These countries emerged as separate geographic entities in the 14th century and as modern nations in the 19th century.

Imperial myth

After Russia annexed eastern Ukraine as part of the 1654 Treaty of Pereyaslav, it began to develop the theory that there was a unified “Russian” people, based on common Kyivan Rus legacy and Christian Orthodoxy, and centered in Moscow. The term “Ruthenian” (Rusyn) had been used by both the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Muscovy to refer to Orthodox speakers of East Slavic languages, along with other ethnic and religious terms.

Innocent Giesel, head of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, formulated the theory of the tripartite “Slavic Russian people” in his 1674 Synopsis.

Theophan Prokopovich, a rector of the Kyiv Mohyla Academy and the de facto head of the Russian Orthodox Church in the early 18th century, was also an author of a theory of the unity of the “Great Russian, Little Russian and White Russian (Belarusian)” people.

But portraying the successors of Kyivan Rus as one unified people is as non-scientific and absurd as doing the same with the Carolingian Empire, which included France, Germany and parts of Italy, Yaroslav Hrytsak, a professor at the Ukrainian Catholic University, told the Kyiv Post. It is a mythological concept that has little to do with science, he said.

Galician Russophiles

In the first half of the 19th century a Russophile movement emerged even outside the Russian Empire – in Galicia, Transcarpathia and Bukovyna, which were parts of the Austrian and then Austro-Hungarian Empire.

But when the Russian Empire occupied Galicia in 1914 to 1915 during World War I, it attempted to impose the Russian language and culture and the Russian Orthodox Church in such a heavy-handed manner that these efforts encountered opposition even from within Russia itself.

Russian ex-Interior Minister Pyotr Durnovo was an opponent of annexing Galicia, saying that its residents had lost their connection to Russia. He also said that a potential annexation of Galicia would drastically increase the number of Ukrainian nationalists in the Russian Empire, and undermine it.

Russian liberal Pavel Milyukov also criticized Russia’s russification policy in Galicia as a “European scandal.”

After Russia lost Galicia to Austria-Hungary again in 1915, Russia’s Galician Governor General Georgy Bobrinsky’s staff issued a review that concluded that the Russification efforts had been too quick and too brutal.

Meanwhile, Austro-Hungarian authorities imprisoned some prominent Russophiles in Western Ukraine, charging them with spying for Russia, and executed some of them.

In Galicia, the Russophile movement waned and was completely eclipsed by the Ukrainian national movement during World War I. However, in Transcarpathia and Bukovyna Russophiles remained strong until they became part of the Soviet Union in the 1940s. As a result, some residents of Ukraine’s Zakarpattia Oblast still self-identify as Ruthenians, as opposed to Ukrainians.

Post-1917 concepts

The Russian imperial concept of the tripartite nation was discarded by the Bolsheviks in 1917. They emphasized the separate Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian nations as part of the Soviet Union.

However, in the 1930s Joseph Stalin partially reversed the Soviet support for national movements, reverting to pre-1917 imperialism.

Later the official ideology developed the concept of the single “Soviet people” – a concept similar to the Russian Empire myth.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the identities of the separate Russian, Belarusian and Ukrainian nations were fully entrenched in the newly created states of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

However, the pre-1917 theory of the tripartite Russian nation was soon resurrected by some Russian imperialists. These include Alexander Dugin, the founder of Eurasianism; the eccentric polymath Anatoly Vasserman, the Stalinist Alexander Prokhanov, and Igor Strelkov, a Russian warlord who launched the invasion of the Donbas in April 2014.

This old-fashioned theory has been a major ideological weapon used by Russia during its aggression against Ukraine.

Russia’s claims to Crimea and the Donbas were partially based on the myth that they were part of a “greater Russia.” More radical proponents of this theory went even further, saying that Russia should annex southeastern Ukraine from Odesa to Kharkiv, or even the whole of Ukraine.

Nation or people?

Much confusion in the identification of the Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian peoples comes from the common misunderstanding about the difference between the concepts of “people, or ethnicity” and “nation.”

Ethnicities have a much longer history. Members of an ethnicity, or a people, identify with each other based on common ancestry, language, history, society and culture.

Modern nation states, however, emerged only in the 18th to 19th centuries as replacements for feudal systems, with popular sovereignty replacing allegiance to monarchs.

Although nations also often share a common language, history and culture, it is not their defining characteristic. Modern nations are based more on a sense of political and civic unity.

