SUMY, Ukraine – Volodymyr Nykonenko and Ihor Hannenko never thought they would have to sacrifice their freedom for their political views.

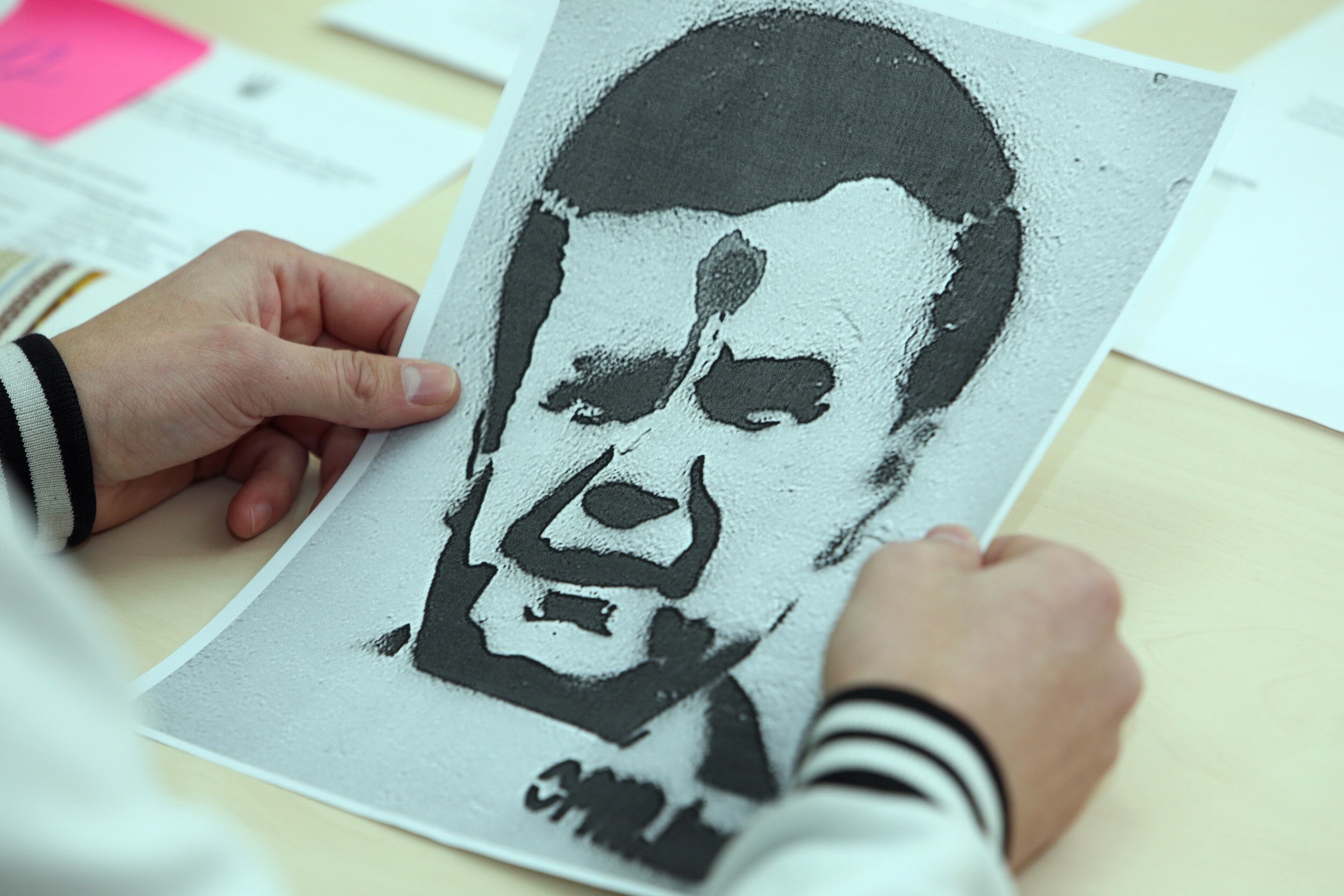

Back in 2013, they were found guilty of drawing street art depicting then-President Viktor Yanukovych with a gunshot wound to the head in their native Sumy, a city of 269,000 people some 330 kilometers northeast of Kyiv.

The images, which they drew with stencils, were deemed extremist. Nykonenko, who was 24 at that time, and Hannenko, who had just turned 20, were sentenced to one year and 20 months in prison respectively. Four years later, Yanukovych has been gone for three years, ousted by the EuroMaidan Revolution in early 2014, and Nykonenko and Hannenko have gone from being convicts to local politicians. Today, they hold seats on the regional and city councils in Sumy.