“All nations are modern and contemporary,” Hrytsak said. “Neither Russia, nor Ukraine nor Belarus met the criteria of a nation before the 19th century. They emerged predominantly in the 19th century, but each of them claims to have an old history.”

This misunderstanding may be behind Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s failure to seize the whole of southeastern Ukraine from Odesa to Kharkiv in 2014. Assuming that the residents of those regions speak Russian and share some religious and cultural legacy with Russia, the Kremlin failed to realize that they still consider themselves part of a separate civic nation.

Moreover, even many ethnic Russians living in Ukraine have vehemently opposed Russian aggression and helped or fought for the Ukrainian military because they deem themselves to be part of the Ukrainian nation.

The irony is that the Russian nation was the slowest of the three to emerge because “empires are hostile to nations and are afraid of nationalism,” Hrytsak said.

Ukrainian identity

Ukraine’s national identity in the modern sense of the word started emerging simultaneously with those of other European nations in the 18th to 19th centuries, although its development was initially thwarted by the absence of a Ukrainian state.

The modern Ukrainian literary language, in contrast with old Ukrainian (Ruthenian), was first used by writer Ivan Kotlyarevsky in his Aeneid in 1798.

The nineteenth century marked the flourishing of classical Ukrainian literature, with its three pillars being Taras Shevchenko, Lesya Ukrainka and Ivan Franko.

In 1845, the Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius was co-founded by Shevchenko. The secret political society advocated Ukrainian national rebirth and was suppressed by the Russian imperial authorities.

The first Ukrainian nationalist parties emerged in the Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empires in the late 19th century.

Statehood

As a result of the Russian Empire’s collapse Ukrainian nationhood reached the next level by founding its own short-lived states: the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1917 to 1921) and the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (1918 to 1919). However, they were conquered by Soviet Russia and Poland, respectively.

In 1926 Lviv-based Dmytro Dontsov published his Nationalism magnum opus, founding the mainstream version of Ukrainian nationalism – integral nationalism.

This movement was further developed by the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), founded in 1929. In 1940 it split into Stepan Bandera’s OUN and Andriy Melnyk’s OUN.

Ukraine’s national identity then advanced when the nation restored its own statehood in 1991 and when the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution further severed ties to imperial Russian and Soviet legacy.

And Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which started in February 2014, while threatening the state’s territorial integrity, has also, ironically, accelerated the strengthening of Ukraine’s national identity.

See these sidebars to the story

Russia suppressed Ukrainian identity for centuries

The Russian Empire sought to stamp out the Ukrainian identity by cracking down on the Ukrainian language and culture.

Ukrainian was banned in 1804 as a subject and a language of instruction in schools.

The Kyiv Mohyla Academy, the most prominent center of Ukrainian culture, was closed in 1811.

In 1847, Ukrainian writer Taras Shevchenko and other members of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, a secret pro-Ukrainian political society, were arrested. Shevchenko was exiled and later imprisoned for six years.

Russian Interior Minister Pyotr Valuyev proclaimed in 1863 that “there never has been, is not and never can be a separate Little Russian language.”

In 1876, Emperor Alexander II issued the Ems Ukaz, an edict banning the publication and importation of most Ukrainian-language books, public performances and lectures.

In contrast with the Russian Empire, the leadership of Austria-Hungary allowed Ukraine’s culture and language to develop and thrive. That is one of the reasons why Galicia became “Ukraine’s Piedmont” – the birthplace of Ukrainian nationalism – a reference to the Kingdom of Sardinia in Italy’s Piedmont and Sardinia provinces, which unified Italy in 1861.

False arguments behind ‘one people’ myth

Russia has used different arguments to prop up its theory that Russians, Ukrainians and Belarusians are one people.

Russian imperialists’ theory that they are one people because the Russian language is widely used in all three countries does not stand up to scrutiny.

First, there are many nations and peoples that share a language but are still separate. One example is Americans, Canadians, Irish, Scots, English, Welsh, Australians and New Zealanders, all of whom speak English.

Second, there are nations that use several languages simultaneously (just like Ukraine uses both Ukrainian and Russian). In Switzerland, the national languages are German, Italian, French and Romansh.

Religious unity (the prevalence of Orthodox Christianity in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus) is an even weaker argument. There are numerous nations and peoples that share the same religion but remain separate.

Another imperialist argument is based on the fact that all three nations stem from Kyivan Rus. But the fact that Kazakhs, Tatars and many other peoples stem from the Golden Horde does not make them one people. Another example: most residents of Mediterranean states are not one nation, despite their ancestors having once lived under the Roman Empire.