‘Sumy artists’

But when Nykonenko and Hannenko drew their risky street art in 2011, they were very far from thinking about careers in politics. The image wasn’t even theirs: They made their stencil from an image found on the internet.

The images of Yanukovych with a gunshot wound started appearing on walls in various cities as a reaction to his winning the presidential race in 2010.

“When the graffiti appeared it was a shock for the system,” Nykonenko, now 29, says.

Sumy was one of the Yanukovych’s political strongholds, and drawing the offensive image there was especially risky. Still, Nykonenko and Hannenko, two students and strong opponents of Yanukovych’s pro-Russian politics, went for it. At night they used a stencil to draw about 30 images on the main street of Sumy.

But early in the morning there was no sign of the pictures. All had been removed.

Volodymyr Nykonenko shows an image they drew with stencils back in 2011.

They two didn’t think they were doing anything illegal: After all, Hannenko recalls, the image was all over the internet anyway.

But soon the authorities came for them. At first, they were just interrogated. They didn’t deny being responsible for the graffiti. Then both were detained.

Hannenko, then 18, was arrested on a bus on his way to classes. Two men rushed into the bus and pulled him out. They didn’t bother showing their IDs. The other passengers didn’t try to intervene. On the same day, the police searched his apartment, taking his computer, college notebooks, and a flag of Ukraine that he owned.

Hannenko, present during the search, was terrified that the police would plant some fake evidence that would hurt his family. Desperate to stop the search, he slit his wrist.

“I can’t explain now why I did that. I was 18 and scared,” he says. “I thought maybe they would call an ambulance and the search would be over. Instead, they called me an idiot and kept checking every single item in the apartment.”

Jailed

Their case, dubbed “Sumy artists,” went through many court hearings in 2012.

“It was rather difficult to send someone to prison just for the stencils,” Nykonenko recalls.

Finally, in early 2013, the two were sentenced to prison for hooliganism under “aggravated circumstances.” Hannenko was additionally charged with an attempted arson attack on a local hostel – an action he denies. Their appeals against their convictions were refused.

The two went to different jails. Hannenko spent three months in a detention center before being moved to Byshkivska prison in Poltava Oblast. Nykonenko was transferred to a minimum security prison in Sumy Oblast’s Konotop.

Nykonenko was lucky: He was allowed to go out on weekends and even travel to Kyiv to take his college exams. Hannenko had a regular prison experience.

But both of the “Sumy artists” recall the prison as a “different world” with its own jargon, hierarchy and rules, and say that jail doesn’t help to reduce the number of crimes, but instead breeds even more offenders.

“I wasn’t scared (of prison), but I had no interest in learning more about that world,” Nykonenko recalls. “I worked, exercised and slept enough. Sometimes you can even get healthier in prison.”

Nykonenko was released on parole after eight months in prison in November 2013. Days after, the EuroMaidan Revolution started, and he rushed to Kyiv.

“I knew I couldn’t get caught on Maidan (by police), because I would go back to prison. I never threw a single Molotov cocktail,” Nykonenko recalls.

Hannenko wasn’t that lucky: He watched the revolution from prison. Friends would call him right from the Maidan to brief him on the news.

When Yanukovych fled on Feb. 22, 2014, Hannenko was declared to have been a political prisoner and was soon released.

Volodymyr Nykonenko (L) and Ihor Hannenko talk to the Kyiv Post on April 1.

From prison to war

Soon after the two got out of prison, the war in the Donbas started. Nykonenko quickly volunteered to fight. Having little trust in the regular army, he joined the battalion of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN).

In early 2015, he witnessed the fall of Donetsk Airport, after a 242-day siege by Russian-separatist forces. Soon, he had to go home: His wife was pregnant and wanted him to end his service.

“She waited for me when I was in prison and I didn’t want to make her life any harder,” Nykonenko says. Now they are raising their 2-year-old son together.

Like many veterans, Nykonenko struggled to readjust to life after serving in the Donbas. But one thing he couldn’t stay away from was, surprisingly, politics.

Together with Hannenko, he decided to participate in the local election in the autumn of 2015. They were offered to run on Batkivshchyna party ticket.

“We did everything ourselves, including giving out leaflets on the streets,” Hannenko says.

Nykonenko was elected to the city council and is now in charge of a municipal architecture company. Hannenko took a seat on the Sumy Oblast council.

Six years after they sneaked out at night to decorate their city with risky graffiti, the ex-cons are spending their days quite differently. Nykonenko works on building the first bikeway in the Sumy city center and a skate park. He fought to win the funds to build them.

“We used to be on the other side of the barricades, we were activists,” he says. “Now that we’re in power, it’s a different story.”